The Mexican Muralist movement is widely considered the first major public art movement in the modern world. Unlike earlier murals that often served religious or purely decorative purposes, the Mexican Muralism movement was explicitly born out of a post-revolutionary political and social mission. The government commissioned artists to create art that would educate an often-illiterate populace about national history, cultural heritage, and revolutionary ideals. This was a deliberate use of art as a tool for mass communication and nation-building.

This movement was led by a group of artists often referred to as “Los Tres Grandes” (The Big Three): Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Diego Rivera

Undoubtedly, Diego Rivera is the most famous visual artist from Mexico. Diego and his twin were born on December 8, 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico. His twin died at the age of two, and the family moved to Mexico City shortly thereafter. Rivera began his formal art training at the age of 12 at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. Rivera completed his studies in 1905, and the following year, he exhibited more than two dozen paintings at the annual San Carlos Academy art show. One of his works from this time, “La Era,” or “The Threshing,” displays elements of Impressionism in the play of light and shadow and the artist’s distinctive use of color.

He later moved to Europe, where he spent over a decade studying in Spain and France. Rivera’s artistic journey began in Madrid, where he studied Realism and Impressionism under painter Eduardo Chicharro Aguera. At the Prado Museum, he was deeply influenced by Spanish masters like El Greco, Goya, and Velazquez. During this period, he created works such as “Night Scene in Avila,” which blended elements of Realism and Impressionism.

Night Scene in Avila. Diego Rivera, 1907 Cr. Wikiart

He then moved to Paris, a hub for avant-garde artists. Here, he showed six paintings at the 1910 Société des Artistes Indépendants exhibit. Works from this time, including “Breton Girl” and “House Over the Bridge,” reveal an Impressionistic focus on light.

Upon returning to Paris, Rivera’s style shifted dramatically toward Cubism, then at its height. Under the influence of Pablo Picasso and Paul Cezanne, his work became more abstract. His 1912 “View of Toledo” combined recognizable buildings with Cubist elements, while his 1913 “Portrait of Oscar Miestchaninoff” fully embraced the Cubist style, showcasing the use of geometric forms and intersecting planes to portray multiple dimensions of a subject.

movement. This government-sponsored initiative aimed to create art that was accessible to the public and celebrated Mexico’s history, culture, and revolutionary ideals. Rivera’s murals often depicted scenes from Mexico’s past, focusing on indigenous life, the Mexican Revolution, and the struggles of the working class. His art was a tool for social change, celebrating Mexican identity and critiquing capitalism and foreign influence.

For his first mural, Creation, painted on a wall in the National Preparatory School auditorium in Mexico City, Rivera depicted a heavenly host with Renaissance-style halos. The mural was completed in 1922 and was one of Rivera’s earliest works commissioned by the Mexican government to help define a new national art.

In 1922, Rivera joined the Mexican Communist Party and founded the Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters and Sculptors. He then began a massive series of frescoes at the Secretariat of Public Education building in Mexico City. Titled “Ballad of the Proletarian Revolution,” the project focused on Mexican society and its revolutionary history. He would not complete the finished work—which consists of over 120 frescoes covering more than 5,200 square feet—until 1928.

You can read and see some of these frescoes HERE in an article by Megan Flattley. These are photos from her article:

Literacy (above left), a key fresco in the series, reflects the central role of education in post-revolutionary Mexico. The scene depicts a teacher giving out books to revolutionary soldiers, who are shown learning to read. This imagery not only highlights the national campaigns to spread education across the country, but it also directly relates to the function of the Secretariat of Public Education building where the mural is located.

This is another painting from this time. Not sure if it was part of another mural or stood alone:

Between 1929 and 1935, Diego Rivera painted a monumental mural entitles “The History of Mexico” on the main staircase walls of the National Palace in Mexico City.

This incredible mural is divided into three distinct sections, each depicting a different historical period:

The south wall, titled “Mexico Today and Tomorrow,” portrays a vision of a socialist future for Mexico, featuring images of workers, peasants, and a portrait of his wife, Frida Kahlo, alongside Karl Marx. The north wall depicts the ancient Aztec world, showcasing their vibrant culture, daily life, and mythology. The central, largest wall, titled “From the Conquest to 1930,” illustrates Mexico’s tumultuous history as a series of conflicts, from the Spanish conquest and colonial rule to its struggle for independence and the Mexican Revolution.

