The second exhibit about the Maya I visited was in The Peabody Museum of Archeology and Enthnology at Harvard University. This museum is renowned for its extensive Mesoamerican collections, and its Maya stelae are a major highlight. While they have original artifacts, the Peabody is particularly famous for its collection of plaster casts of Maya monuments, including many stelae.

When you walk into the museum you see many stairs, the Latin America exhibits are on the 3rd floor. This is the entrance:

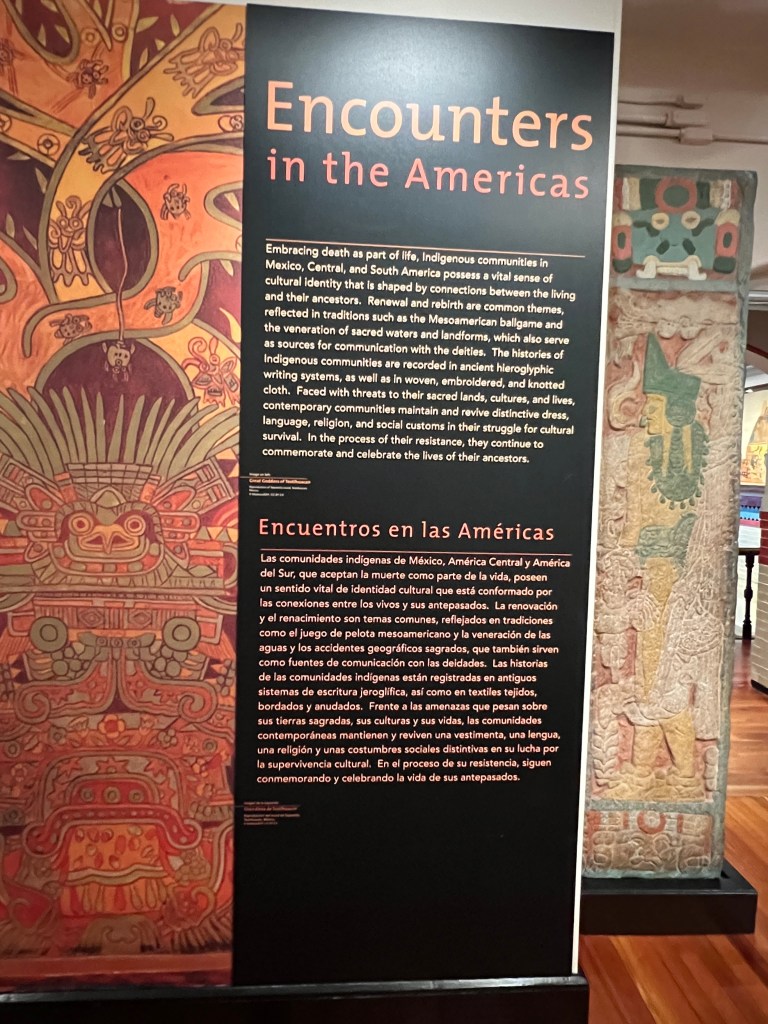

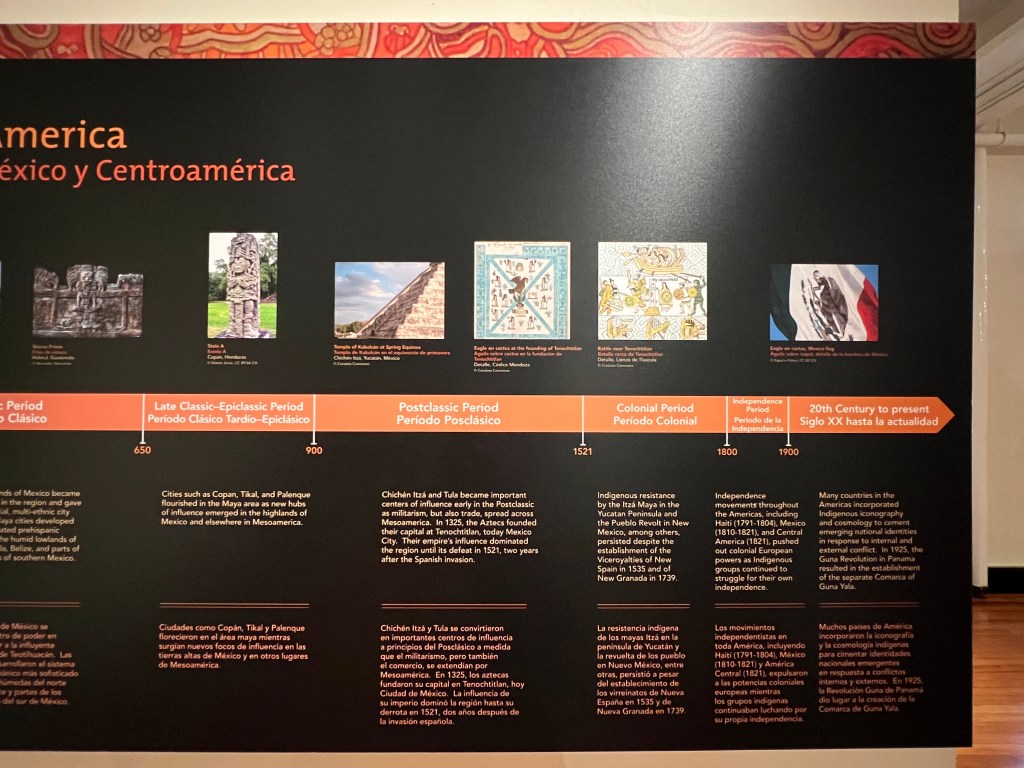

The gallery is called Encounters in the Americas:

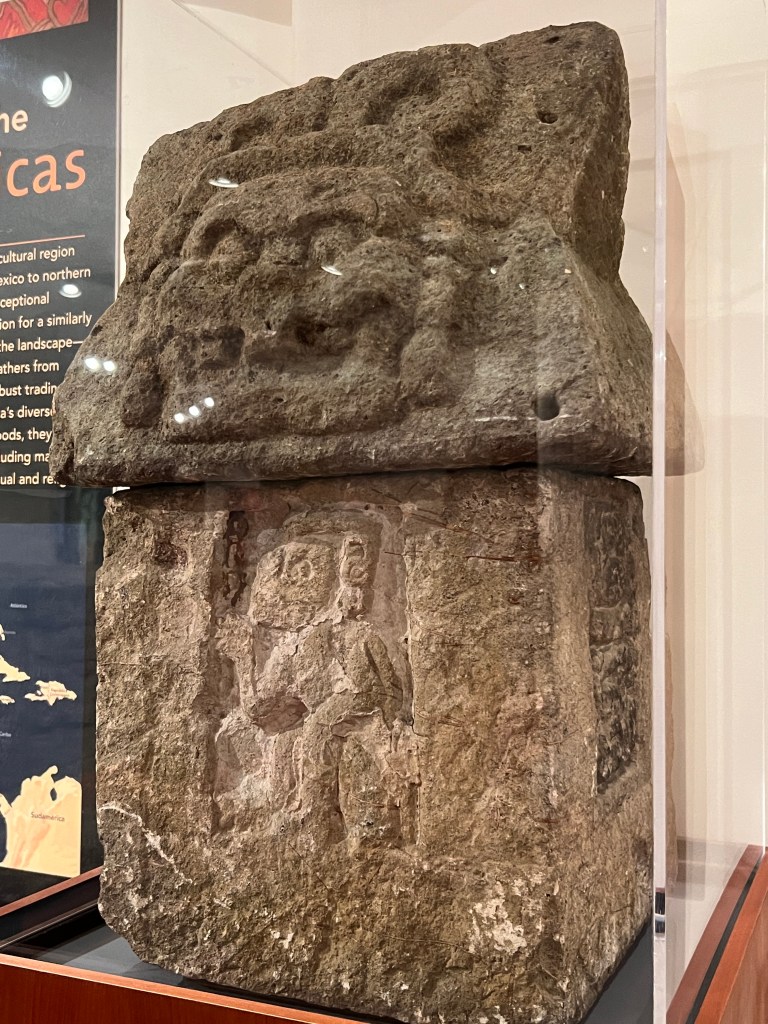

Altar Q

And this is the first artifact one sees: Altar Q

A more complete view:

This altar is incredible and was found in Copán, Honduras. This is a plaster made from the original. Altar Q is a large, rectangular stone altar carved with full-body portraits of all sixteen kings of Copán’s dynastic lineage. They are depicted in chronological order around its four sides. This makes it one of the most complete and clear “king lists” in the entire Maya region.

This is what the original looks like from a photo in the museum’s website. My guess from the time it was found.

When you read “this is a plaster made from the original” you probably thought “Oh… it’s not original”… just like I thought when I read it there. But these are no mere replica, they represent a crucial part of the history of Maya archaeology.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, expeditions from institutions like the Peabody Museum, often led by figures like Teobert Maler, ventured into the Maya lowlands to document and create molds of these monumental sculptures. These molds allowed for the creation of plaster casts, which could then be studied and exhibited in museums far from their original jungle settings.

Many of these original monuments have since suffered from erosion, looting, or other damage, making the Peabody’s casts invaluable records of what these incredible works of art looked like.

So this cast is probably better than the original now. So let’s take a closer look at it…

Separated in time by some 340 years, the altar and bases are a replication of K’nich Yax Kuk’ Mo”s funerary bench. The altar Is testimony to a strong visual memory of historic events at the site. Placed In front of the pyramidal sequence that houses the founder’s tomb at its core, Altar Q is a tribute to K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ that also served to legitimize Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, Ruler 16, within the dynastic line.

