Imagine yourself a woman in 1940’s in Europe and wanting to be an artist. The place was way too oppressing with the war and its aftermath and also with the fact that art was dominated by men. Women were only seen as muses. So … a few women decide in their different situations to immigrate to Mexico.

The result was the Mexican Surrealist Woman’s Movement, where women artists explored personal experiences to challenge the male-dominated Surrealist European movement, which traditionally objectified women. They went on to create powerful, self-affirming art focused on the feminine subconscious, spirituality, and themes of magic, mythology, and the female body as a site of power. Their diverse works included paintings and writing, and they were also active in the Mexican Women’s Liberation Movement.

Let’s meet some of these women:

Frida Kahlo (Mexican). Considered the most famous female Surrealist (and artist?), her unique work explored identity and suffering through personal trauma.

Remedios Varo (Spanish-born, lived most of her life in Mexico). Her luminous works explored the inner lives of women, blending nature and science with themes of spirituality and magic.

Leonora Carrington (British-born, naturalized Mexican). She is known for her fairy-tale-like paintings and writing, filled with animal/human hybrids and goddesses, and she was a founding member of Mexico’s Women’s Liberation Movement.

Alice Rahon (French born, naturalized Mexican). A painter and poet, her work was notably influenced by indigenous Mexican art and pre-Columbian styles.

Kati Horna (Hungarian-born, naturalized Mexican). Her later work frequently featured themes of domesticity, magic, and the uncanny, often using masks and dolls to explore deeper emotional and psychological states.

Let’s float into the incredible world of the first three… ready?

Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón (de Rivera), Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was a prominent Mexican artist renowned for her vivid and deeply personal self-portraits. Her life was greatly defined by physical and emotional pain, which she courageously transformed into her art. At six, she contracted polio, leaving her with a lasting disability, and a devastating bus accident at eighteen caused lifelong injuries and the need for more than 30 surgeries. It was during her lengthy recovery that Kahlo began to paint while confined to her bed.

Her art, though often linked to Surrealism (she denied it), was a raw and honest exploration of her experiences, from chronic pain and her tumultuous relationship with her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, to miscarriages. She incorporated vibrant colors and rich symbolism from Mexican folk art and indigenous cultures into her paintings. A dedicated communist and a fierce advocate for Mexican identity, Kahlo is now remembered as a master artist, a feminist, and a cultural icon whose unwavering self-expression continues to resonate worldwide.

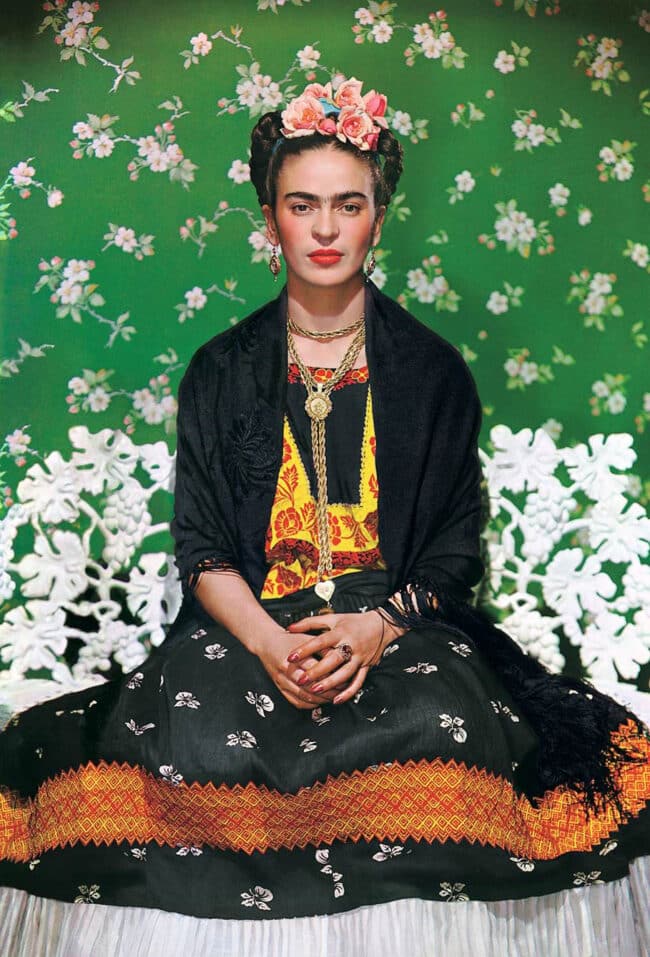

And my favorite photo of her:

This great photographer was in a relationship with her for 10 years (on and off).

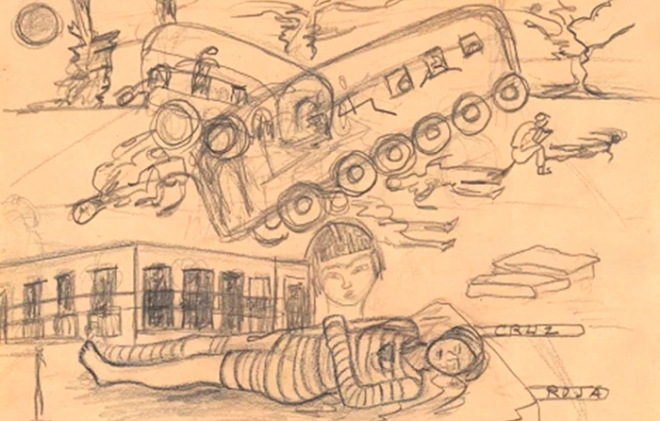

Almost 100 years ago, on September 17 of 1925, Frida suffered her terrible accident. This is the only art she ever created about it, a sketch:

It is a miracle that she was able to paint this a year after… when one considers the severity of her injuries. She was so strong!

