One of the most important mathematical creations of human kind is number 0. Kind of ironic when one thinks about this as it partly stands for nothing. However this number is a foundational concept to mathematics, science and technology. On the mathematical side, it enables positional notation allowing us to represent large numbers with a few digits, therefore simplifying mathematical operations.

Zero is essential to solve equations, for calculating and model physical systems. And of course our computers today use a binary system that relies on the use of 0 and 1.

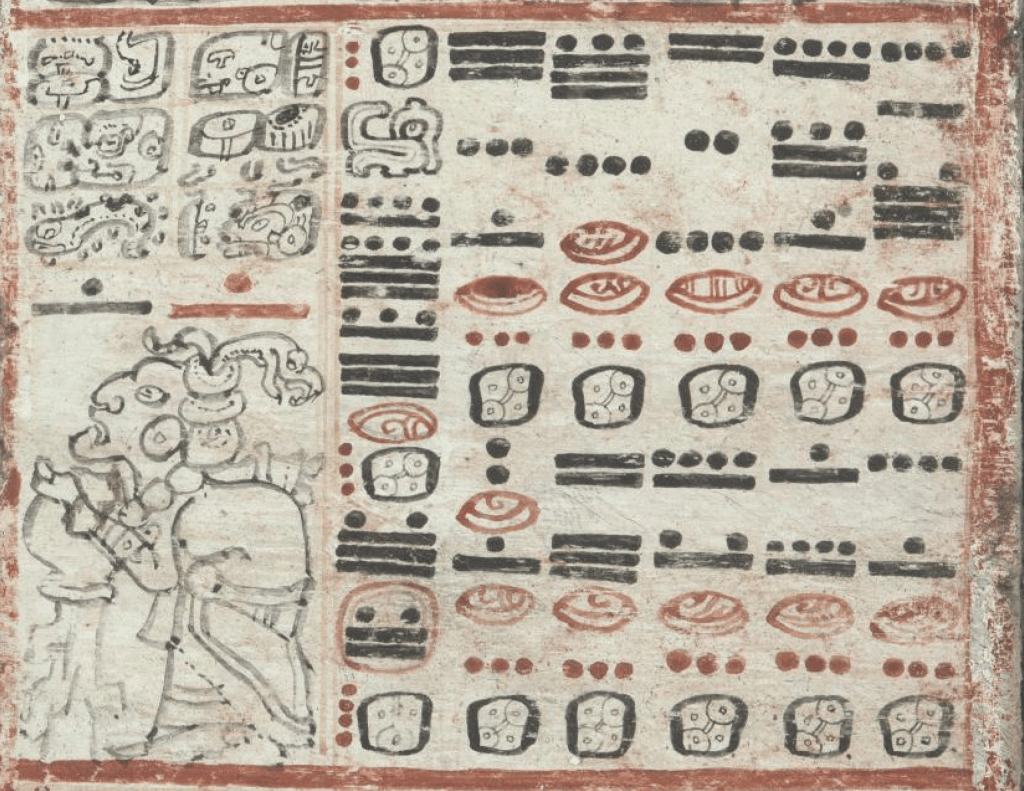

The Maya were one of the oldest civilizations that used the number 0 in both its meaning of nothingness and in its positional notation. This demonstrates their great mathematical knowledge that was even more advanced than Europe’s during their brief existence.

Did you notice that I said used and not created? It is because as our theories of what happened in Mesoamerica’s continue to change and evolve, 0 was a concept that the Maya may have inherited from the Olmecs (a civilization that predates the Maya in their peak classic periods by about 1500 years. ( Olmec Peak: 1200 BCE – 400 BCE, Maya Peak 250 CE – 900 CE.) And it is believed that they did not only spread their mathematical knowledge to the Maya, but also to the Zapotecs (500 BCE – 900 CE).

The oldest number inscriptions in Mesoamerica has been found in a series of plates with human figures denominated Los danzantes. These plates found in the Zapotec city of Monte Alban in the Oaxacan Valley are dated from 500 to 400 BCE.

Some believe that Los Danzantes may have been of Olmec origin and brought to Monte Alban as no other plates like them have been found in other Zapotec centers. As to what they represent the theories point to deceased captives and even the results of an epidemic, as 300 anonymous gravestones have been found with sickly looking humans. (2)

Though 15 number inscriptions have been found on these plates, more research and study is necessary to properly date them.

If you want to read and see more about Monte Alban visit this great Blog:

La Estela 2 de Chiapa del Corzo

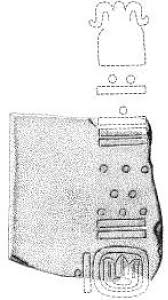

The oldest Mesoamerican artifact that has been scientifically studied and deciphered, is La Estela 2 de Chiapa del Corzo that has the date of : 3 tun 2 winal 13 kin 6 ben, and when the top and bottom is reconstructed based on stylistic comparisons with other pieces., it reads 7.16.3.2.13. 6 ben 13 xul, which would be December 36 BC.

La Estela C de Tres Zapotes

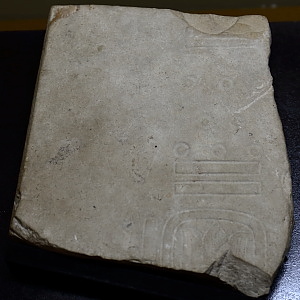

The Tres Zapotes Stela C, a monument carved from basalt, was initially discovered as only its lower half. On one side, it features the abstract figure of a jaguar-being, adorned with a large, elaborate headdress. The other side is inscribed with one of the earliest dates found in Maya numeration: 7.16.6.16.18. This corresponds to September 3, 32 BCE. This inscription is important because it hints at a potential connection between the Olmec and Maya calendrical systems. Some researchers suggest it might commemorate a lunar eclipse that happened two weeks before a solar eclipse. (3)

The lower portion of the stela was unearthed in 1939 by American archaeologist Matthew W. Stirling. He was exploring Mexico’s Gulf Coast to map out the geographical reach of the Maya culture and its ties to neighboring peoples. Thirty years later, in 1969, a farmer found the upper part nearby. This upper fragment, known as the “Covarrubias Stela,” is now housed in the Tres Zapotes site museum in Veracruz. (3)

Cr. Michael Tellebach, reconstruction drawing.