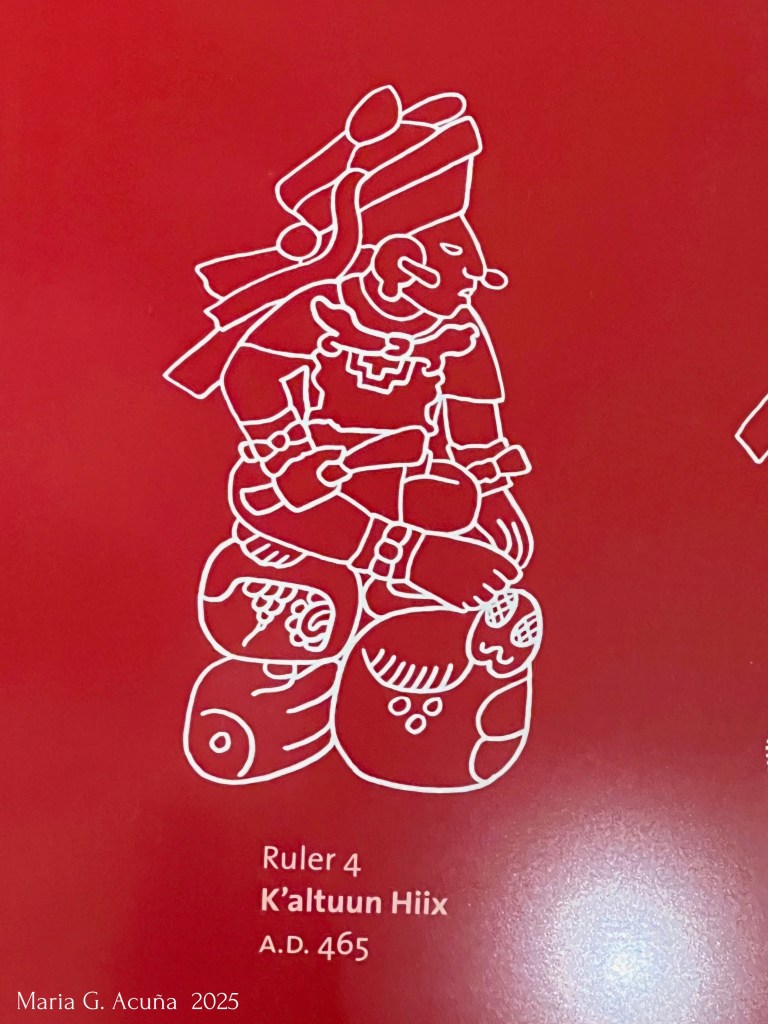

The one on the right is detailed in this drawing:

And this was so incredible…

Altar Q was found at the base of Structure 16, the most important ceremonial and royal pyramid in the city of Copán. Temple 16 is not just a single building, but a culmination of at least five stages of construction, each built on top of and encasing previous ones. This layering is a common practice in Mesoamerican architecture, where new rulers or significant events often led to the construction of a larger, more elaborate temple over an older one, metaphorically strengthening connections to the past and asserting new authority.

Specifically, it was located at the bottom of the staircase leading up to the temple. The altar was placed there by the sixteenth ruler of Copán, Yax Pasah, according to Maya history sites.

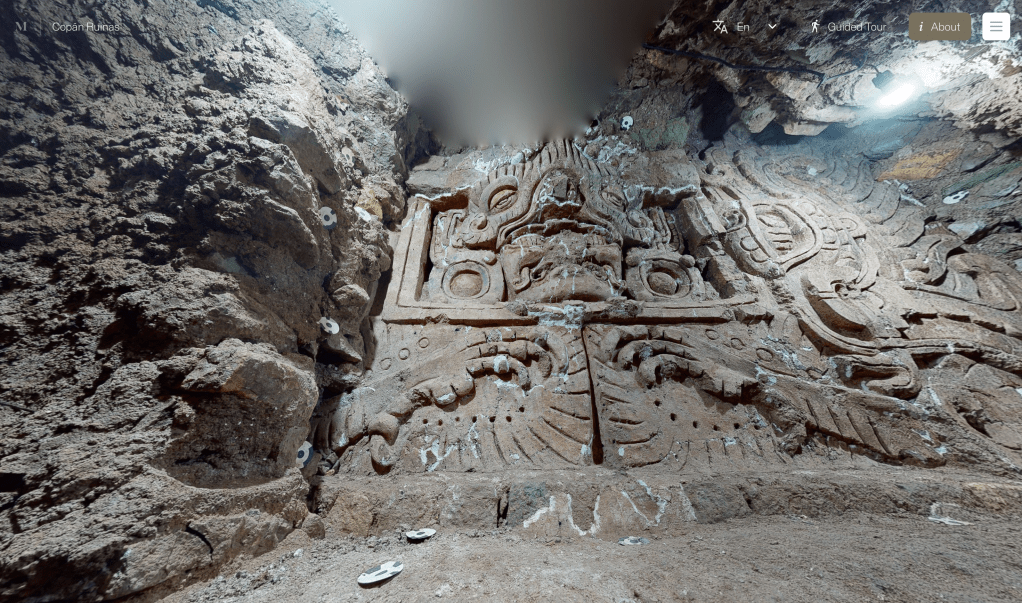

It is incredible to take a piece I saw at a museum and realize where it was in the actual site… and while doing this I was so impressed with another structure found underneath that pyramid: The Rosalila Temple:

The Rosalila Temple (also known as Structure 10L-26) is an exceptionally well-preserved Maya temple found deep within Temple 16 at Copán, Honduras. It was built around A.D. 570 by the 10th ruler, Moon Jaguar. The tomb of Copán’s dynastic founder, K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, was found directly underneath the central room of the Rosalila temple

What makes Rosalila unique is that it wasn’t destroyed; instead, it was ritually encased and buried by later constructions, preserving its incredible detail. It was discovered in 1989 by Honduran archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle.

Rosalila is famous for its vibrant, polychrome stucco decorations, depicting deities and cosmic imagery, offering a rare glimpse into Early Classic Maya art. A life-size replica is meticulously reconstructed in the Museo de Escultura Maya de Copán, allowing visitors to experience its grandeur.

It is otherworldly! Is it not?

How would you like to go there virtually? Well I found an incredible website called Mused.com where you can travel virtually to museums and incredible places all around the world. In this case you actually walk inside the pyramid! And see parts of the Rosalila Temple … now it took me a while to get my bearings… I’m not spatially great! So after like 15 minutes of aimless wondering (which I enjoyed greatly!) I was able to figure out that there is a tour. HERE is the beginning of it and just hit next! And if you want to “free explore “you can move by floors, I found the image depicted below doing that… HERE.

This is the at the bottom of the temple according to this detailed drawing:

I was so excited when I found that! I almost felt like I was there! This is a map of Copán and you can see the location of Structure 16, the main pyramid:

You can read more about this Pyramid and its surrounded structures HERE.

And this is a great video of Copán from the UNESCO:

The Hieroglyphic Stairway

Before we move on to the Stelae I saw, I wanted to highlight another incredible pyramid that was also part of the city of Copán and briefly mentioned in the hallway leading to the gallery of MesoAmerican art at at the Peabody. It is called The Hieroglyphic Stairway and it is Structure or Temple 26.

The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán: A Monumental Text

The Hieroglyphic Stairway at the ancient Maya city of Copán in Honduras is arguably the longest and most famous hieroglyphic inscription in the entire Maya area. It’s a monumental staircase carved with an extraordinary amount of glyphs, making it a priceless historical record. It was the most significant feature of Outstanding Universal Value cited by UNESCO for designating Copan a World Heritage Site in 1980.

What It Is

The stairway forms part of Temple 26 and consists of 63 steps, each meticulously carved with hieroglyphic blocks. In its final form, it contained over 2,200 glyphs, recounting the dynastic history of Copán’s rulers from the 5th to the 8th century CE. Interspersed among the glyph blocks are large, seated sculptural figures representing some of the past kings, further emphasizing the royal narrative. This vast stone “book” was primarily commissioned and completed around 755 CE by Ruler 15 (K’ak Yipyaj Chan K’awiil), though an earlier version was started by Ruler 13 (18 Rabbit).

Discovery and Early Challenges

The Hieroglyphic Stairway was first extensively explored and recognized as a continuous inscription by British archaeologist Alfred Percival Maudslay in 1885. When discovered, much of the stairway had collapsed due to earthquakes and natural deterioration, leaving the thousands of carved blocks in a jumbled mass at the base of the pyramid.

The Peabody Museum at Harvard University led early excavations from 1892 to 1900, attempting to clear and document the monument. However, without a full understanding of Maya writing, much of the reconstruction work, particularly by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in the 1930s and 40s, was unfortunately done with many blocks out of their original order. This meant that while the stairway was physically reassembled, its textual message remained largely incoherent for decades.

You can see a lot of images of this time at the Peabody Website HERE. This was as you came into the gallery:

This is a photograph of what it looked like when it was reconstructed out of order. notice it has no protection from the elements:

The Decipherment Journey

The decipherment of the Hieroglyphic Stairway has been a monumental, ongoing effort spanning over a century:

Early Attempts (late 19th – mid-20th century): Without a working key to Maya hieroglyphs, early scholars could only identify dates and some calendrical cycles. The jumbled nature of most of the stairway’s blocks made any attempt at reading a continuous narrative nearly impossible.

Breakthroughs in Decipherment (1960s onwards): The field of Maya epigraphy (the study of Maya writing) saw significant breakthroughs starting in the 1960s, notably with the work of Tatiana Proskouriakoff, who demonstrated that many inscriptions recorded historical events and dynastic histories, not just astronomical data.