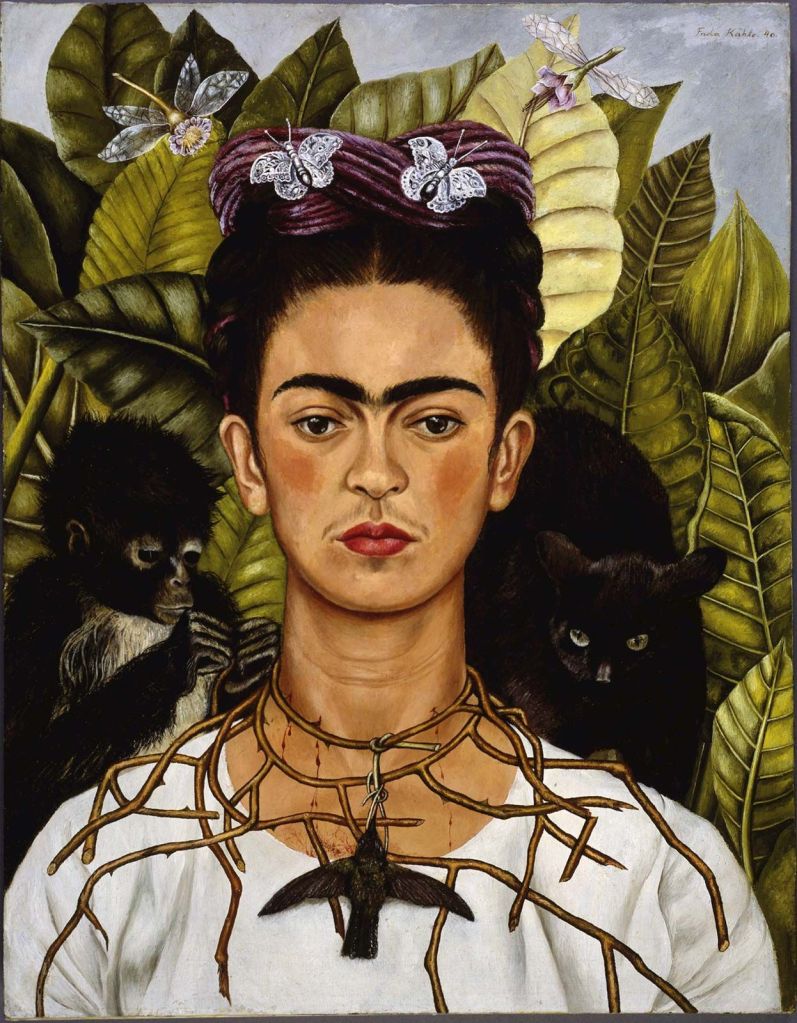

This double self-portrait by Frida Kahlo depicting two versions of herself sitting side-by-side was painted shortly after her divorce from Diego Rivera.

The most prominent symbolism is the two versions of Kahlo herself. They represent two conflicting sides of her identity, particularly in relation to her husband, Diego Rivera.

The European Frida: On the left, this figure wears a white, European-style Victorian dress. Her heart is torn and bleeding, symbolizing the pain of her heartbreak and the part of herself that Rivera had rejected. She holds a pair of surgical forceps, attempting to stop the bleeding, a futile action that underscores her emotional and physical suffering.

The Mexican Frida: On the right, this figure wears a traditional Tehuana dress, a style Rivera loved and which symbolizes Kahlo’s deep connection to her Mexican heritage and her pride in it. Her heart is whole, representing the part of her that was loved and complete with Rivera. She holds a small portrait of Rivera as a child.

In spite of all those nails that symbolize the constant pain that she is in, her pupils have the shape of white doves… a symbol that she has hope.

This is a painting at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston…

I also saw an exhibit of her work at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, but I was not able to take photos… as it was not allowed. So I only have these from the entrance and the store:

To see more of her incredible and unforgettable work, go HERE… 163 paintings!

Remedios Varo

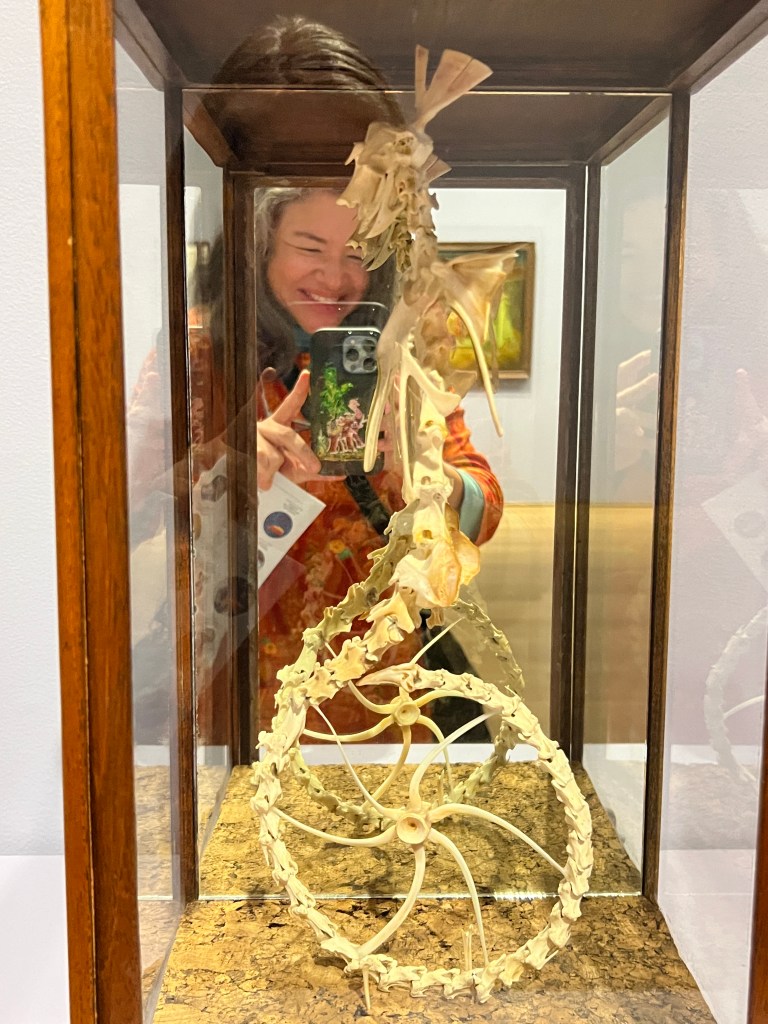

I discovered Remedios Varo about 5 years ago. I went to a conference in Washington D.C. and my colleague and I had the chance to visit the Women’s Museum. I will never forget it because I only saw one of her paintings and I could not stop looking at it… I kept asking myself… how could I not know you existed?

Then destiny brought her to my life again… this time a full exhibit when I went to another conference in Chicago. I was elated! I delighted in every brush stroke… in the symbolism of every painting… and I bought the exhibit book (which I rarely do)… but her paintings touch something in me to the point of becoming after this exhibit my favorite female painter… (very closely followed by Frida Kahlo).

And just about two weeks ago I saw a painting of hers right in my hometown… acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston. They got it in 2022… and I just found out about it this year! One I had never seen before. So now I will share it all with you as I fully documented it! ^ ^

First let me tell you a bit about her life…

Remedios Varo (1908–1963) was a Spanish-born Surrealist painter who became a central figure in the Mexican art scene. Fleeing Europe due to the Spanish Civil War and World War II, she settled in Mexico in 1941, where she developed her distinct artistic style and forged close friendships with other exiled artists, most notably Leonora Carrington and Kati Horna.

Some may argue that she is not Mexican and how come I have placed her here. Even though she did naturalize as Mexican, she developed her artistry in Mexico.