Maya Representation of number 0

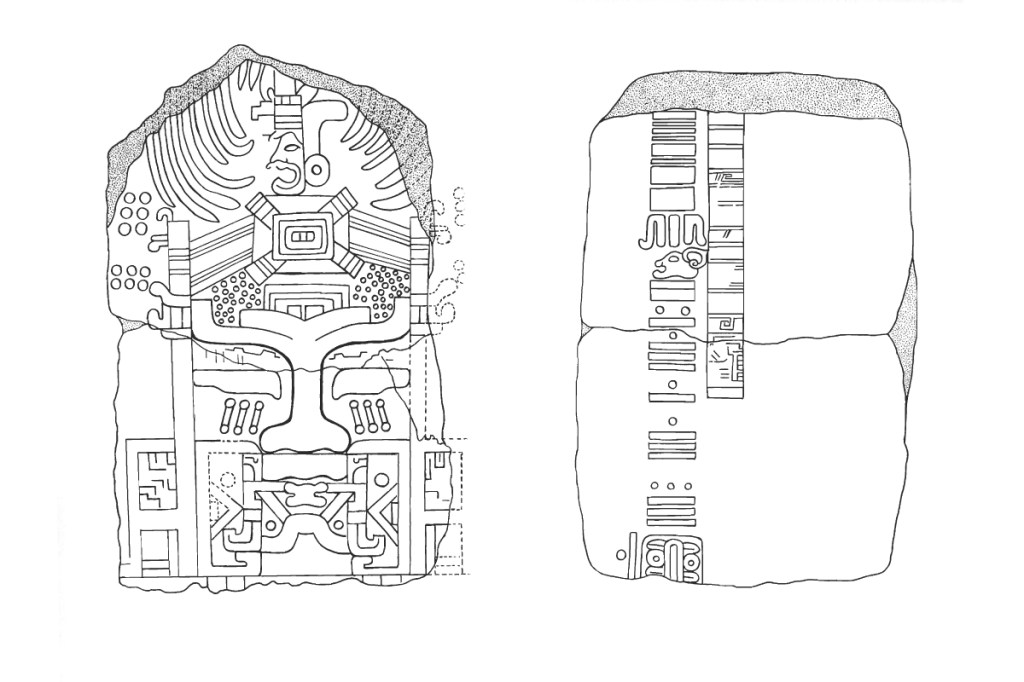

The Mayan civilization represented the number zero with varios symbols: a shell-like symbol, a flower, half a flower and a head with a hand with a horn gesture.

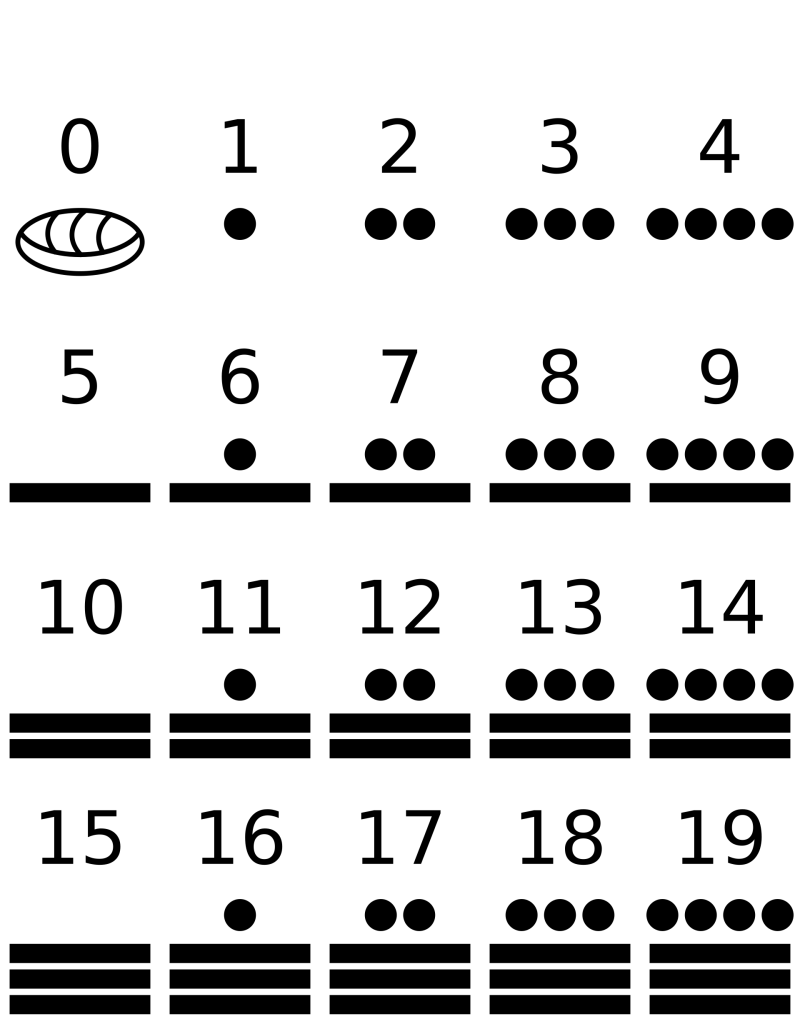

In 1886, Förstemann, who was the director of the Royal Public Library in Dresden and had access to the Dresden Codex, published his findings on the Maya’s numerical and calendar system. He was able to decipher the dot (for one), the bar (for five), and the shell-like glyph as the symbol for zero. This was a crucial discovery because it revealed the Maya’s vigesimal (base-20) number system where zero served as a placeholder, similar to how we use zero in our decimal (base 10) number system.

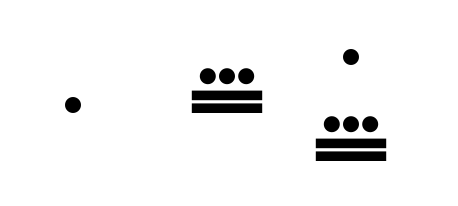

Numbers after 19 were written vertically in powers of twenty:

For example, thirty-three would be written as one dot, above three dots atop two bars. The first dot represents “one twenty” or “1×20”, which is added to three dots and two bars, or thirteen.