In case you are wondering that is Frida in his painting! Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera met when she was a young art student and he was already a celebrated muralist. She first approached him at the National Preparatory School in 1927, seeking his professional opinion on her work. He was immediately struck by her talent and unique personality. They began a relationship despite their significant age difference—she was 22 and he was 42—and married in 1929.

Their tumultuous marriage was defined by passionate love, constant infidelities from both sides, and intense artistic collaboration. They were deeply influential to each other’s work and political beliefs, sharing a commitment to Communism and a deep pride in Mexican identity. They divorced in 1939, but their separation was short-lived, as they remarried a year later. Their second marriage, though still filled with complexities and challenges, lasted until Frida’s death in 1954. Their relationship remains one of the most famous and complex in art history.

This video made me cry… they shared so much… love!

After his fame grew in North America, Diego Rivera was brought to San Francisco by architect Timothy Pflueger in 1930, coinciding with his first major U.S. exhibition. During his time there, Rivera completed three major murals: The Allegory of California, which depicts a female figure symbolizing the state and its workers; The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City, a meta-mural that illustrates the process of creating a fresco; and the epic five-fresco work, Pan American Unity, which celebrates the coming together of North and South American cultures.

There is Frida again! ^ ^

Arts. There, Rivera created the “Detroit Industry Murals,” a series of 27 panels that he considered one of his most successful projects. Completed in 1933 with the help of assistants, the murals depict the evolution of the Ford Motor Company and the industrial power of Detroit.

In 1933, Diego Rivera was commissioned by the Rockefeller family to paint a large mural for the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center in New York City. The mural, titled Man at the Crossroads, was intended to depict the crossroads of industry, science, and socialism. However, the commission became a major point of conflict when Rivera included a clear portrait of Vladimir Lenin among the figures. Despite the Rockefellers’ request to remove or alter the portrait, Rivera refused, leading to the mural’s destruction. This incident became a famous symbol of the clash between art and political ideology and cemented Rivera’s reputation as an uncompromising artist dedicated to his revolutionary beliefs.

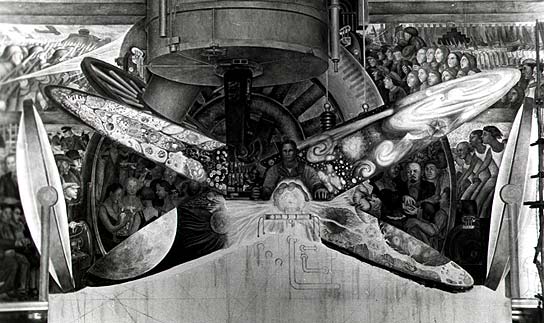

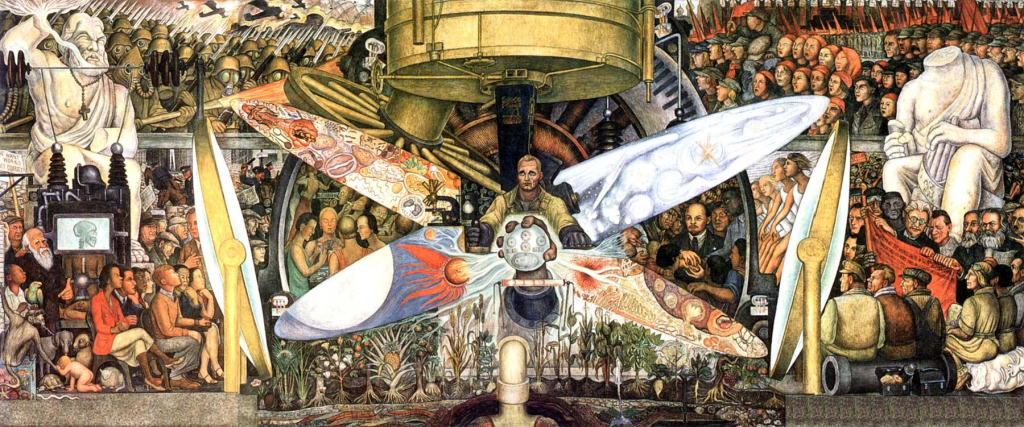

Fortunately, Diego took photos of the mural before it was destroyed:

Rivera used the photos to recreate the mural in Mexico titled Man, Controller of the Universe located at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes. In it a central worker operates a powerful machine. This figure stands at the crossroads of the era’s dominant political ideologies: capitalism is represented on his right, while communism is on his left. This arrangement reflects Rivera’s Marxist belief that humanity, through labor and technology, has the power to shape its own destiny.