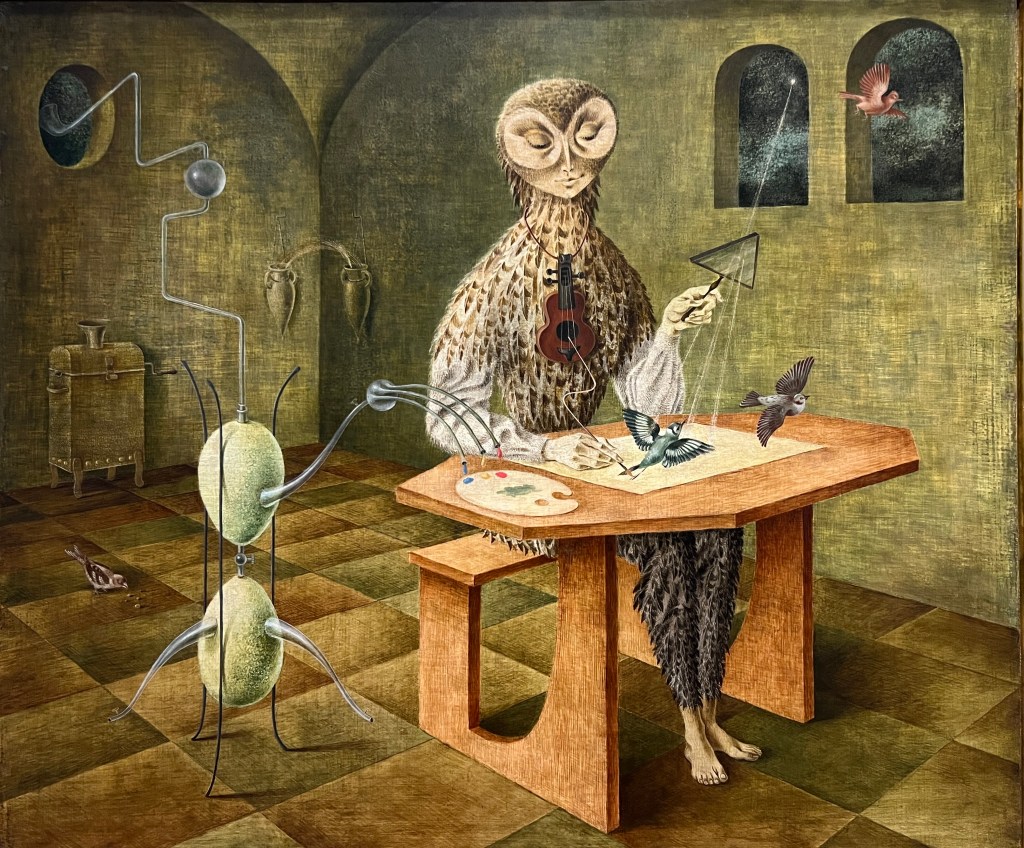

Varo’s style is distinguished by its meticulous, detailed craftsmanship, a skill she developed while observing her father, a hydraulic engineer. This technical precision imbues her fantastical, dreamlike scenes with an almost photographic clarity, drawing comparisons to early masters like Hieronymus Bosch. Her paintings are populated by androgynous figures, often resembling herself, who are shown undertaking mystical, alchemical, or scientific pursuits in otherworldly environments.

Her work is rich with profound symbolism, addressing themes such as:

Alchemy and the Occult: Driven by a deep interest in esoteric philosophies, Varo’s canvases frequently show her characters performing magical rituals or creating life through strange, transformative processes.

A Fusion of Science and Nature: She masterfully combined elements of the natural world with scientific instruments and mechanical objects, creating bizarre hybrid creatures and fantastical machines.

Empowering Female Narratives: In stark contrast to the male-dominated Surrealist movement, which often objectified women, Varo’s art portrays her female subjects as powerful creators, explorers, and thinkers. They actively navigate their own destinies and break free from confinement.

Exile and Journey: As a refugee, themes of displacement and the search for a spiritual or physical home are central to her work. Her characters often appear to be on a quest, journeying through surreal landscapes in precarious, dream-like vehicles.

Following a major solo exhibition in Mexico in 1956, Varo’s work achieved widespread acclaim, solidifying her legacy as one of the most important Surrealist painters of the 20th century.

To start I will show you the first painting I saw of her that absolutely captivated me:

I think she plays with the word llamada, as llama aside from the animal also means flame.

I forgot to take a photo of the description so now I assumed it related to the trenches in a war… dead men trapped and the figure in orange like an angel. Now reading about it … I was wrong! The painting’s title itself refers to a divine or inner calling. The protagonist is responding to this summons, leaving behind a world of conformity and embracing a path of mystical knowledge and self-discovery. And she also empowers the female figure, who is not a passive object but an active agent. She is an allegory for the woman artist or thinker who must break free from societal constraints to pursue her creative and spiritual mission. WOW!!!

I also read that she painted this two years before her death… when she has mastered her unique style.

These are my photos of her paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago:

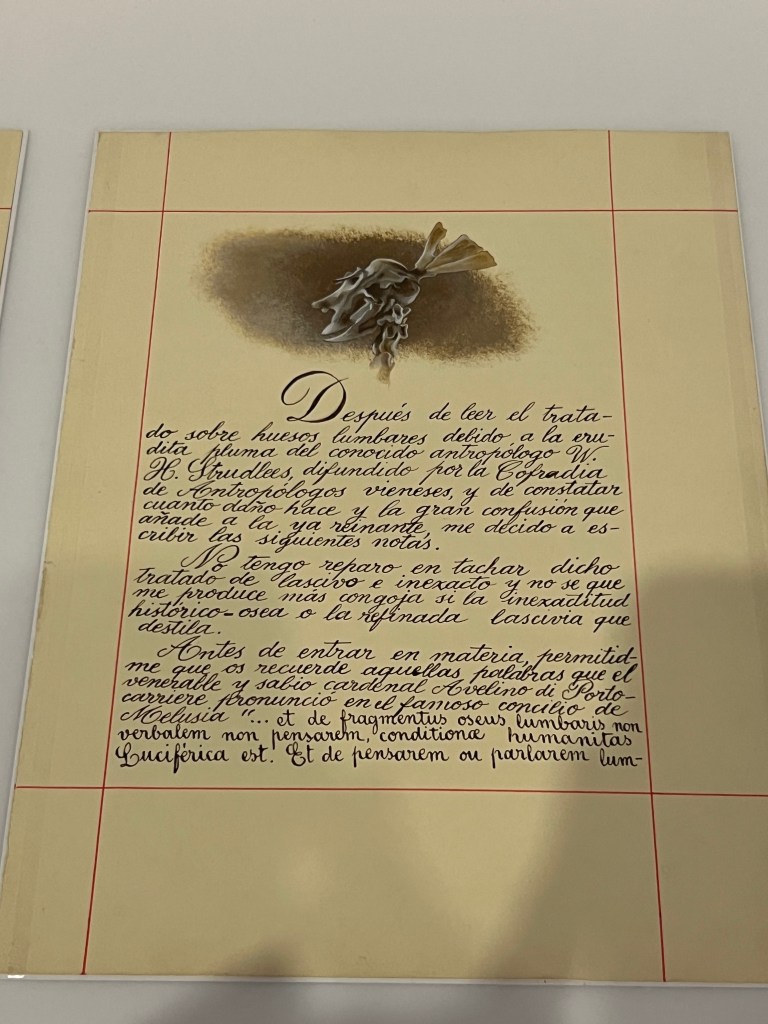

I will showcase a lot of her paintings here as some can’t even be found in the internet! and I will add one of their descriptions. It is SO fascinating to read about her paintings! She adds so much detail and meaning.