Therefore,

(1×20) + 13 = 33

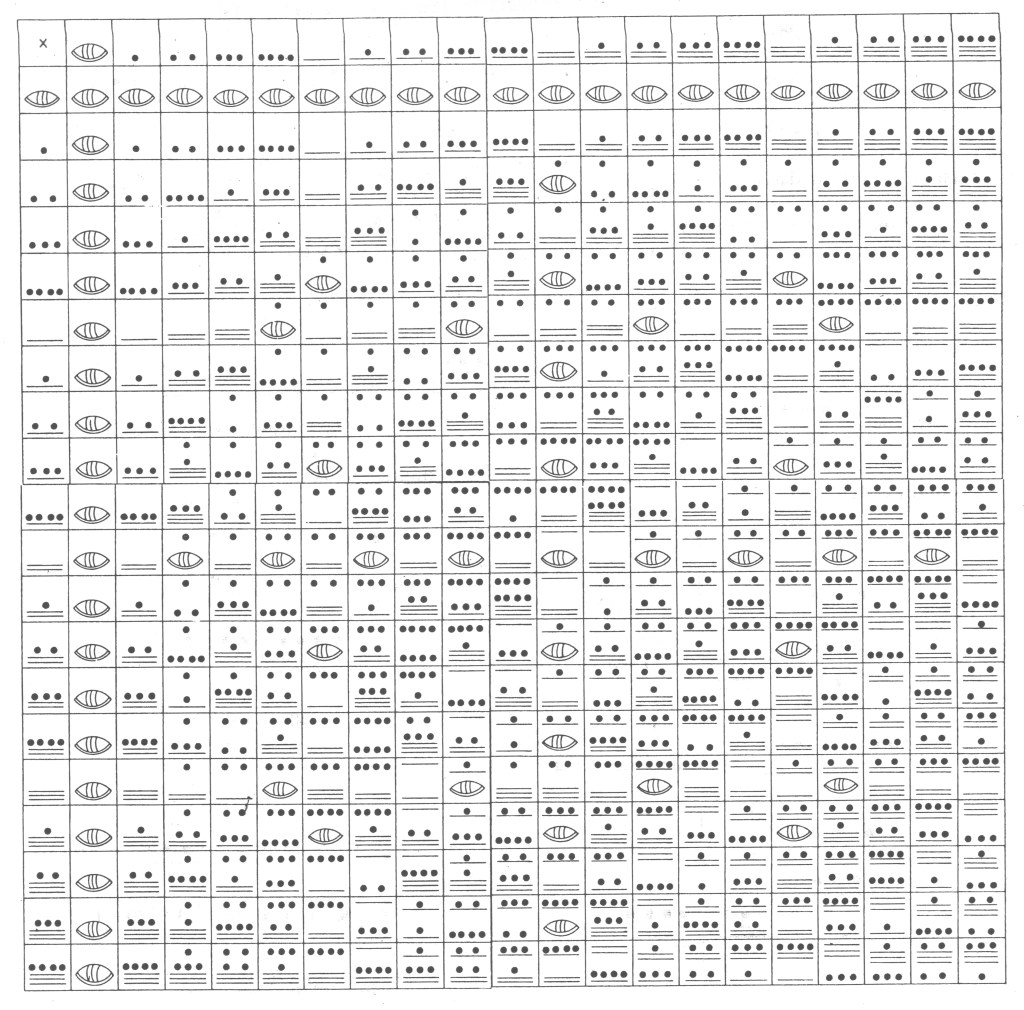

This is a multiplication table with Mayan numbers. (1)

Incredible huh?!

Short Count & Long Count. How the Maya (&Mesoamericans) kept track of time.

The Maya had a fascinating and complex system for tracking time, which involved several interlocking calendars. The two main ways they tracked dates for different purposes are often referred to as the Long Count and the Short Count, though it’s important to understand how they relate to other cyclical calendars like the Tzolk’in and Haab’.

The Maya had a fascinating and complex system for tracking time, which involved several interlocking calendars. The two main ways they tracked dates for different purposes are often referred to as the Long Count and the Short Count, though it’s important to understand how they relate to other cyclical calendars like the Tzolk’in and Haab’.

Here’s a breakdown:

The Maya Long Count

The Long Count is a linear, non-repeating calendar system that meticulously records the total number of days that have elapsed since a mythical creation date. This starting point is generally correlated to August 11, 3114 BCE in the Gregorian calendar.

It’s called “Long Count” because it allows for the precise dating of events over thousands of years, similar to our Western calendar which counts years linearly from a fixed starting point (e.g., Anno Domini/Common Era).

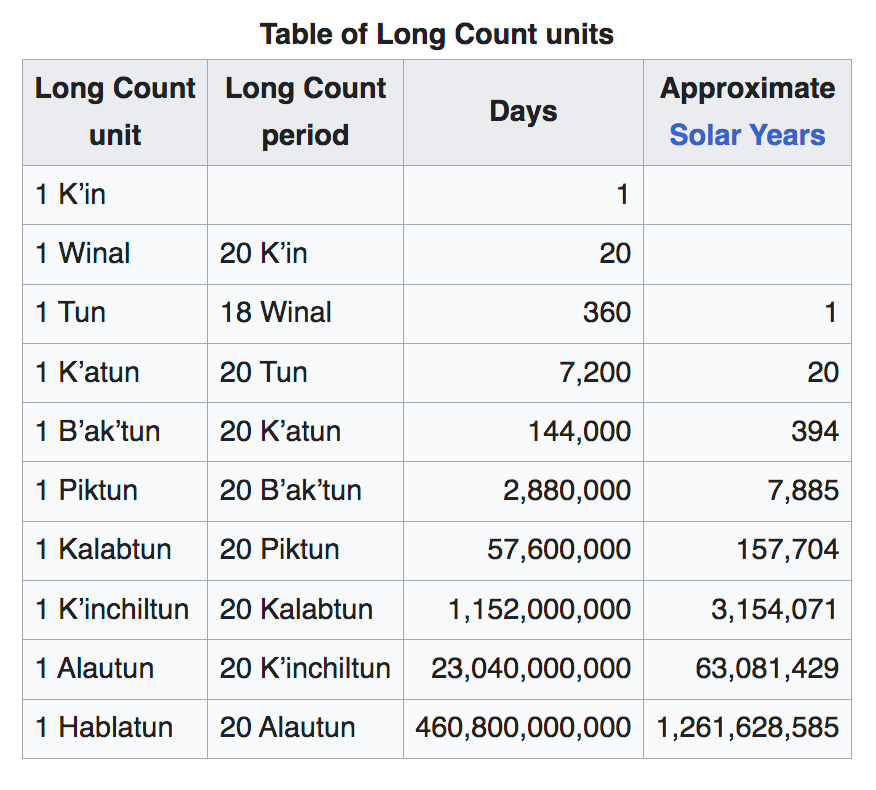

The Long Count uses a modified vigesimal (base-20) system, but with an important exception for the third position. The units are:

- K’in (Kin): 1 day

- Winal (Uinal): 20 K’in = 20 days

- Tun: 18 Winal = 360 days (This is the exception, as 20 Winal would be 400 days. This adjustment makes the Tun closer to a solar year.)

