Knowledge of Mexico’s history before the Spanish conquest comes primarily from the analysis of Mesoamerican indigenous manuscripts (especially Aztec, Mayan, and Mixtec codices) by archaeologists, epigraphers, and ethnohistorians. Accounts from Spanish conquistadores and post-conquest Indigenous chroniclers are the main sources for understanding Mexico at the time of the Spanish arrival.

Pre-Columbian Civilizations

There is a lot of debate as to when the first humans began to settle in Mexico. For most of the 20th century archeologists estimated the arrival of humans to North America at around 13,000 BCE. Recent discoveries at a cave in the northof Mexico, the Chiquihuite Cave have prompted a reevaluation of the timeline for the earliest human habitation of the Americas. Stone tools and other artifacts unearthed there provide evidence of human presence in central Mexico around 30,000 years ago, indicating settlement significantly before the Last Glacial Maximum.

These first inhabitants were nomad hunters and took refuge in caves.

1500 BCE The Olmecs

The Olmecs, the first major civilization in Mesoamerica (c. 1500-400 BCE), are known for their colossal stone heads, sophisticated art, and influence on later cultures like the Maya and Aztec. They flourished in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico.

Seventeen confirmed colossal heads have been discovered to date ranging in height from 1.17 to 3.4 meters (3.8 to 11.2 feet) and weighing between 6 and 50 tons.

The exact meaning of the colossal heads is still debated, but the most widely accepted theories include that they may be portraits of Rulers and that their placement may be Markers of Rulership and Political Power.

2000 BCE – 1500 CE The Maya

The Mayan civilization was a complex and highly developed society that flourished in Mesoamerica (present-day southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador) for thousands of years.

The Maya civilization was characterized by numerous independent city-states. These were not just simple towns, but rather complex urban centers that served as political, religious, and economic hubs. Each city-state had its own ruling dynasty, its own administrative structures, and often its own patron deities and distinct artistic styles, although they shared a common cultural foundation.

Kmusser.

Preclassic Period (c. 2000 BCE – 250 CE): The early development of Mayan society, with the rise of agriculture and the first villages and ceremonial centers.

Classic Period (c. 250 CE – 900 CE): Considered the golden age, marked by the construction of large urban centers, monumental architecture (pyramids, temples, palaces), advancements in art, writing, astronomy, and mathematics. Prominent city-states like Tikal, Palenque, Copán, and Calakmul thrived.

Postclassic Period (c. 900 CE – 1500s CE): A period of change and upheaval, with a shift of power northward to the Yucatán Peninsula. Important centers included Chichén Itzá, Uxmal, and Mayapán. The civilization was in decline by the time the Spanish arrived.

Temple I, at Tikal, was a funerary temple in honour of king Jasaw Chan Kʼawiil I:

Hochob, Campeche, Mexico: building II, central part:

The Maya developed a hieroglyphic writing system, one of the most complex in Mesoamerica, used to record history, astronomy, and religious beliefs in codices (books) and on stone monuments.

The Maya hieroglyphic writing system, visually stunning and remarkably complex, employed hundreds (estimated at around 800) of unique glyphs representing humans, animals, the supernatural, objects, and abstract designs. These glyphs served as either logograms conveying meaning or sylabograms indicating sound, allowing the Maya to transcribe their language fully, capturing any spoken word, phrase, or sentence.

Here are some of their logograms:

If you are interested in the Maya writing system, check out this WEBSITE. It is very complete and understandable.

800 BCE – 1000 CE The Toltecs

The Toltec civilization was a pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that dominated central Mexico from the 10th to the 12th centuries CE. Their capital city was Tollan-Xicocotitlan, near the modern city of Tula de Allende in the state of Hidalgo. The name “Toltec” itself, derived from Nahuatl, means “craftsman” or “artist,” reflecting the high regard in which later cultures, particularly the Aztecs, held their artistic and intellectual achievements.

The Toltecs had a recorded history that combined epic narratives and historical accounts, often focusing on rulers like Mixcóatl and his son Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. The reign of Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl is particularly significant, as he is associated with the introduction of the cult of Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent) and a period of prosperity in Tollan. However, legends also tell of his exile or departure from Tula.

The Toltecs had a significant influence on later Mesoamerican cultures, particularly the Maya and the Aztecs.