Did you notice the cat?! The more I see it, the more I find! I never get tired of looking at her paintings!

I identify a lot with the vagabond. As I am getting older and looking to my future… I feel I will be like this figure… carrying all my belongings with me wherever I end up… because I want to travel when I retire and live in different countries. Will I have the guts? Only time will tell! But I want to! If I could find a vehicle like that that flew… I’d be all set! ^ ^

I adore how she mixes objects and backgrounds into her figures! And she really takes care of the tailor/clothing aspects…

And this one is one of my favorites:

It is so incredible… is it not?!

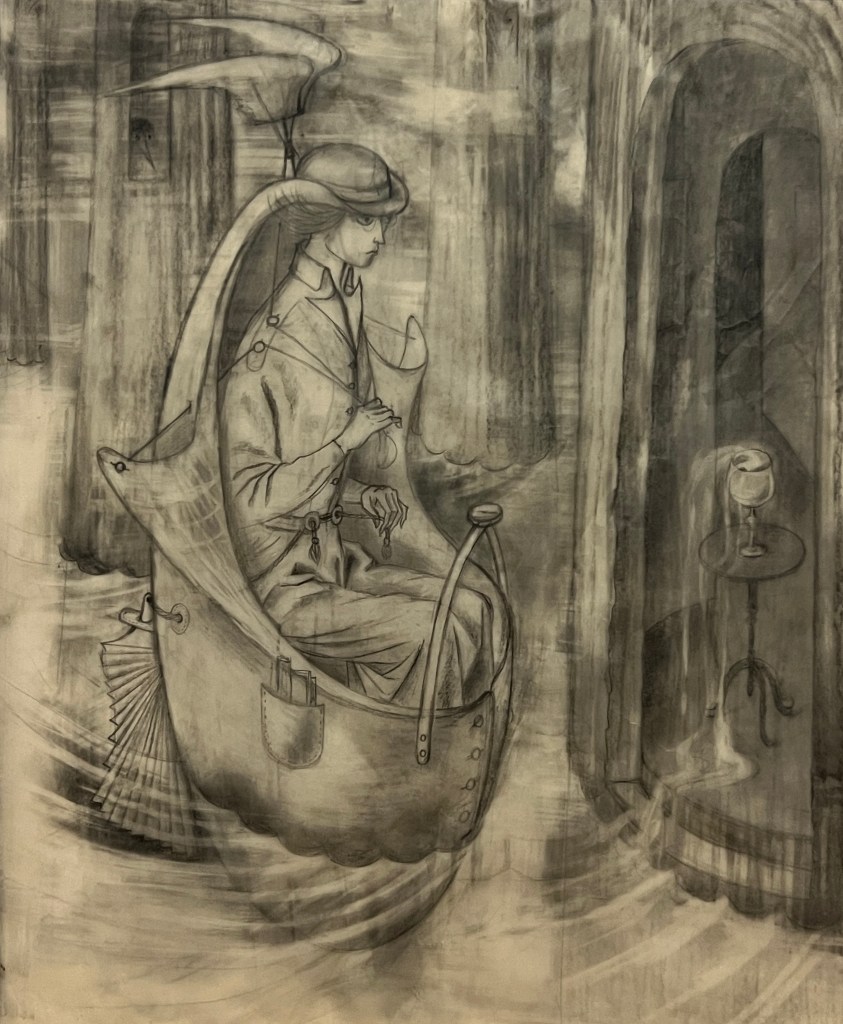

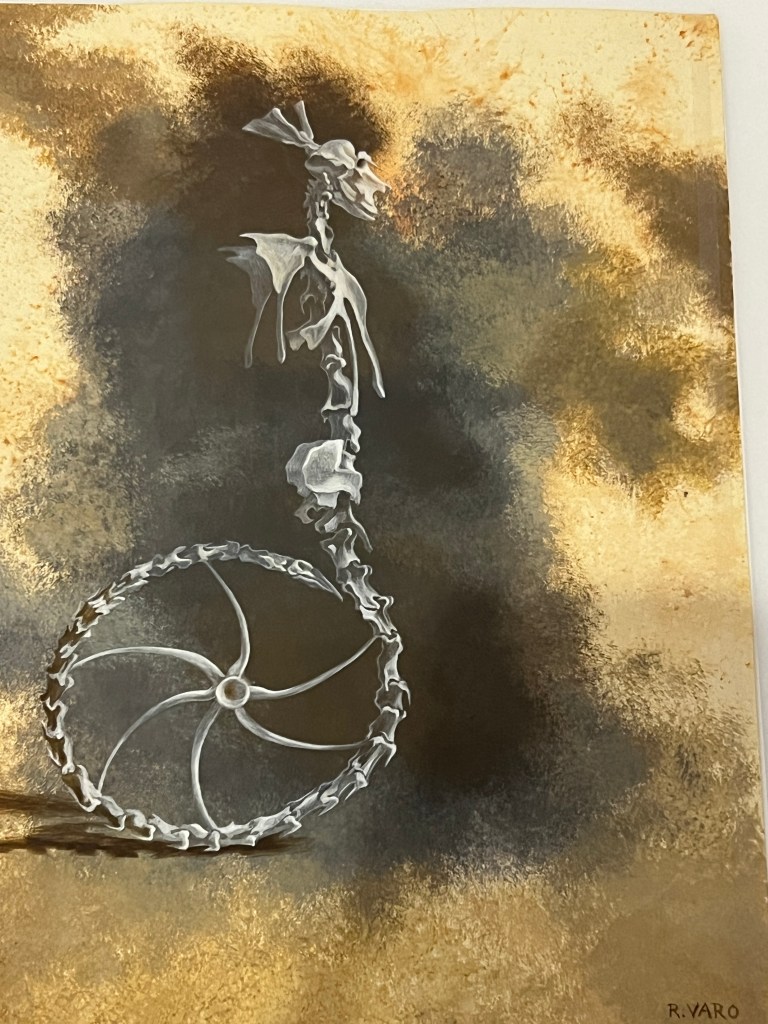

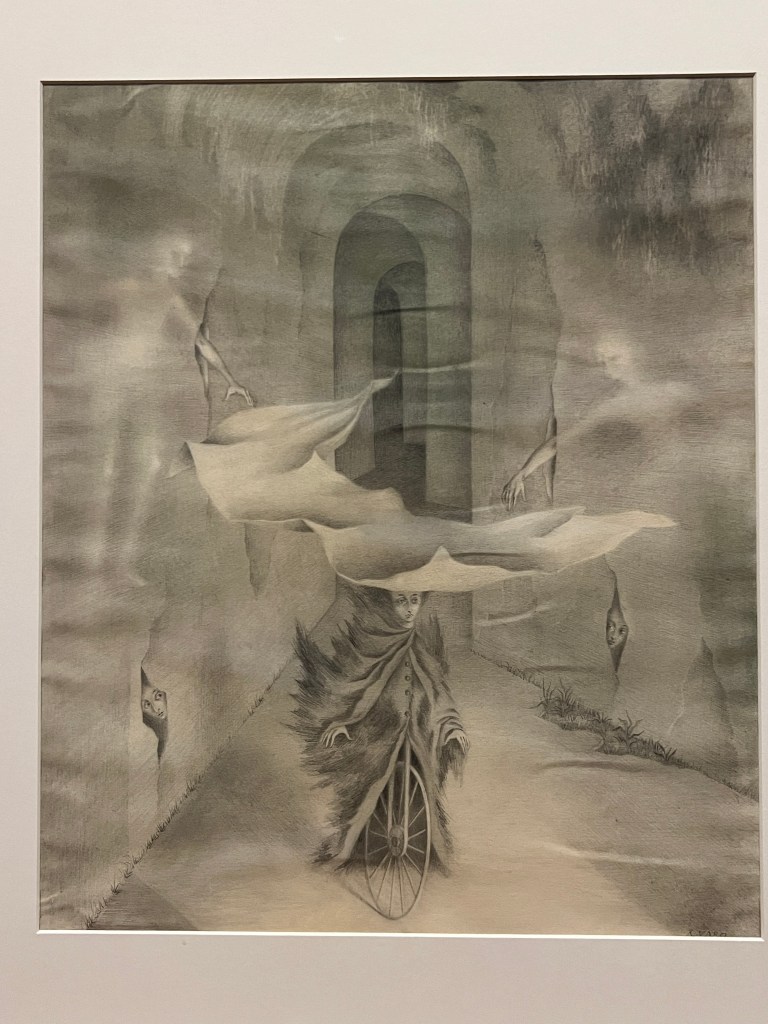

I was so impressed with the quality of her sketches! Almost a black and white version of the color painting!

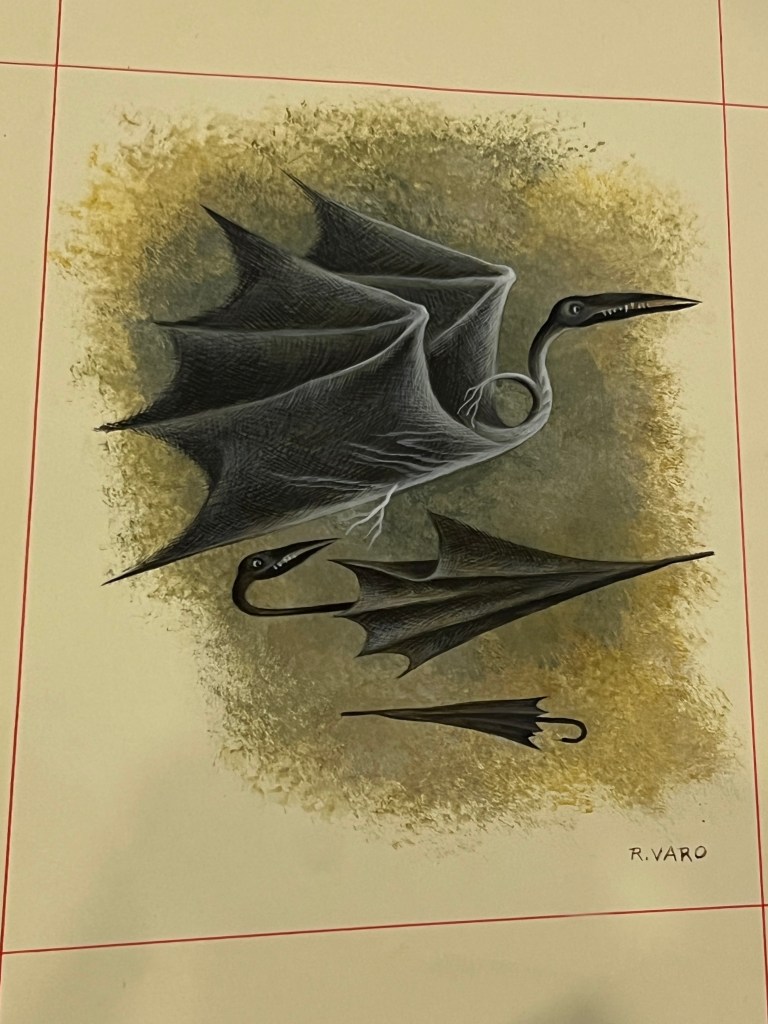

This umbrella pterodactyl absolutely blew me away… !!!