- K’atun (Katun): 20 Tun = 7,200 days

- Baktun: 20 K’atun = 144,000 days

Long Count dates are written as a series of five numbers separated by dots (e.g., 12.19.19.17.19), representing the number of Baktuns, K’atuns, Tuns, Winals, and K’ins, respectively, since the epoch date. This system was crucial for recording historical and mythical events on monuments and stelae, as it provides a unique date that doesn’t repeat within human lifespan. The famous “end date” of December 21, 2012, marked the completion of a 13-Baktun cycle (13.0.0.0.0).

The Maya Short Count (or Calendar Round)

The “Short Count” isn’t a separate calendar system in the same way the Long Count is. Instead, it refers to the Calendar Round, which is the cyclical combination of two shorter, interlocking calendars:

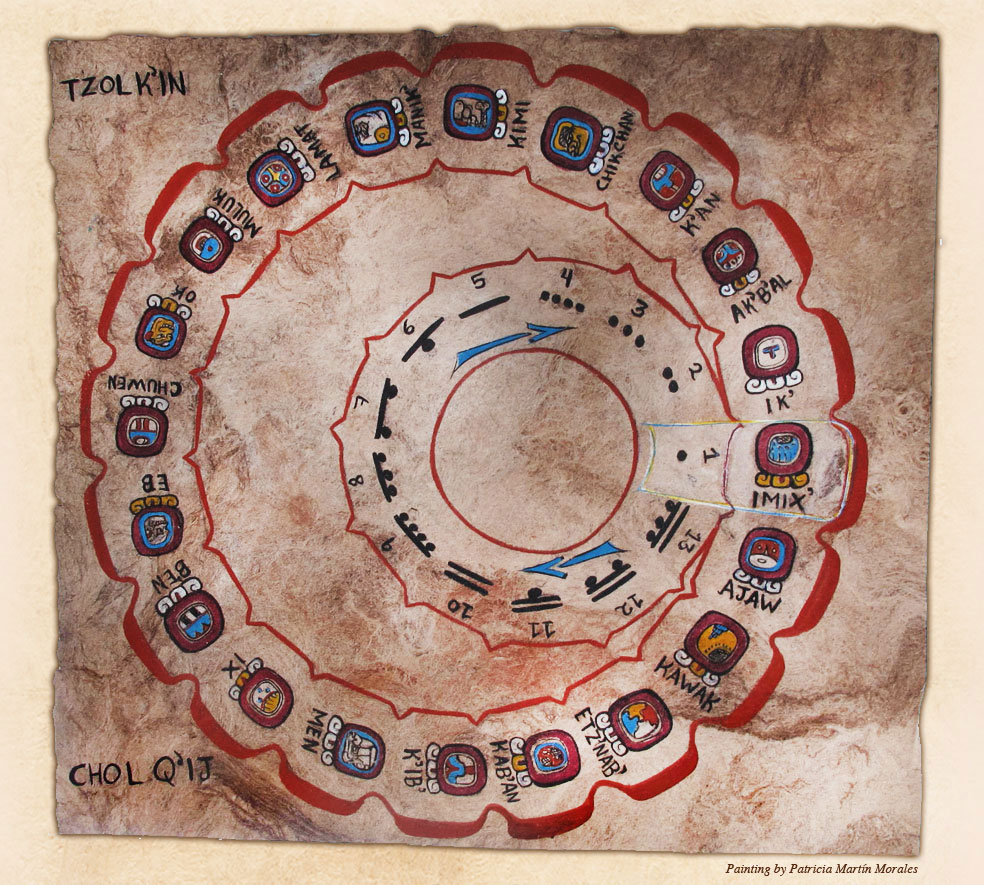

- The Tzolk’in (Sacred Round):

- This is a 260-day cycle.

- It combines 13 numbers (1-13) with 20 day names (e.g., Imix, Ik’, Ak’bal, etc.).

- Each day has a unique combination within the 260-day cycle (e.g., 1 Imix, 2 Ik’, …, 13 Ben, 1 Ix, etc.).

- It was primarily used for ceremonial purposes, divination, and determining the timing of religious and agricultural events.