The Aztecs held the Toltecs in high esteem, viewing them as their cultural and intellectual predecessors. They adopted many aspects of Toltec culture, including religious beliefs (like the veneration of Quetzalcoatl), artistic styles, and origin myths. Aztec rulers often claimed Toltec ancestry to legitimize their power. The term “Toltec” in Nahuatl even came to mean “artisan,” highlighting the Aztec admiration for their craftsmanship.

1325 CE –1521 CE The Aztecs

The Aztecs, also known as the Mexica, were one of several Nahuatl-speaking groups that migrated into the Valley of Mexico after the decline of the Toltec civilization. According to their legends, they originated from a mythical place called Aztlán.

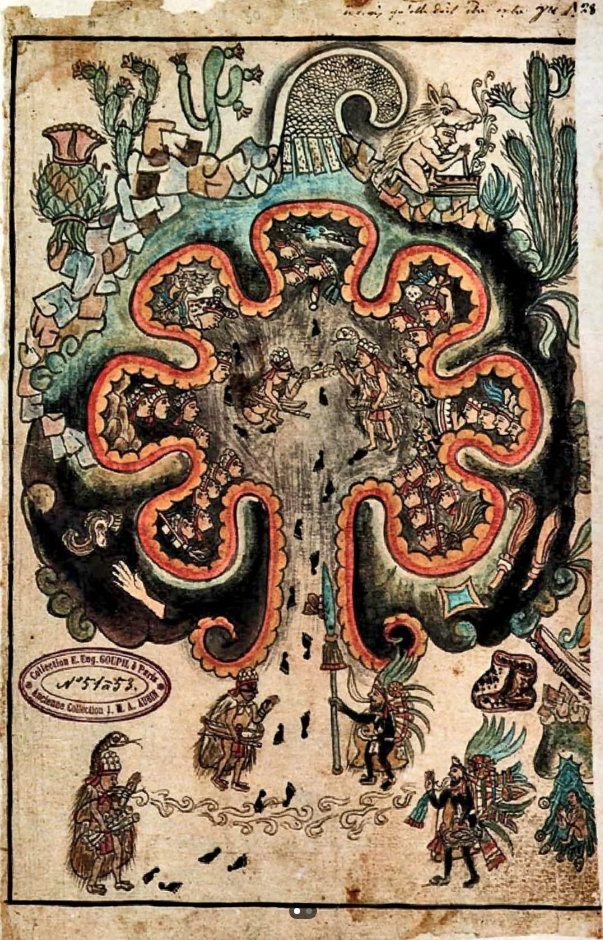

Nahuatl historical accounts tell of seven distinct tribes residing in Chicomoztoc, meaning “the place of the seven caves.” Each cave corresponded to a specific Nahua group: the Xochimilca, Tlahuica, Acolhua, Tlaxcalteca, Tepaneca, Chalca, and Mexica. Additionally, the Olmec-Xicalanca and Xaltocamecas are also reported to have originated from Aztlan. United by their shared linguistic roots, these groups are collectively known as the “Nahualteca” (Nahua people). These tribes eventually departed the caves and established settlements in the vicinity of Aztlán.

Guided by their patron god Huitzilopochtli, they eventually settled on islands in Lake Texcoco. In 1325 CE, they founded their capital city, Tenochtitlán, which grew to become one of the largest and most impressive cities in the world at the time.

Through strategic alliances, particularly the Triple Alliance formed in 1428 with Texcoco and Tlacopan, the Aztecs expanded their power and began to dominate the Valley of Mexico and beyond. Their empire was not a centralized territorial empire but rather a system of tribute and alliances, where conquered city-states were required to pay tribute to Tenochtitlán.

Initially, the Aztecs were subordinate to other more powerful groups in the Valley of Mexico. Through strategic alliances and military prowess, particularly the formation of the Triple Alliance with Texcoco and Tlacopan in 1427, they defeated their rivals and began a period of rapid expansion. Tenochtitlan became the dominant power in this alliance, and the Aztec Empire eventually controlled a vast territory stretching across much of central Mexico, from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts and as far south as Guatemala. Their rule was maintained through a combination of military conquest, political alliances, and a system of tribute from conquered city-states.

Aztec society was highly stratified, with a clear division between the nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin).