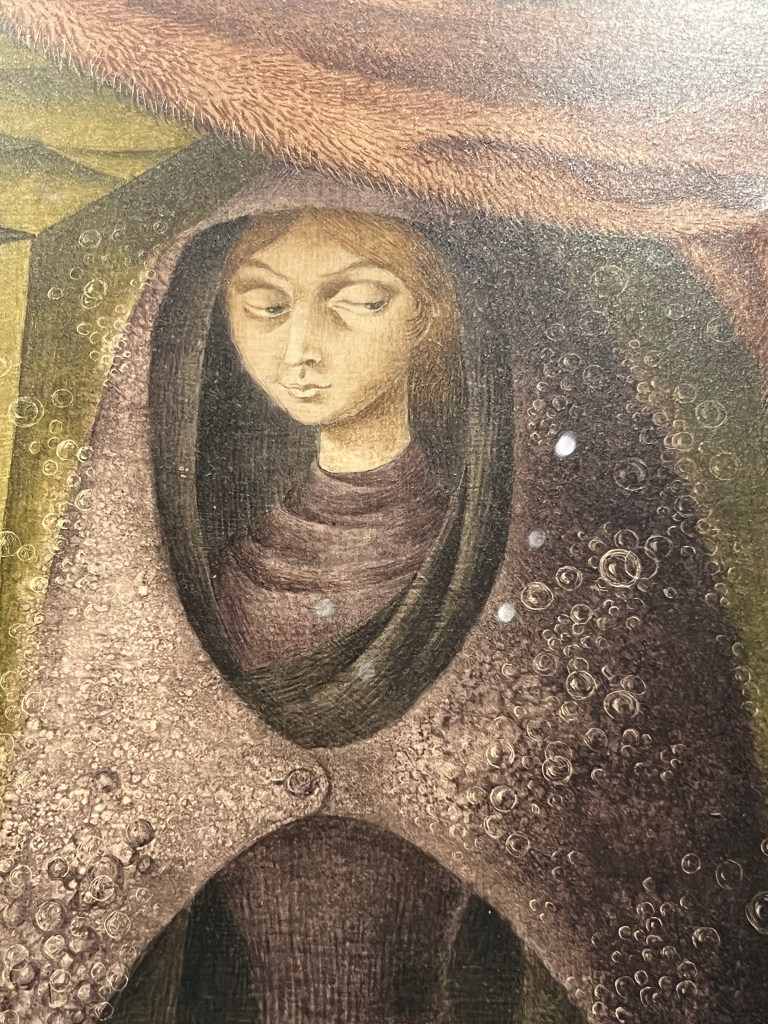

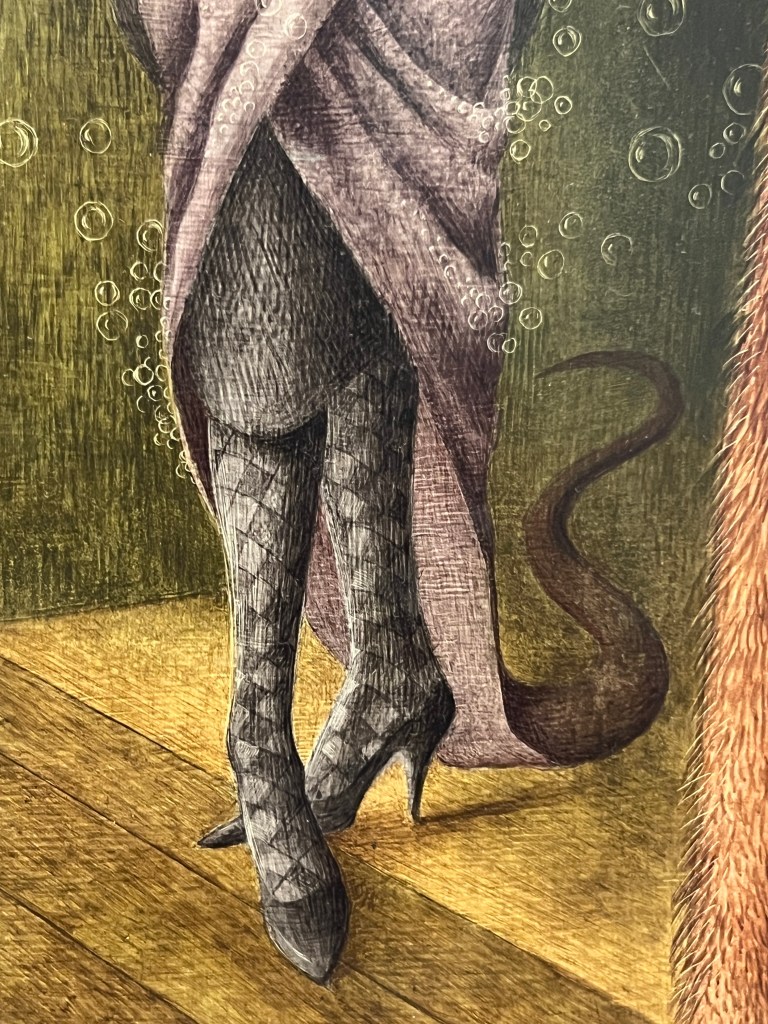

Last, here is the painting I saw recently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I have to mention that this is one of her largest paintings so one can really see high detail in every character.

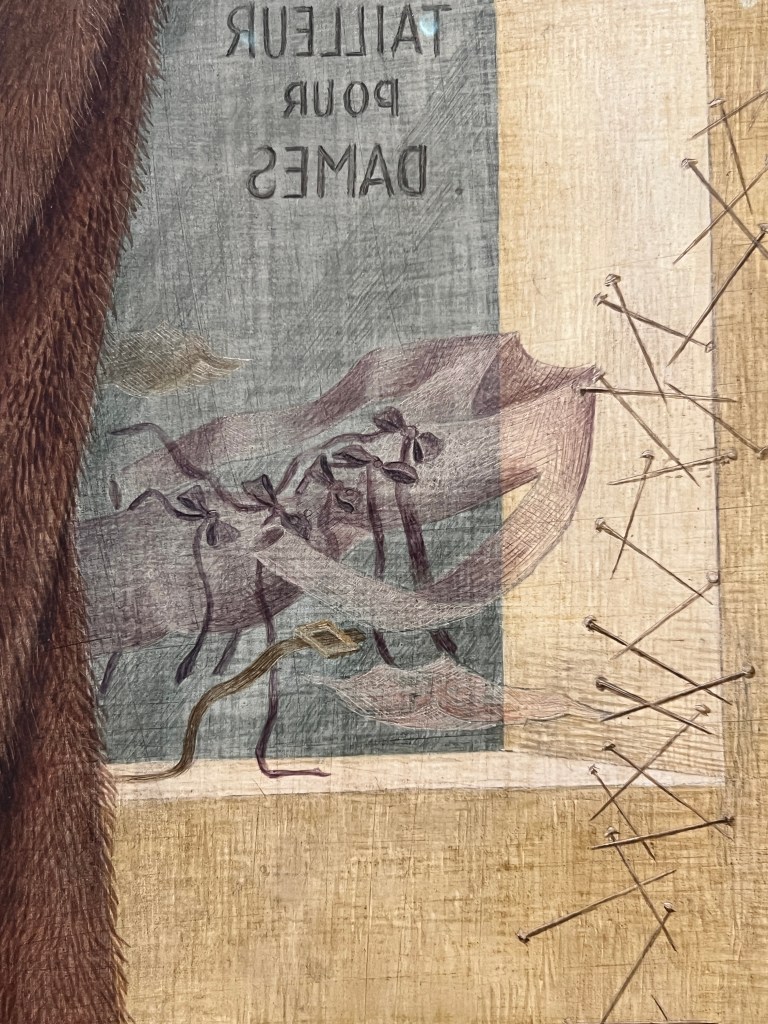

Tailleur pour dames (“Ladies’ Tailor”) Remedios Varo, 1957.

The scene is a bizarre, theatrical tailor’s showroom where a client’s choice of garment becomes a metaphysical act. The garments themselves possess magical qualities: a rose-colored dress becomes a sailboat, a blue scarf transforms into a seat with a tray for cocktails, and a dark cape fabric fizzes like champagne.

The client, according to Varo’s own notes, “splits into two other persons” to represent her indecision and inner turmoil. A figure of the tailor, whose eyeglasses are shaped like scissors, works in the background while a mysterious magnet on the floor attracts pins out of thin air. Through this magical tailoring, Varo illustrates how clothing can be a vehicle for escape or the creation of a new self, reflecting her interest in psychology and the powerful, albeit often unseen, forces that shape identity.