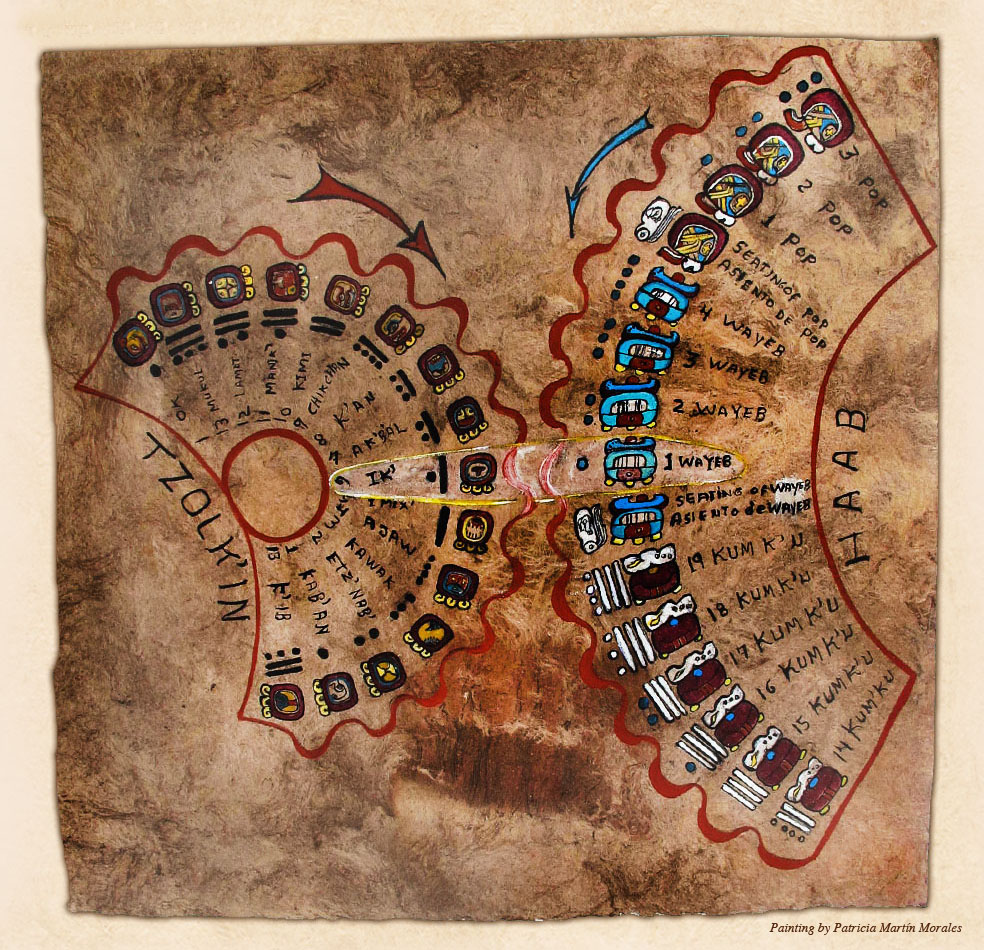

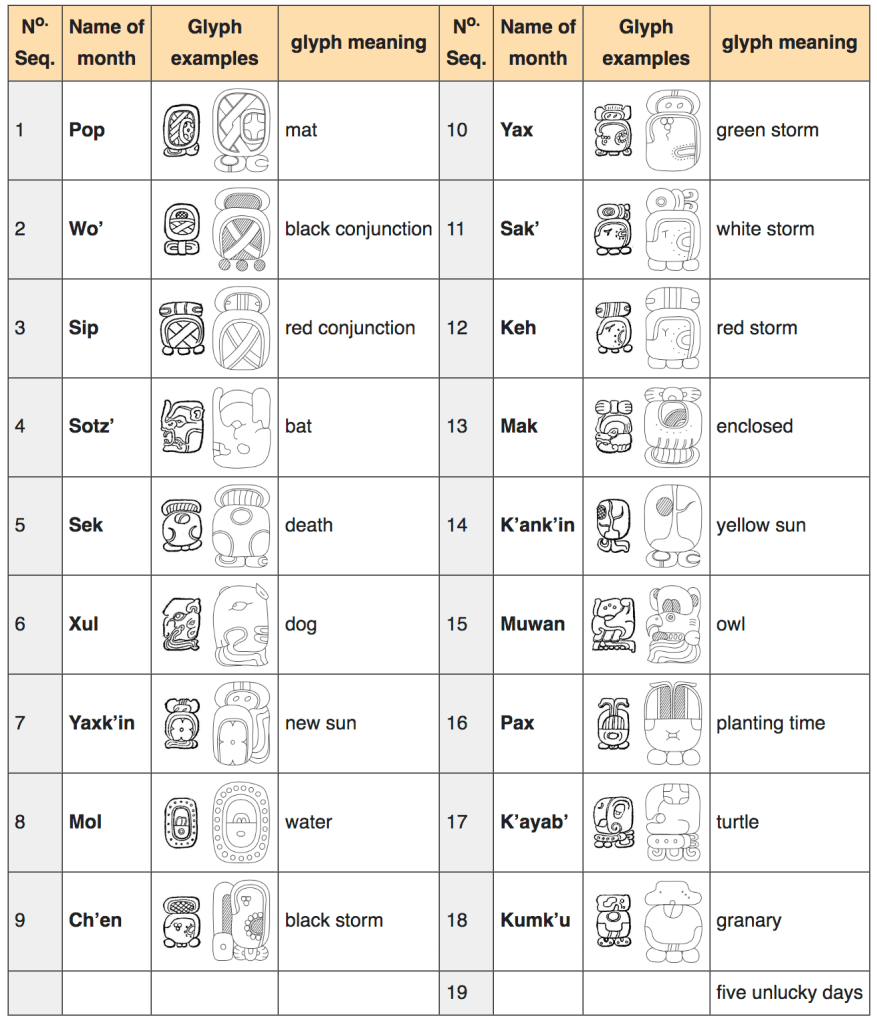

- The Haab’ (Vague Year):

- This is a 365-day solar cycle, similar to our civil calendar.

- It consists of 18 months of 20 days each, plus a final short month of 5 “unlucky” days called the Wayeb’.

- Days are identified by a number (0-19) and a month name (e.g., 0 Pop, 1 Pop, …, 19 Pop, 0 Wo, etc.).

When the Tzolk’in and Haab’ cycles run concurrently, they create a larger cycle of 18,980 days, which is approximately 52 solar years. This longer cycle is known as the Calendar Round. A specific date in the Calendar Round (e.g., “4 Ajaw 8 Kumk’u”) will only repeat every 52 years.

The Tzolk’in (Sacred Round of 260 Days)

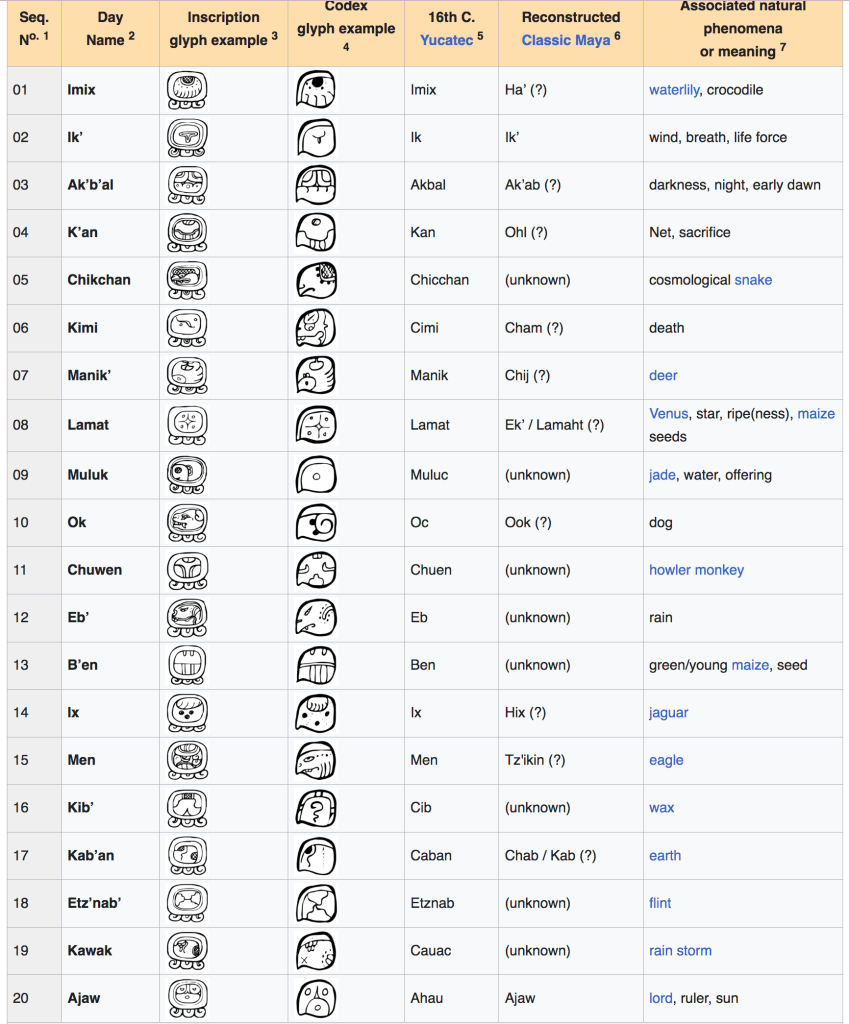

The Twenty Day Names

NOTES:

- The sequence number of the named day in the Tzolkʼin calendar

- Day name, in the standardized and revised orthography of the Guatemalan Academia de Lenguas Mayas

- An example glyph (logogram) for the named day, typical of monumental inscriptions (“cartouche” version). Note that for most of these, several alternate forms also exist.

