The origins of La Guelaguetza are deeply rooted in the history of the Zapotec and Mixtec peoples of Oaxaca.

The word “Guelaguetza” comes from the Zapotec language and means “reciprocal exchanges of gifts and services,” a concept of community sharing that is central to the festival. Originally, the celebration was a pre-Hispanic ritual on the Cerro del Fortín to honor Centeótl, the goddess of corn, and ensure a good harvest.

After the Spanish conquest, the festival was moved to coincide with the feast of the Virgin of Mount Carmel in July. This led to a blending of indigenous rituals with Catholic traditions. The modern festival, which officially began in 1932, was created to celebrate the cultural diversity of Oaxaca and to promote unity.

La Guelaguetza is a spectacular cultural event that includes various presentations, markets during the day and night but the highlight of the Guelaguetza is the Lunes de Cerro, which take place the last two Mondays of July. Each Lunes de Cerro presentation is a display of the customs and traditions of 16 communities across all 8 regions of the state of Oaxaca, on the Auditorium stage. At the end of each performance, they throw gifts from their region into the crowd, keeping the ancient spirit of sharing and reciprocity alive.

I had the fortune of seeing the Lunes de Cerro during my first and only trip to Mexico in the year 2000. We didn’t even know about this festival and I read about it as I was looking for things to do in our next destination Oaxaca. So we got our tickets and made slight changes in our plans to make it there. It was so worth it!

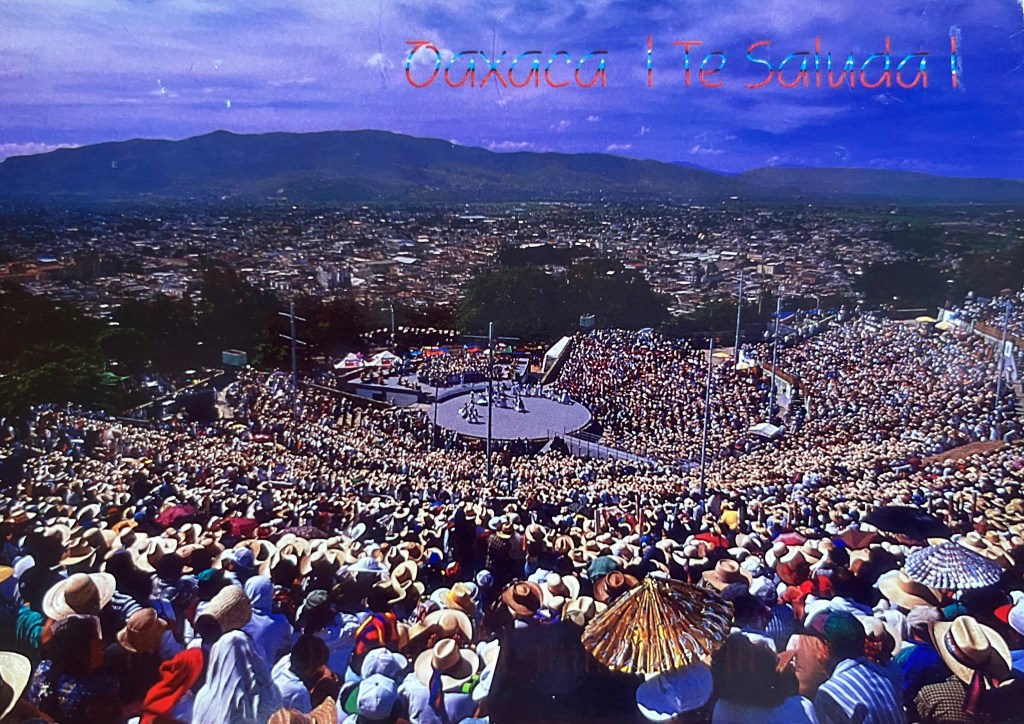

One entered a huge festival ground with a round stage with a band area set up in one side. There was also an image of the “Virgen del Mount Carmel” to which each delegation would stop and honor with an offering of their harvest and creations.