Leonora Carrington

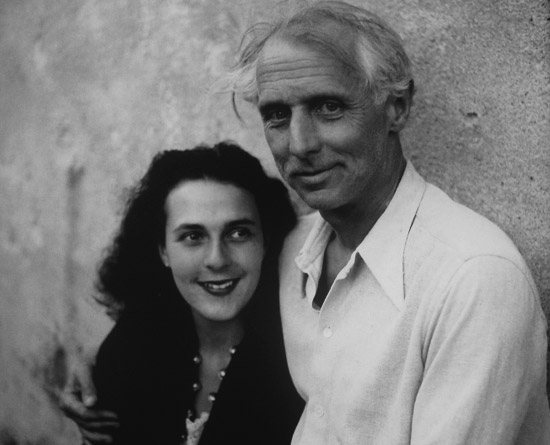

Leonora Carrington ((6 April 1917 – 25 May 2011) was a British-born artist and writer who rose to prominence within the Surrealist movement. She was born to a wealthy English family but rebelled against her strict upbringing, leaving school and eventually pursuing a career in painting. In 1937, her life changed after she met the Surrealist painter Max Ernst. They moved together to France, where she became part of an influential artistic circle that included figures like Salvador Dalí and Pablo Picasso.

The Second World War shattered her world; Ernst was arrested, and she fled to Spain, where she was confined to a psychiatric hospital after suffering a breakdown. This traumatic period became the subject of her poignant memoir, Down Below. After her release, she secured a way to Mexico by marrying a Mexican diplomat and settled in Mexico City in 1942. There, she discovered a supportive artistic community and developed a lifelong friendship with fellow Surrealist, Remedios Varo.

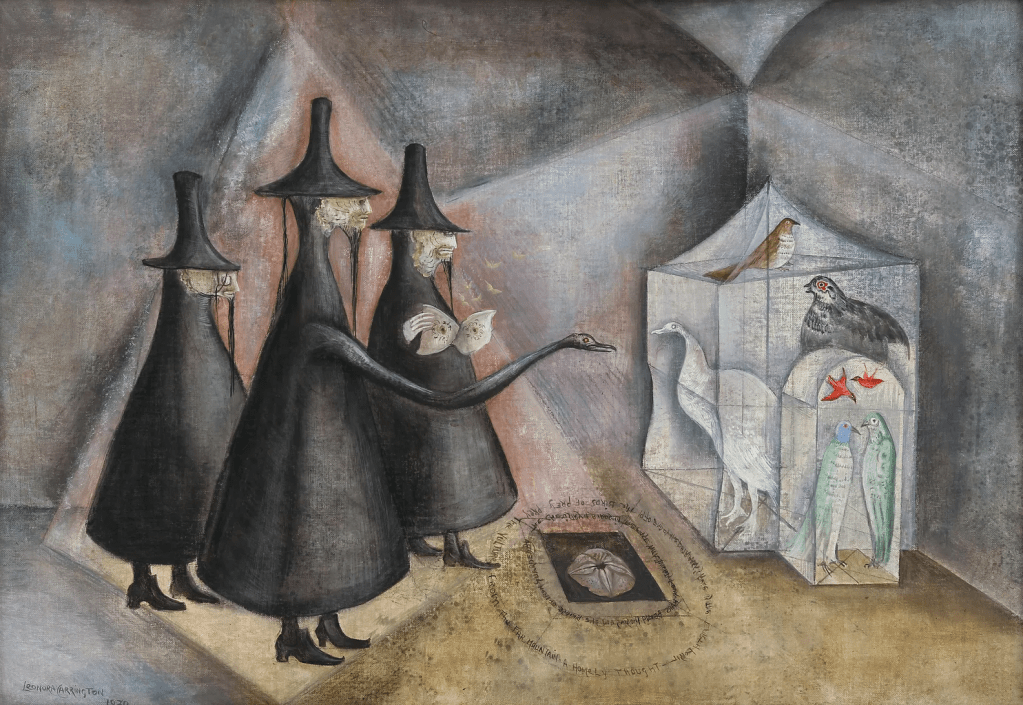

Carrington’s art distinguishes itself through its intricate merging of personal narrative, folklore, and esotericism.

The core motifs in her artwork include:

Feminist and Alchemical Symbolism: Carrington empowered women in her art, challenging conventional roles. She often used animals, such as the hyena and the horse, as alter egos to symbolize her fierce independence.

Mythological Roots: Drawing from her Celtic heritage and a deep fascination with ancient cultures, her works are rich with symbols from folklore and the tradition of alchemy.

Metamorphosis and the Subconscious: She was captivated by the idea of transformation and shifting identities. Her art frequently delves into the subconscious mind, creating a hidden, magical universe that runs parallel to our own.

Now let’s look at her paintings. I really want to see an exhibit of her work. I found it fascinating too!

This self portrait one could say was her manifesto as an artist, in it she showcases her escape from her restrictive upbringing by sitting in a male riding outfit, confronting the viewer. A white rocking horse in the background symbolizes her wild, untamed inner self. A white hyena, her female alter ego, sits at her feet. This imagery represents her rejection of a traditional identity in favor of one that is untamed and surreal.

Leonora Carrington completed the painting, The Meal of Lord Candlestick (1938), shortly after she fled her family in England and began her relationship with Max Ernst. The work captures her rebellious spirit and total rejection of her strict upbringing. The title itself is a scathing reference to her father, whom she nicknamed “Lord Candlestick,” emphasizing her complete dismissal of his patriarchal authority. The painting depicts a horrifying inversion of the Catholic ritual of the Eucharist, where monstrous, gluttonous female figures ravenously devour a male infant lying on a table. The table itself is a detailed representation of the one used in the great banquet hall of her family’s estate, Crookhey Hall. Through this deliberate act of symbolic chaos, Carrington powerfully declares her subversive move toward personal and artistic freedom.

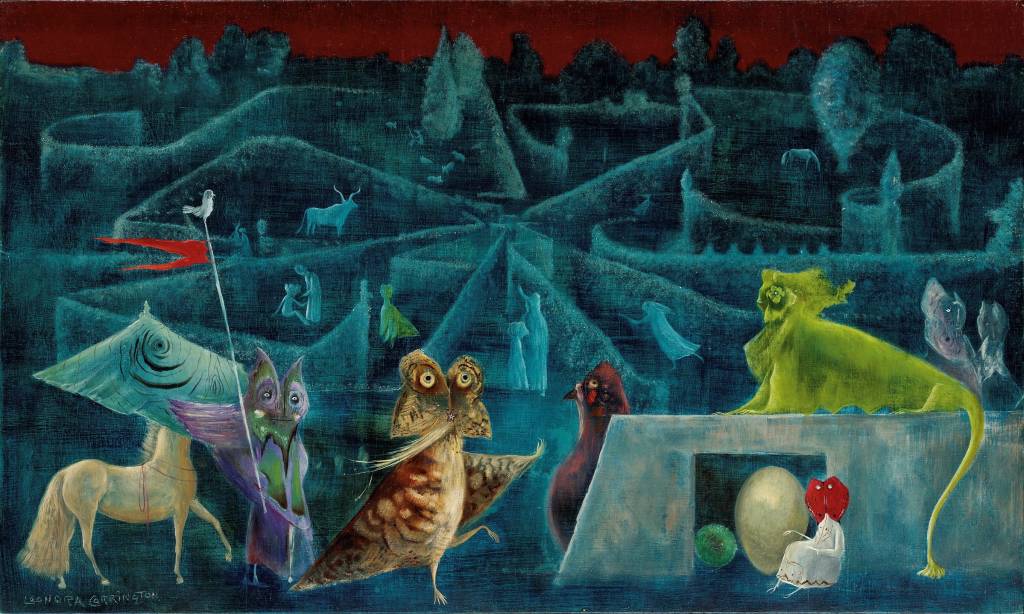

This painting takes its title from the Merovingian dynasty’s seventh-century Frankish King Dagobert I. It is is a critique of patriarchal authority and the failure of rationality. The painting uses a fantastical scene of hybrid creatures and chaotic rituals to symbolize the “distractions” that undermine King Dagobert I’s power and reason. The work is a visual allegory for the subconscious and the supernatural breaking through and subverting the perceived order of the world.