Agriculture was the backbone of their economy, with innovative techniques like chinampas (floating gardens) significantly increasing food production. Maize, beans, and squash were staple crops. The following video showcases how the Aztecs developed an incredible system that not only nurtured them but their land as well.

They were skilled artisans, producing intricate works in gold, silver, obsidian, and feathers. Their architecture was monumental, featuring impressive temples, pyramids, and palaces.

The Aztecs had a complex calendar system, including a 365-day solar calendar and a 260-day ritual calendar, which were deeply intertwined with their religious practices. They had a form of writing that used logograms and syllabic signs, and they produced codices (books) that recorded their history, religion, and other aspects of their culture.

1502 Montezuma Xocoyotzin becomes the ninth Tlatoani or ruler of the Aztec Empire. During his reign, Montezuma II expanded the Aztec Empire to its greatest size, extending its influence from central Mexico down to parts of what is now Honduras and Nicaragua. He was known for his administrative skills, dividing the empire into 38 provinces to centralize control and ensure the collection of tribute. He also continued the Aztec tradition of warfare and religious observance, with increased rituals and sacrifices.

SPANISH CONQUEST / NEW SPAIN

1521 – 1821

The Aztecs believed that according to a prophecy, their god Quetzalcoatl would return one day as a human by sea. When the Aztecs saw the Spanish ships and Hernan Cortez arrive in 1519 CE, they thought he was Quetzalcoatl and this marked the beginning of the end of the Aztec Empire.

1521 The Spaniards led by Hernan Cortez gain control of the Aztec Empire because of their weapons, the tactical destruction of key components of their civilization including their leader Montezuma and the spread of diseases that the indigenous people were not immune to (and had no way to protect themselves from them).

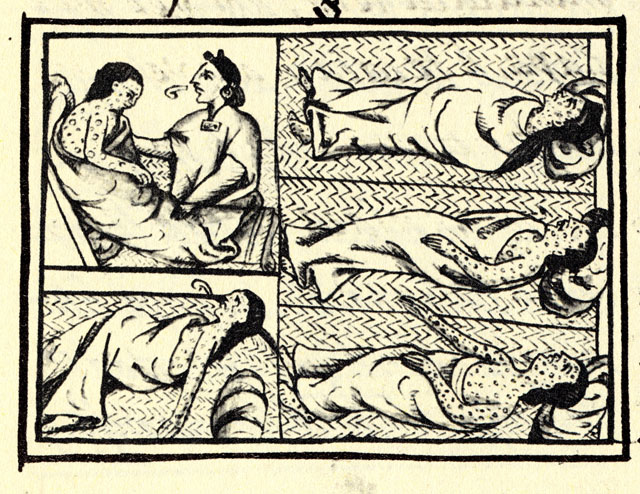

1551-1697 The Spaniards then campaign to conquer other areas and take control of Mesoamerica with their great ally: Smallpox or the Cocolitzi. The Cocoliztli Epidemic or the Great Pestilence was an outbreak of a mysterious illness characterized by high fevers and bleeding which caused 5–15 million deaths in New Spain during the 16th century. The Aztec people called it cocoliztli, Nahuatl for pestilence. It ravaged the Mexican highlands in epidemic proportions, resulting in the demographic collapse of some Indigenous populations. This allowed the Spanish to conquer the Maya civilization in the Yucatán Peninsula of present-day Mexico and northern Central America.

The illustration accompanies text written in Nahuatl, which in English translation says in part: “. . . [The disease] brought great desolation: a great many died of it. They could no longer walk about, but lay in their dwellings and sleeping places, no longer able to move or stir. They were unable to change position, to stretch out on their sides or face down, or raise their heads. And when they made a motion, they called out loudly. The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them, and many just starved to death; starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer.On some people, the pustules appeared only far apart, and they did not suffer greatly, nor did many of them die of it. But many people’s faces were spoiled by it, their faces were made rough. Some lost an eye or were blinded.” English translation is as given in: Lockhart, James (1993). We People Here: Nahuatl Accounts of the Conquest of Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp.181–185.

This is so heartbreaking!

Life in New Spain

For those who survived the spread of diseases, they were forced to work under the encomienda system, a deeply exploitative labor system instituted by the Spanish Crown. Under this system, Spanish conquistadors and settlers were granted vast tracts of land, along with the indigenous people living on that land. These indigenous inhabitants were then compelled to work the fields and mines, their labor and the wealth generated flowing directly to the Spanish landowners, with little to no benefit for the laborers themselves. This forced labor, coupled with the disruption of their traditional ways of life, led to immense suffering and further population decline.