- Example glyph, Maya codex style. When drawn or painted, most often a more economical style of the glyph was used; the meaning is the same. Again, variations to codex-style glyphs also exist.

- Day name, as recorded from 16th-century Yucatec language accounts, according to Diego de Landa; this orthography has (until recently) been widely used

- In most cases, the day name as spoken in the time of the Classic Period (c. 200–900), when most inscriptions were made, is not known. The versions given here (in Classical Maya, the main language of the inscriptions) are reconstructed based on phonological comparisons; a ‘?’ symbol indicates the reconstruction is tentative.

- Each named day had a common association or identification with particular natural phenomena

The Ancient Maya used the Tzolkʼin in inscriptions and codices. Symbolism related to the Tzolkʼin is also observed in the Popol Vuh (which, though written in the early post-conquest period, is probably based on older texts). The Popol Vuh is the foundational sacred text recounting the mythology and history of the K’iche’ Maya people of Guatemala. It is considered one of the most important surviving documents of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican literature.

The Modern Maya used their Tzolk’in (260-day sacred calendar) for various crucial aspects of life:

Agriculture: They timed maize planting and harvesting with specific zenith transit days, such as April 30 before the rainy season and August 13 for dry corn harvest.

Training & Initiation: The 260-day cycle mirrored human gestation, guiding the training and “rebirth” initiation of “calendar diviners” (Aj Kʼij), suggesting a possible origin as a midwife’s calendar.

Rituals: The Tzolk’in dictated the timing of ceremonies, including the “Initiation” celebration of 8 Chuwen.

Auspicious Timing: Specific days were deemed favorable for certain actions, like weddings (Akʼabʼal, Bʼen) or construction (Kʼan).

Divination: They practiced divination by casting lots and interpreting future days based on the calendar, sometimes influenced by physical sensations.

Personal Identity: Traditional Maya names were often based on birth days, with personal characteristics and the success of endeavors believed to be influenced by the day’s name, similar to astrology.

The Haab’ (Vague Year)

The Haabʼ comprises eighteen months of twenty days each, plus an additional period of five days (“nameless days” or “unlucky days”) at the end of the year known as Wayeb’ (or Uayeb in 16th-century orthography).

When the Tzolk’in and Haab’ cycles run concurrently, they create a larger cycle of 18,980 days, which is approximately 52 solar years. This longer cycle is known as the Calendar Round. A specific date in the Calendar Round (e.g., “4 Ajaw 8 Kumk’u”) will only repeat every 52 years.

Bricker (1982) estimates that the Haabʼ was first used around 500 BCE with a starting point of the winter solstice.

This video shows how it works:

The Maya Long Count

The Maya Long Count

The Long Count is a linear, non-repeating calendar system that meticulously records the total number of days that have elapsed since a mythical creation date. This starting point is generally correlated to August 11, 3114 BCE in the Gregorian calendar.

It’s called “Long Count” because it allows for the precise dating of events over thousands of years, similar to our Western calendar which counts years linearly from a fixed starting point (e.g., Anno Domini/Common Era).

The Long Count uses a modified vigesimal (base-20) system, but with an important exception for the third position. The units are:

- K’in (Kin): 1 day

- Winal (Uinal): 20 K’in = 20 days

- Tun: 18 Winal = 360 days (This is the exception, as 20 Winal would be 400 days. This adjustment makes the Tun closer to a solar year.)

- K’atun (Katun): 20 Tun = 7,200 days

- Baktun: 20 K’atun = 144,000 days

The name bʼakʼtun was invented by modern scholars. The numbered Long Count was no longer in use by the time the Spanish arrived in the Yucatán Peninsula, although unnumbered kʼatuns and tuns were still in use. Instead the Maya were using an abbreviated Short Count.

Long Count dates are written as a series of five numbers separated by dots (e.g., 12.19.19.17.19), representing the number of Baktuns, K’atuns, Tuns, Winals, and K’ins, respectively, since the epoch date. This system was crucial for recording historical and mythical events on monuments and stelae, as it provides a unique date that doesn’t repeat within human lifespan. The famous “end date” of December 21, 2012, marked the completion of a 13-Baktun cycle (13.0.0.0.0).

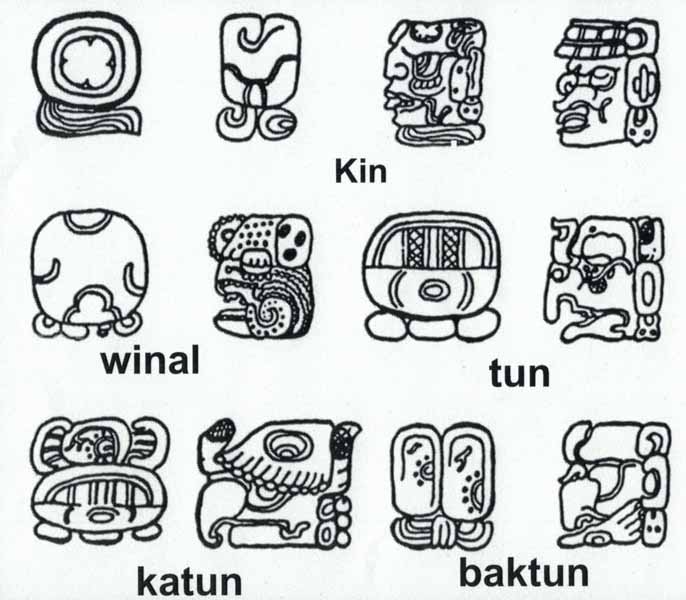

This is the graphic representation of each unit in their writing in monuments and codexes:

Understanding how to know the date on astelae or codex is a lot of work .There are ways to do it with the Gregorian and even the Julian Calendar. You can go HERE is you are interested in reading how it is done.

There is a famous place known for its Mayan Stela in Quirigua, Guatemala where one can see the use of Mayan long count in all its splendor. By the way HERE is a great blog with all the Stelae of Quirigua, they are so beautiful!