Hieroglyphic Stairway Project (1980s – Present): With a better understanding of Maya script, a concerted effort began in the late 20th century to re-evaluate the Hieroglyphic Stairway. This included archaeological excavations to understand the pyramid’s construction phases and meticulous epigraphic work.

Scholars like David Stuart, William Fash, and others have dedicated years to studying every block, using surviving historical photographs from the early excavations (like those from the Peabody Museum’s archives), careful analysis of the carvings, and contextual clues from other monuments at Copán.

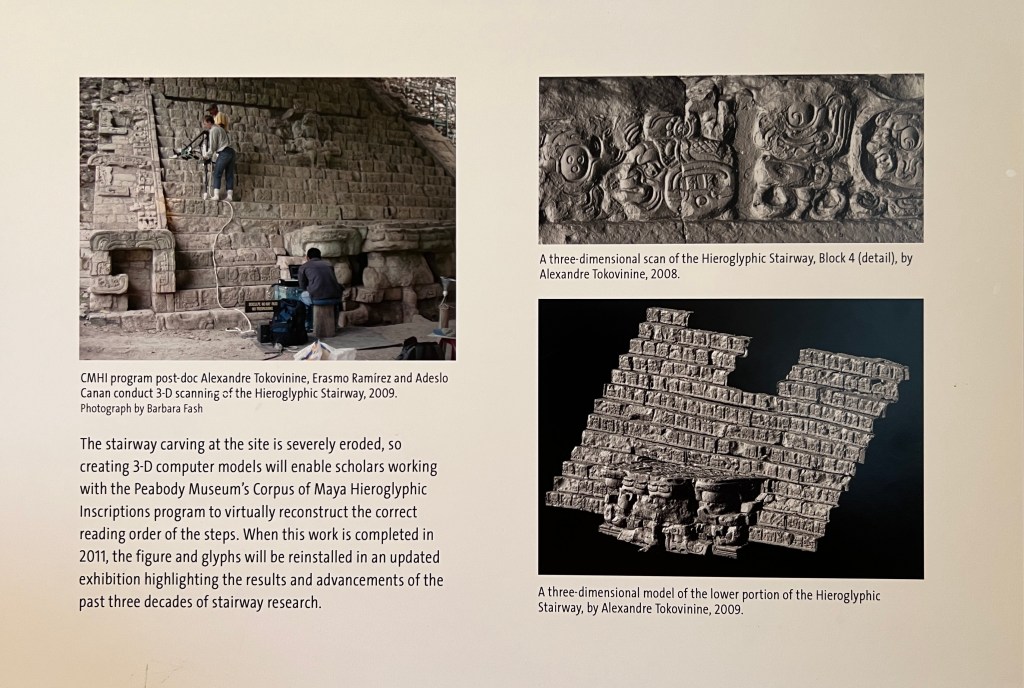

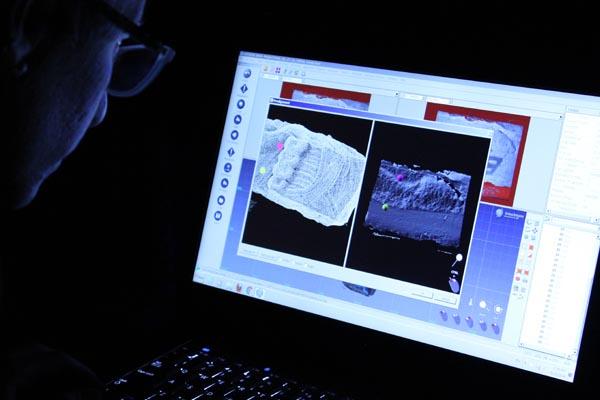

Advanced Technology: More recently, 3D scanning initiatives (from 2008-2012, involving the Peabody Museum) have captured the entire inscription at high resolution. These digital models are crucial for virtually reconstructing the stairway’s original order, allowing epigraphers to read the text as it was intended. A CMHI (Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, one of their research groups) publication specifically about the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán is in progress.

Digital scanning offers a non-invasive method to create detailed, undistorted records of ancient Maya material heritage. This technology safeguards incredibly rich artifacts from environmental deterioration, negligence, and vandalism. Each 3D model is generated from multiple overlapping scans captured from various angles, with the CMHI specifically employing a portable optical system that projects structured white light onto the object’s surface.

Today, epigraphers can read about 80% of the legible text on the Hieroglyphic Stairway. It recounts the story of Copán’s dynastic line, highlighting the accomplishments and major events of its kings, including tributes to earlier rulers and the pivotal burial of Ruler 12. Despite the early misalignments in its reconstruction, ongoing research continues to unlock the full narrative of this incredible ancient document.

This is what the pyramid looks like today with a protective tent. Like finally!

And HERE is your opportunity to see this incredible stairway as if you were there by the incredible site Mused.