The following is a postcard I picked up when I went, notice it does not have any tent…

We were very lucky as a man in charge of directing people inside gave us seats right behind the press! (The venue was already pretty full as we arrived way too late!) These are some of my photos mixed with some postcards I bought at the time. By the way some of my photos say 94… that’s because I had my camera set to the wrong date. I also will enrich it with some photos and videos from the internet. (The colors of my photos are not as bright as they were taken way back and with a roll! No digital photography back then!)

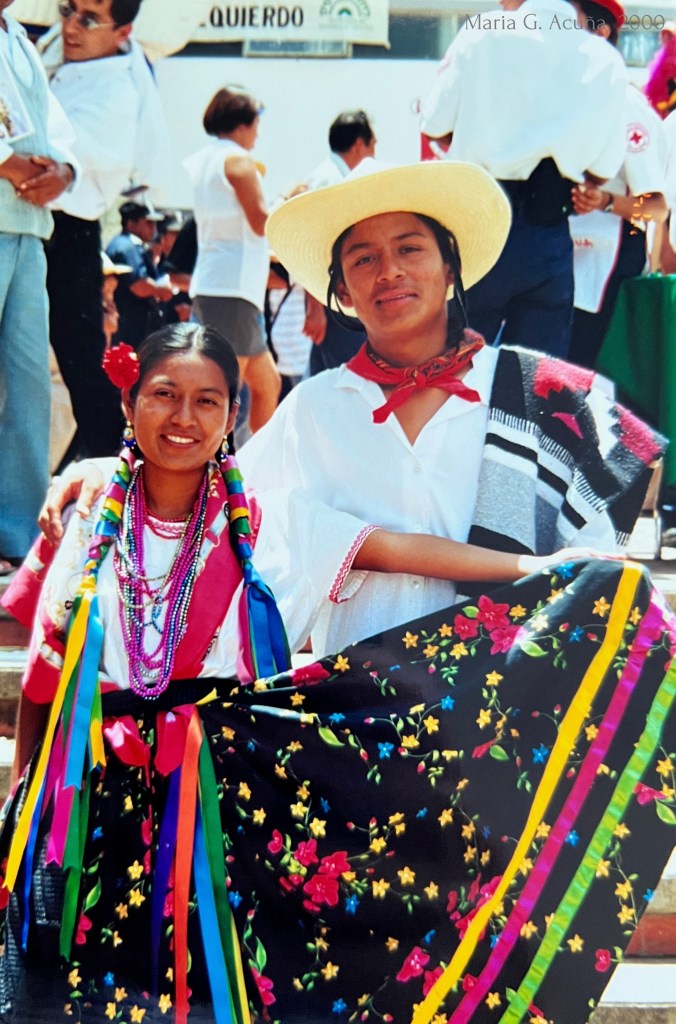

I wanted to show the brightness of the colors of their dresses so I found this photo in the internet:

Aren’t their dresses incredible… hand embroidered!

I found a video from this part …from the year 2000!

And I took a phot of the first couple that appears in the video after the performances as they all hang around afterwards for photos and celebration! ^ ^

Yeah… that’s crazy me with the double hat! I was an honorary pineapple dancer! ^ ^

The last act was incredible… this is “La Danza de las Plumas” (The feather Dance):

Origin of La Danza de la Pluma

La Danza de la Pluma is a traditional Mexican dance from the state of Oaxaca. Its origins trace back to the 1700s, blending indigenous Zapotec and Aztec traditions with the influences of the Spanish Conquest. It is believed that Spanish friars created the dance to help evangelize indigenous people, adapting pre-Hispanic dances to tell a theatrical story. The dance is a central part of local Catholic festivals and patron saint celebrations.

Meaning and Significance

The dance is a powerful, symbolic reenactment of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. The performance tells the story of the encounter between Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II. The elaborate choreography and music, often lasting for days, depict historical events and serve as a form of cultural preservation.

Key elements include:

Syncretism: The dance is a prime example of two cultures blending, as it uses a Spanish dramatic form to tell a story from an indigenous perspective.

Symbolism: The dancers wear a towering headdress (penacho) made of colorful feathers, which gives the dance its name and symbolizes the celestial sky.