Below is the east side of Stela C with the creation date of 13.0.0.0.0 It is absolutely fascinating!

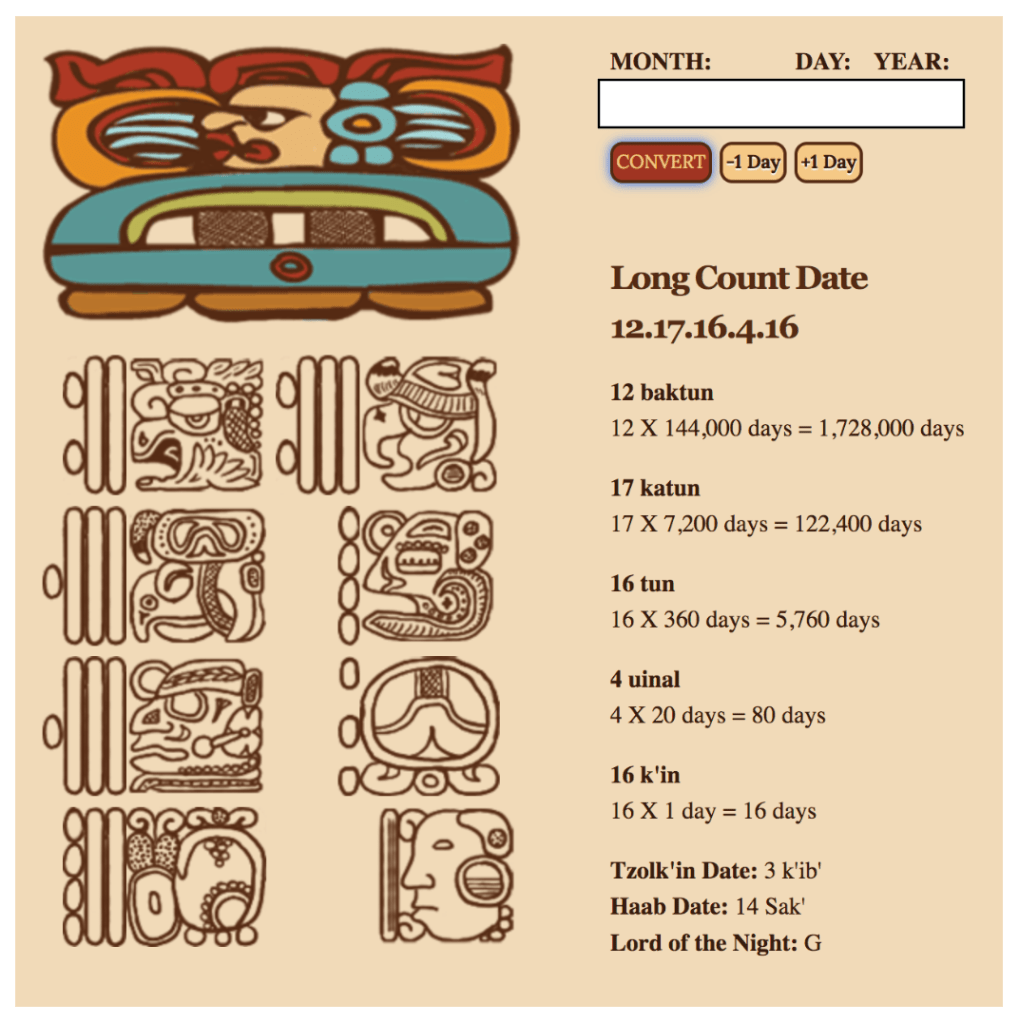

I get goosebumps becasue I absolutely love number 13. And it goes beyond the fact that I was born on a 13th… now I want to know what my birthday would be in their calendar! And guess I found a place where you can do it! It is a Maya Calendar Converter. It even gives one the Graphic! Try it!

So I was born on:

Tzolkin Date: 3 Kib

Haab Date: 14 Sak

Lord of the Night: G

Or more precisely:

SO cool!!!!