Something that made me very sad was to see the degree of decay of the inscriptions. Look at the difference:

And this is a screen shot from the exploration at Mused:

It is so sad that so much of it has been lost. But to end this part in a good note, I was in absolute awe of the research published about the Maya available for us to see from the incredible archive of the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology at Harvard: HERE. And that is only a part of it!

The Stelae

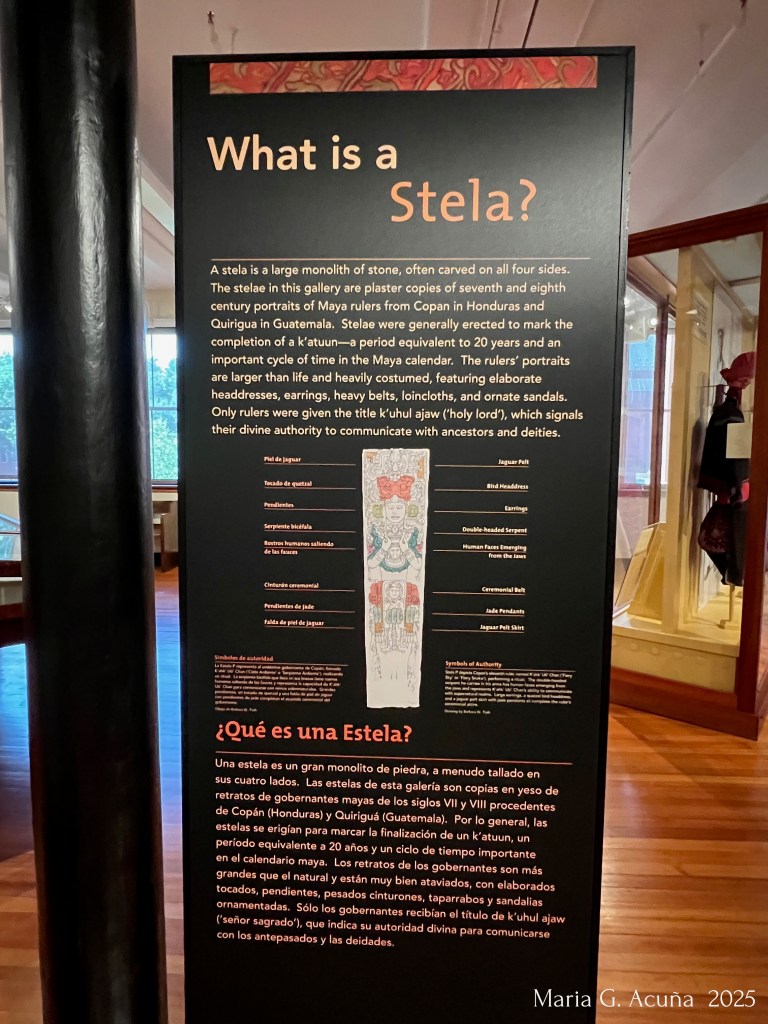

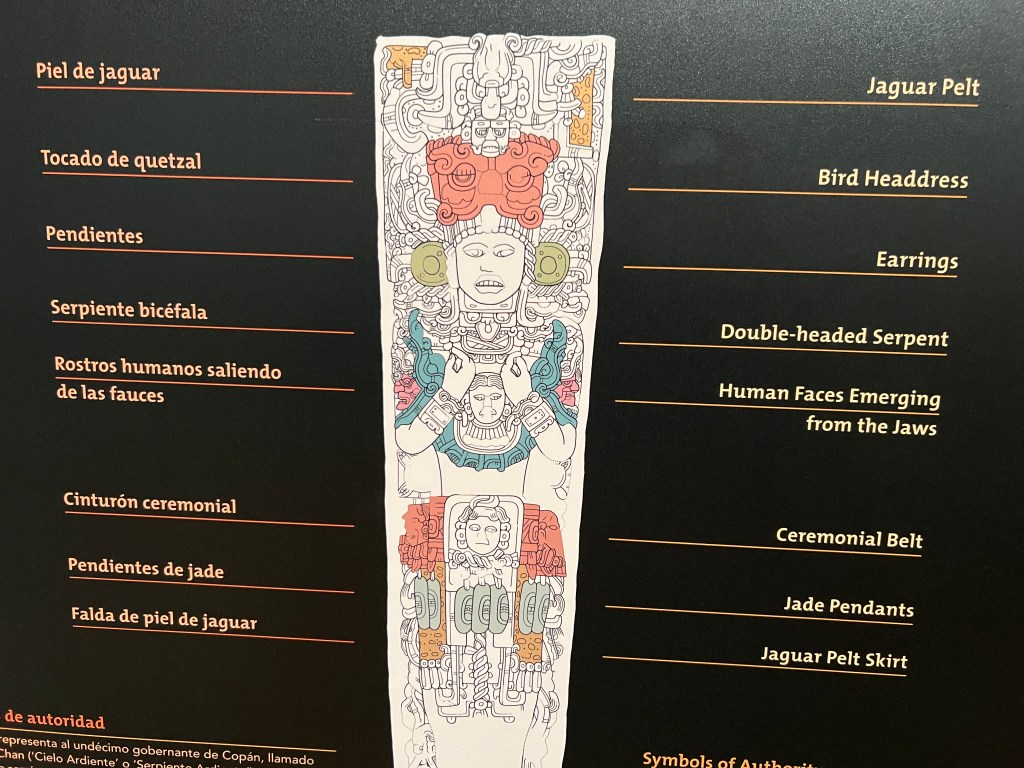

This is the description of museums curators as what the Stelae in the exhibit were:

A stela is a large monolith of stone, often carved on all four sides. The stelae in this gallery are plaster copies of seventh and eighth century portraits of Maya rulers from Copan in Honduras and Quirigua in Guatemala. Stelae were generally erected to mark the completion of a k’atuun—a period equivalent to 20 years and an important cycle of time in the Maya calendar. The rulers’ portraits are larger than lite and heavily costumed, featuring elaborate headdresses, earrings, heavy belts, loincloths, and ornate sandals.

Only rulers were given the title k’uhul ajaw (‘holy lord’), which signals their divine authority to communicate with ancestors and deities.

The leading archeologist that made these plasters possible was a man called Alfred Percival Maudslay (1850–1931). He was a British archaeologist often considered the “father of Maya archaeology.” He revolutionized the study of ancient Maya civilization through his meticulous and innovative field methods in the late 19th century that included systematic documentation, photography (dry plate), plaster and molds and detailed surveys and plans.

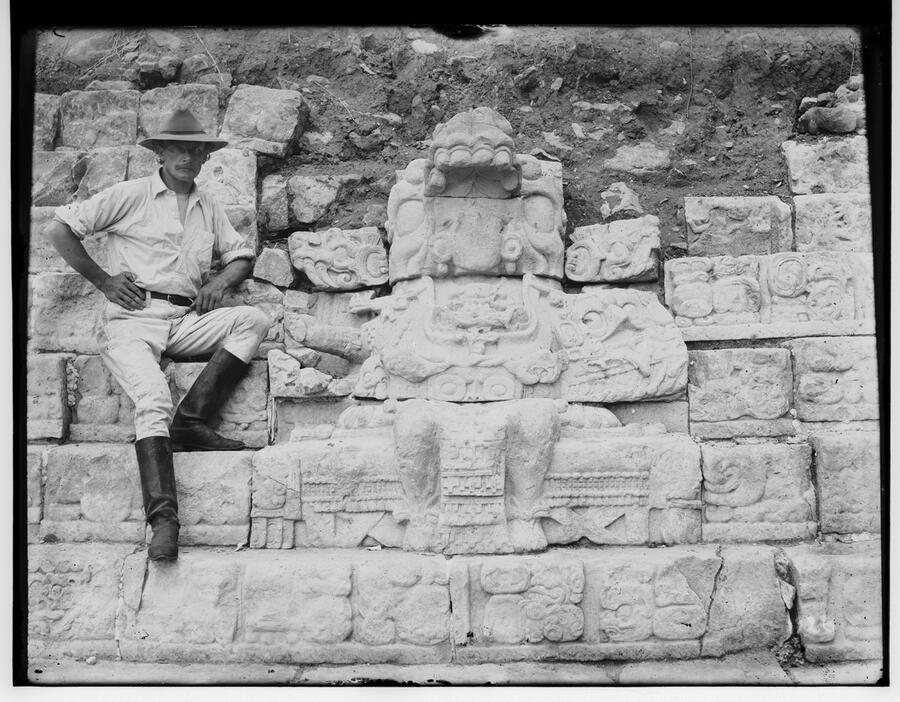

Here he is hard at work:

And he really did work very hard… the Peabody Museum has 750 Plaster Casts, many made by him and his assistants.

Here he is with a partially buried Stela. Copán 1880-1902 Plate 100:

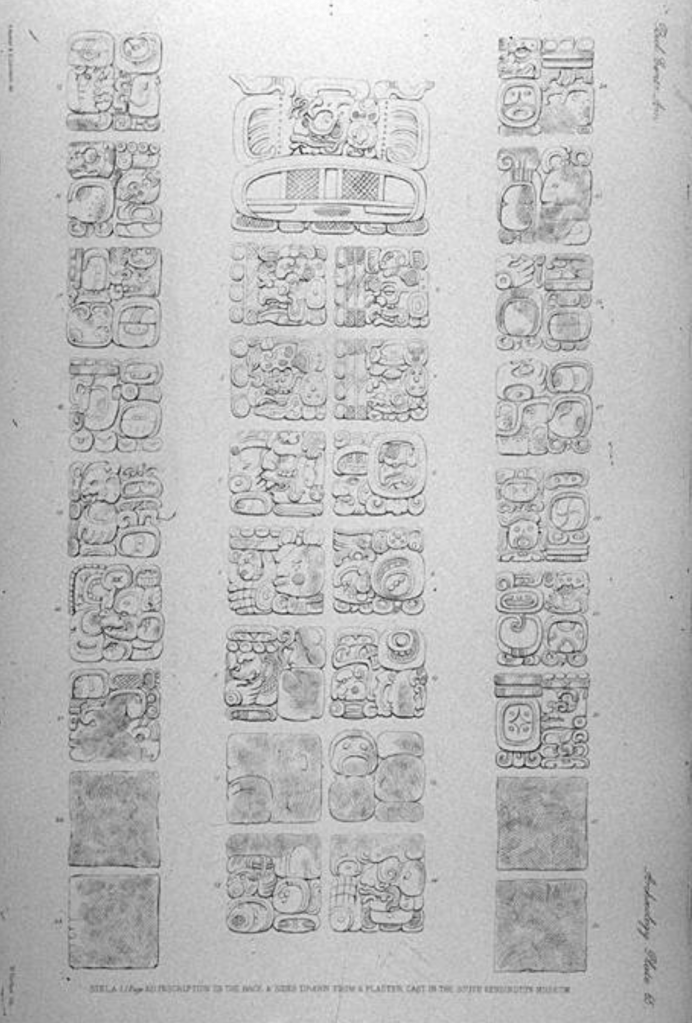

This is a plaster cast of Stela 1 from one of his molds:

And here are the detailed photos and drawings about it in his book: “Biologia Centrali-Americana: Archaeology”. It was a five-volume compendium that meticulously documented his findings. This work set a new standard for archaeological reporting with its accuracy and attention to detail. If you are interested you can see it HERE. It is astounding!

He did not do the drawings! He hired very skilled artists to translate the images from his photographs. The most prominent artist credited for the lithographic plates (the primary method of reproduction for many of the drawings) in his Archaeology volumes was Annie Hunter. She committed many years to the work, meticulously translating Maudslay’s photographs and his plaster/paper molds into detailed line drawings.

Now what is on this Stela. Ready?

Stela 1 at Copan depicts Smoke Imix God K, the 12th ruler of Copan. He is also known as Smoke Jaguar. His full deciphered name: K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil. Epigraphic analysis (the study of the hieroglyphs) dates Stela 1 to 9.11.15.0.0 4 Ahau 13 Mol, which corresponds to July 28, 667 CE.

He was a crucial figure in the long-ruling Yax K’uk’ Mo’ dynasty of Copán, succeeding K’ak’ Chan Yopaat.

Smoke Imix God K had an exceptionally long reign, from 628 to 695 CE, ruling for 67 years. This made him one of the longest-lived and most stable rulers in Copán’s history. His longevity is even highlighted on Altar Q, where his long reign is symbolized by a “5 k’atun” glyph, rather than a depiction of him sitting on his name glyph.

During his rule, Copán experienced a period of stability and growth. He was known for placing stelae not just within the city’s main ceremonial core, but also at the edges of the Copán Valley.This suggests a strategic effort to consolidate his power and mark the extent of Copán’s influence throughout the region.

He was the father of Waxaklajuun Ub’aah K’awiil, better known as 18-Rabbit, who would become the 13th ruler and perhaps the most famous and artistically prolific king of Copán.

Smoke Imix God K died at the impressive age of 90 (Me: WOW!!!) and was buried in a tomb within Structure 10L-26, which his successor (18-Rabbit) would later elaborate with the first version of the Hieroglyphic Stairway.

Here is a description of each side:

West Side (Front): This is the figural side, depicting Smoke Imix God K himself. He is shown in a turban-like headdress and wears large earflares, a tubular collar, a feathered cape, and a pectoral. He is depicted clenching a double-headed serpent bar against his chest, a common symbol of Maya kingship and ritual authority. The carving is in the typical Copán high-relief style, though scholars note Stela 1 marks a turning point towards even greater three-dimensionality compared to earlier Copán sculptures.

East Side: This side is entirely glyphic, containing the important hieroglyphic texts that provide the monument’s date and likely other historical or ritual information.

North and South Sides: These sides feature long vertical columns of glyphs adjacent to the east side, with profiles of the ruler’s figure next to the front (west) side.

Aside who it is about and the date of this ruler’s time frame we still don’t know completely what the hieroglyphics say.

So fascinating huh? It was so great to see more in detail some of the many artifacts I saw at this exhibit. I will share a few more photos but sadly I don’t have any more time to go into detail:

^ ^ Thank you Harvard University for your detailed and deep studies in archeology… and preserving those 750+ plaster casts where sculptural art and hieroglyphic writing from monuments and buildings at over twenty-five archaeological sites in Mesoamerica is stored for posterity and for making some of it available to us, to Alfred P. Maudslay for all your hard work! in preserving our unique and beautiful Pre-Hispanic culture and you dear reader for coming along! Today is 4th of July and that in Maya years this would be: 13.0.12.12.18

May the Fourth be with us!