Cultural Preservation: For many communities, performing this dance is a vital way to honor their heritage and reflect on the historical trauma of the conquest, celebrating the resilience and fusion of two cultures.

It was so great to relive this experience and learn a bit more about this incredible festival. Two other things I remember were:

Some of these indigenous groups were very proud of the fact that the Spanish never conquered them as they lived in the mountains (and you could hear they all start their presentations in their indigenous languages).

And the second is that even though you can’t see it, every group shares their harvest and creations not only with the virgin but with the crowd! They throw all sorts of things into the crowd! I got a bag full of all kinds of fruits, vegetables and creations. I was a bit horrified when they threw coconuts, pineapples and ceramic bottles full of alcoholic drinks all handmade!!! They point at you and show you what they will throw and that’s how I got the pineapple! There was only one person that got hit in the head that I noticed… it was so exciting and dangerous!

As I researched about the Guelaguetza I found some information about the history of the festival and how it has changed through time. Many people have criticized it as it has become too commercialized and lost its original intent… here is a short history in you are interested in this part:

The Guelaguetza festival, a cornerstone of Oaxacan culture, has a history marked by significant shifts from its indigenous roots to its modern form. Its evolution reflects the broader history of Mexico, including the Spanish Conquest, nation-building, and the pressures of globalization and tourism.

From Indigenous Ritual to Modern Festival

Pre-Hispanic Origins: The word “Guelaguetza” comes from the Zapotec word for “reciprocal exchange” or “mutual cooperation.” Originally, the festival was an indigenous ritual dedicated to Centeótl, the Aztec goddess of maize, and was held on a hill known as the Cerro del Fortín. It was a time for communities to come together, give thanks for the harvest, and exchange gifts and services.

Colonial Adaptation: After the Spanish Conquest, the Catholic Church assimilated this celebration by linking it to the feast of the Virgin of Mount Carmel, celebrated on July 16th. This act of syncretism allowed indigenous people to continue their traditions under the guise of a Catholic festival. This is why the modern festival is still known as “Lunes del Cerro” (Mondays on the Hill).

The 20th Century: Commercialization and State Control: The most significant changes occurred in the 20th century. In 1932, following a devastating earthquake, the state government of Oaxaca reorganized the festival as a major cultural event to boost morale and promote tourism. It was at this time that the event began to be called “Homenaje Racial” (Racial Homage) and started to take on a more theatrical, staged format, with delegations from different regions of Oaxaca performing their representative dances.

Rise of the Tourist Spectacle: In 1974, to accommodate growing crowds, a large, modern amphitheater was built on the Cerro del Fortín. The festival became highly commercialized, with tickets being sold at prices that were often out of reach for many local, indigenous people. This shift transformed the event from a community-based ritual into a spectacle aimed at national and international tourists, leading to accusations of cultural exploitation.

Political and Social Responses

The “Guelaguetza Popular”: The commercialization of the official Guelaguetza led to significant protest. In 2006, during a major teachers’ strike and social unrest, a parallel festival known as the “Guelaguetza Popular” was created. This alternative event, organized by social movements and indigenous groups, was free to the public and aimed to reclaim the original spirit of reciprocity and community. It was a direct response to the official festival’s commercialism and its use as a tool for government political agendas.

Recent Changes: In recent years, there have been efforts to address some of the criticisms. For example, some government changes in the selection of participants have aimed to make the official Guelaguetza more inclusive of communities that had been previously excluded. The festival also continues to be a platform for political expression and a symbol of indigenous identity and resistance, even as it serves as a major tourist attraction.

In summary, the Guelaguetza has transformed from a local, reciprocal system of exchange into a large-scale, state-sponsored cultural festival. While this has brought global recognition and economic benefits, it has also sparked controversy and a parallel movement to preserve the festival’s original, deeply communal meaning.

I really hope they can find a balance… we can’t expect things to stay exactly the same… it is unrealistic as the demands to see it are higher. I think tourism is really affecting many people in the world and we are in the process of adapting and learning what we can do to limit the excess of people, care for the original creation/culture and ultimately preserve it. We all need to do our part…