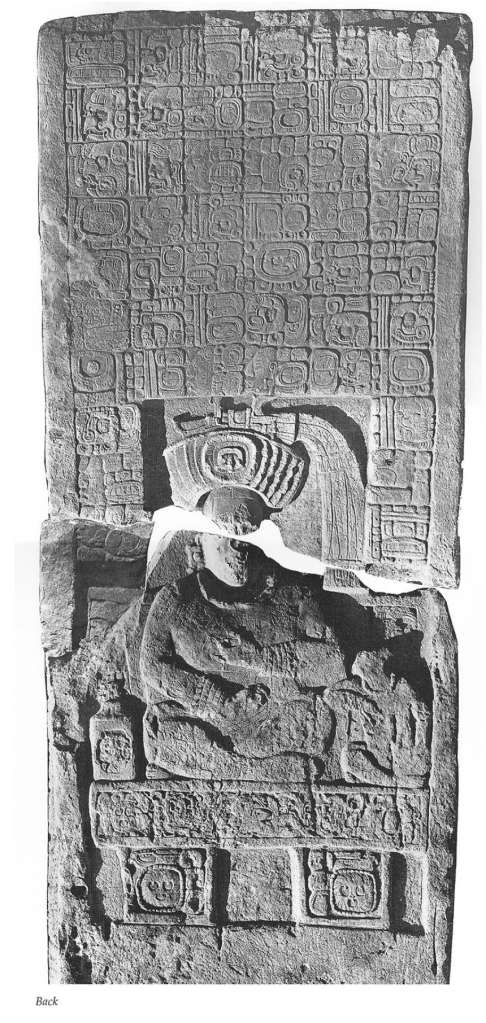

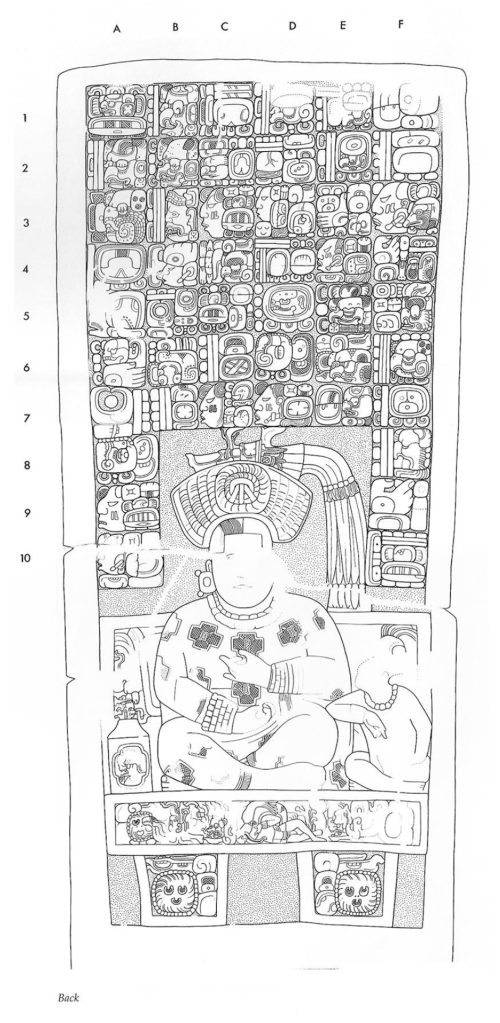

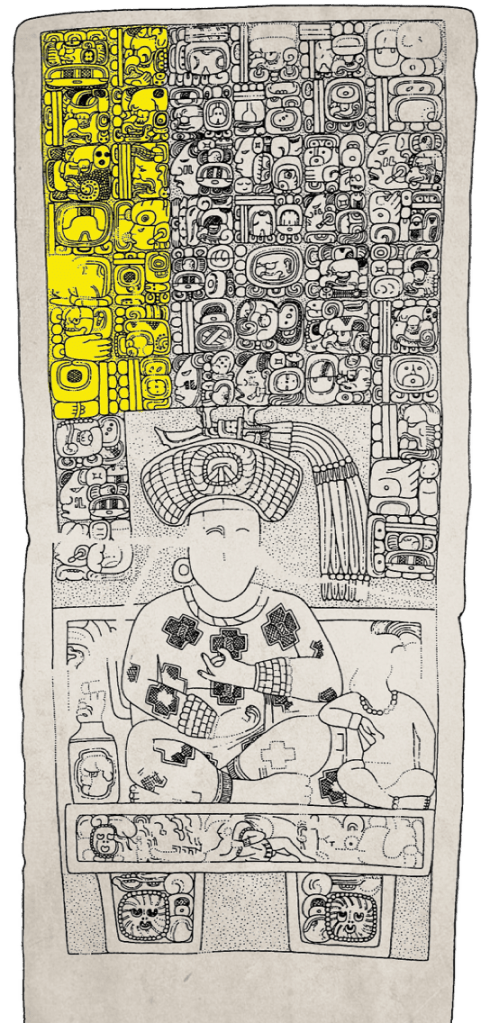

This is another dated Stela I found. It is Stela C of a site in Piedras Negras, Guatemala. Here is the Stela in both drawing and photo. Cr. Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology.

Here is the description I found via: https://www.jaguarstones.com/maya/mayacalendar.html

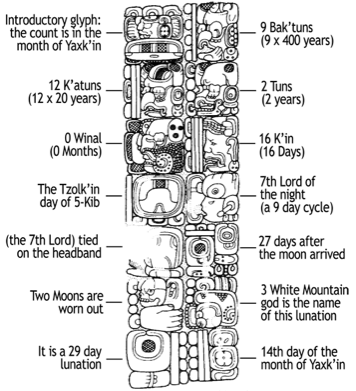

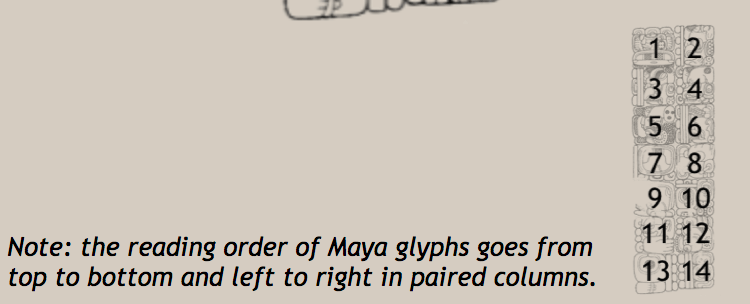

The monument on the right is Stela 3 from the Maya city now known as Piedras Negras. It tells the story of a Maya queen named Lady K’atun Ahaw of Namaan. (Namaan was the Mayan name for the present-day city of La Florida in Guatemala.) The inscriptions begin with an introductory glyph like a drumroll signaling to the reader that a date is coming. The glyphs that follow are the Long Count dates showing how many bak’tuns, k’atuns, tuns, winals, and k’ins have passed since the world began.

These are followed by the specific day from the ritual Tzolk’in calendar (5-Kib). Next comes the supplementary series, which in this case includes one of the nine Lords of the Night who ruled each day, as well as a cluster of glyphs to show the precise day within the Lunar Cycle. Last, the mason carved the day and month of the Haab calendar (14-Yaxk’in). In the sidebar you’ll find a translation of the calendar glyphs that start this inscription.

And last, this is the Chinkultic Disc. It stands out as a remarkably beautiful Maya marker for a “pelota” game and a striking example of the Maya calendar. It bears the Maya date 0.0.9.7.17.12.14. / Gregorian year 568/569 AD. This is because two solar eclipses occurred over the Yucatán just seven months apart, on December 4, 568, and May 31, 569. This unique and rare astronomical event is quite extraordinary in human history and was recorded so gracefully by the Maya:

Last week I visited the MFA’s Maya collection and I plan to visit the Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology soon. I will then create another post about my discoveries in both museums! So you can look forward to that. Thank you for coming along!

And by the way, in case you are wondering. This is a Mexica / Aztec Calendar, it is NOT from the Maya. So many mistakes online about it!

Sources:

0) Wikipedia

1) Los Señores del Cero. El conocimiento matemático en Mesoamerica. Juan Tonda 7 Francisco Noreña. Pangea Publications. Sadly it is a copy of the book and has no date. Should have learned form the Maya!

2) Archaeotravel.eu: “Monte Alban – Are the Danzantes Evidence for an Epidemic?” In Uncovered History. Robin Hayworth, 2014.

3) Museo Nacional de Antropologia, México. La Estela C de Tres Zapotes.

4) https://www.mayaarchaeologist.co.uk/ Written by Dr. Diane Davies, a Maya archeologist, her website is great to learn About the Maya Calendar and mathematics. Thank you Dr. Davies! I laerned so much from you!

5) Maya Calendar Converter: https://maya.nmai.si.edu/calendar/maya-calendar-converter

6) Jaguar Stones.com, for a stela date interpretation https://www.jaguarstones.com/maya/mayacalendar.html

7) This is an incredible museum and its website has ongoing research on Mayan artifacts: https://peabody.harvard.edu/corpus-maya-hieroglyphic-inscriptions

1 Comment