Adding to this oppressive system, the Spanish also brought enslaved Africans to New Spain. Torn from their homelands and families, these individuals endured the horrific transatlantic journey. Upon arrival, they were subjected to the brutal conditions of slavery, forced to labor in mines, on plantations, and in various other capacities. Enslaved Africans were denied their basic human rights and subjected to violence and exploitation.

The Cocoliztli Epidemic also affected some enslaved Africans and to a much less degree the Spaniards.

The Newberry Library, Ayer Fund, 1988

This is a map of New Spain during its maximun expansion:

The Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church actively sought to impose their culture and beliefs on the indigenous people. Viewing their own religion as superior, they embarked on a campaign of forced conversion to Roman Catholicism. This was often justified as a means of saving souls, offering the promise of heaven in exchange for abandoning ancestral spiritual practices.

Catholic priests oversaw the construction of churches throughout Mexico, frequently erecting them on sites previously considered sacred by the local communities, symbolizing the supplanting of indigenous beliefs. To facilitate conversion, the clergy sometimes incorporated elements of local religious traditions into Catholic rituals, a strategy aimed at making the new faith more palatable to the indigenous population. Today, many Catholic traditions in Mexico continue to incorporate native Mexican elements, a testament to the resilience and lasting influence of indigenous cultures.

Even after the indigenous people converted to Christianity, Spaniards largely continued to consider them inferior. This belief contributed to the development of a strict social ranking system based on birthplace, parentage, and perceived ‘racial’ mixing, often reflected in skin color. At the apex of this hierarchy were the Peninsulares, individuals born in Spain. Below them were the Criollos, people of Spanish descent born in Mexico. In the middle were the Mestizos, individuals of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry. It’s important to note that mestizaje continued over time, and today, people with mestizo heritage do constitute the largest demographic group in Mexico. Below the Mestizos were individuals of more complex mixed ancestry, including those with Spanish, African, and indigenous heritage. At the bottom of this social order were the indigenous populations and enslaved Africans, who faced the most severe oppression and discrimination.

1810 The Grito de Dolores: Viva Mexico! Father Miguel Hidalgo, a Criollo priest, issued the “Cry of Dolores” on September 16th, calling for rebellion against Spanish rule. This event is widely considered the start of the Mexican War of Independence. Criollos were frustrated with the lack op political power and seeing all riches coming form their land to Spain. Hidalgo’s initial movement was supported by indigenous people and Mestizos, aimed for social and economic reforms as well as independence.

1811 Hidalgo was captured and executed. Another priest, José María Morelos, took up the mantle of leadership, advocating for a more radical social and political transformation, including the abolition of slavery and racial distinctions. He too was eventually captured and executed in 1815.

Years of Guerrilla Warfare: Following the deaths of Hidalgo and Morelos, the independence movement continued as a series of scattered guerrilla efforts throughout the country. Figures like Vicente Guerrero kept the flame of rebellion alive in the face of continued Spanish resistance.

1921 Plan de Iguala. Initially a royalist military officer, Agustín de Iturbide switched sides in 1820. Fearful of liberal reforms being implemented in Spain that threatened the privileges of the elite in New Spain, he proposed the Plan de Iguala in 1821. This plan offered three guarantees: independence, the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, and the unity of all social groups and the preservation of Catholic religious dominance.

September 16, 1821 Treaty of Córdoba and Independence: The Plan de Iguala gained widespread support from both former insurgents and royalists. Iturbide’s forces entered Mexico City triumphantly, and the Treaty of Córdoba was signed with the remaining Spanish authorities, officially recognizing Mexico’s independence.

Following independence, a constitutional monarchy was established, and Agustín de Iturbide became Emperor Agustín I of Mexico in 1822. However, his rule was short-lived, and he was overthrown in 1823, leading to the establishment of a republic.

This is the Flag of the First Mexican Empire from 1821-1823:

Sources:

- Wikipedia

- Mexico, Enchantment of the World Series. Liz Sonneborn. 2017. Children’s Press.

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- Faces, Cobblestone Publications. Mexico. 2000