The hybrid creatures that inhabit the painting’s labyrinthine world reflect Leonora Carrington’s fascination with Celtic mythology and the diverse cultural traditions of Mexico. The disconcerting, monstrous figures in the foreground are arranged in a static row, as if performing in a play. At the bottom right, an egg—a symbol of fertility and rebirth—is guarded by a peculiar, red-headed figure. Carrington was deeply concerned with the idea of continuous renewal through self-discovery. This concept is embodied by the shape-shifting figures in the foreground and by the distant creatures searching for a way out of the maze in the background.

Leonora Carrington’s 1953 painting, And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, uses a blend of mythology and magical realism to explore hidden worlds and feminine power. The title’s “Daughter of the Minotaur” is not a monster but a dignified, cow-headed figure in a dress, a symbol of a powerful, all-female lineage that challenges patriarchal myths. The scene, set in a mystical temple, also alludes to alchemical transformation and secret rituals. The presence of two small boys as observers suggests that the viewer is peeking into a magical, inner reality, reinforcing Carrington’s consistent theme of a parallel world accessible through imagination.

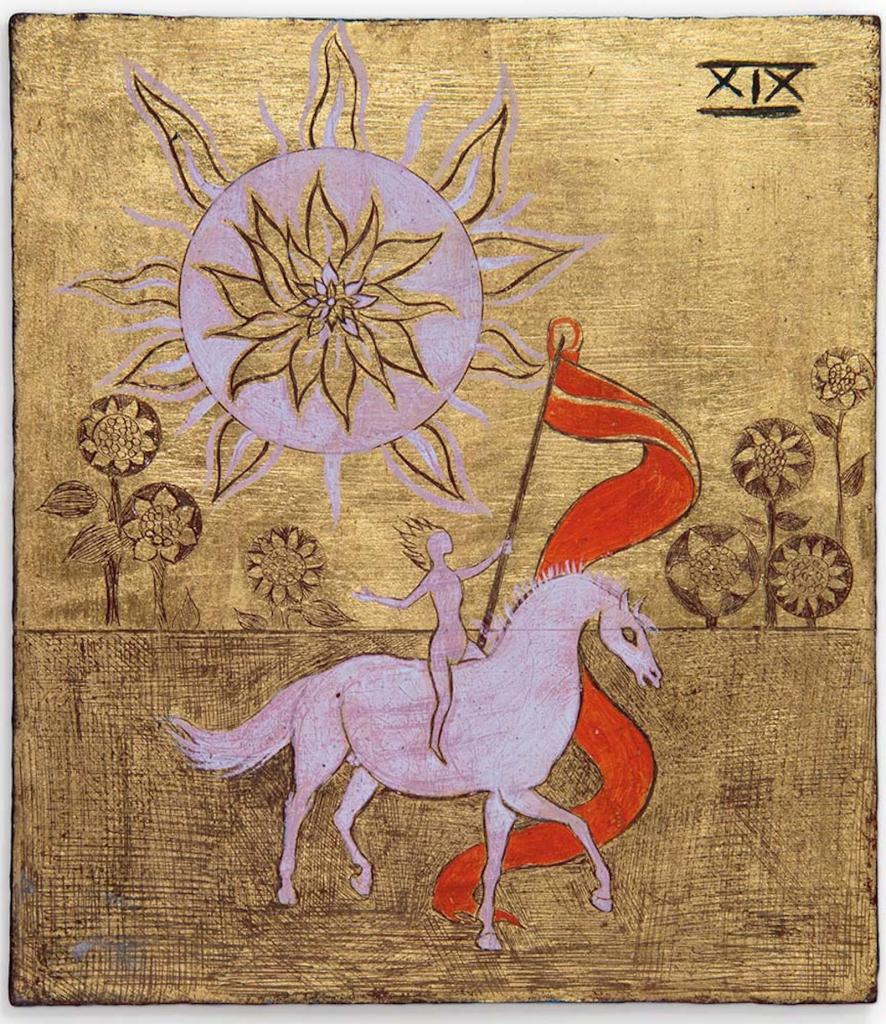

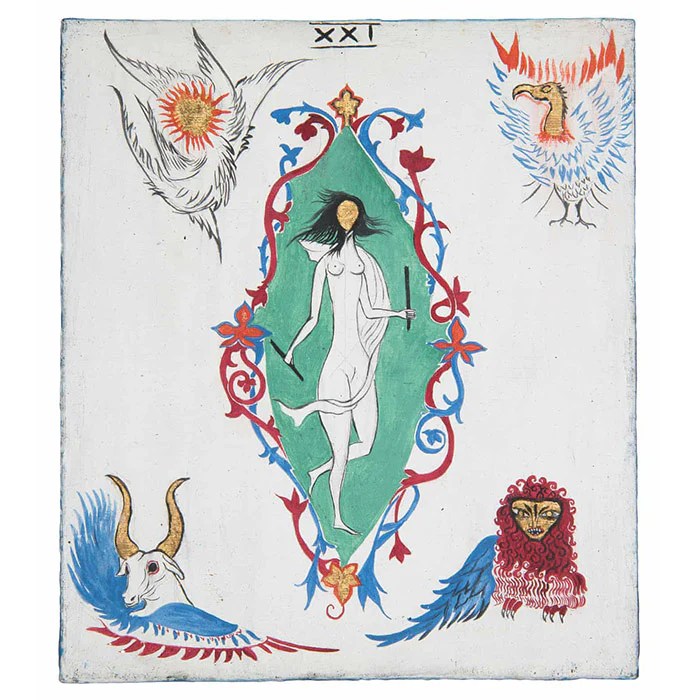

And these are Tarot cards she designed…

And here is the rest…

Last this is the painting at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston… next to Remedios Varo’s one:

One could see how Leonora and Remedios were good friends… they had a lot in common! Their conversations must have been… surreal! And now their paintings are hung next to each other’s… and near by is Frida Kahlo’s too… so their conversations can continue… forever?! How I wish I could be a fly on the wall! ^ ^