A current theme in his paintings were the flower sellers. It is believed that the dominance of flowers often represents the upper class’s control over the poor. The vendors, who represent the poorest classes, are shown bowing in submission, serving those with the wealth to purchase these luxury items. These are from 1942:

Diego Rivera’s influence on Mexican art is immense; he remained a central force in shaping a national artistic identity throughout his life. But his legacy went beyond Mexico’s borders, he had a profound impact on the conception and purpose of public art worldwide.

In the US, by painting monumental scenes of American life on public buildings, Rivera provided the direct inspiration for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) program, which would go on to employ thousands of artists across the nation.

His murals, with their powerful social and political themes, served as a model for artists in Latin America who sought to create a national art form centered on social justice and indigenous history. He also impacted artists in Europe, particularly those involved in left-wing art movements, by demonstrating how large-scale public art could be used as a tool for political education and social transformation.

Jose Clemente Orozco

José Clemente Orozco is born on November 23 of 1883 in Zapotlan el Grande, Mexico, to Ireneo Orozco, a businessman, and Maria Rosa, a homemaker and amateur singer. A few years later, the family moves to Mexico City, where he takes night classes at the famed San Carlos Academy of Art.

In 1904, José Clemente Orozco lost his left hand in an accident while mixing chemicals to make fireworks for Mexican Independence Day. The resulting explosion severely injured his hand and eye. Because the holiday delayed his medical treatment, gangrene set in. To save his life, his hand and wrist had to be amputated.

This experience deeply affected him and contributed to the sense of torment and angst in his art. After the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, worked as a political cartoonist, satirizing both sides of the conflict.

He was a fervent supporter of the Mexican Muralism movement, which aimed to make art accessible to the public and to tell the story of Mexico’s history. While he shared this goal with Rivera and Siqueiros, his style and themes were distinctly different. His murals rarely depicted romanticized views of Mexican history. Instead, they focused on the brutal realities of war, the exploitation of the poor, and the universal suffering of humanity.

In 1916, José Clemente Orozco held his first solo exhibition, “The House of Tears,” which featured paintings of Mexico City’s red-light district. The work was largely ignored or harshly criticized by art critics.

In search of better opportunities, José Clemente Orozco traveled to the United States. At the Texas border, customs officials destroyed two-thirds of his early work, judging it to be “immoral.” He went on to live in San Francisco and New York City, where he earned a living by painting cinema posters and Kewpie dolls.

In 1923, Mexico’s new revolutionary government launched an ambitious campaign to promote national identity and literacy through public art. As part of this initiative, they hired muralists, including José Clemente Orozco, to paint murals on public buildings. Orozco began his first mural cycle at the National Preparatory School at San Ildefonso College, where he sought to depict the raw and often brutal reality of the Mexican Revolution. However, his unromantic and visceral style was met with hostility from the students, who rejected his dark themes and defaced his murals. This conflict forced Orozco to abandon the project and leave the school.

Despite this initial setback, Orozco later returned to the school on 1926 and completed the massive, three-story mural cycle. Over the course of several years, he created some of his most iconic works, including The Trench, a powerful and chaotic depiction of the revolution’s brutality, and The Franciscan and the Indian, which critiques colonial history. Upon their completion, the murals received widespread critical acclaim, cementing Orozco’s reputation as a master muralist and a key figure of the movement.

This is the Franciscan and the Indian:

The mural depicts a Franciscan friar in a dark, imposing robe, standing over a kneeling, almost naked indigenous figure. The friar’s gesture is ambiguous; while he may be offering a gesture of salvation or instruction, his large, looming form suggests a paternalistic and dominating presence. The indigenous figure, meanwhile, is shown in a state of subjugation and vulnerability. To me the indigenous head looks like it’s suffocating.

In 1930, José Clemente Orozco was commissioned by Pomona College in Claremont, California, to paint a mural in the student cafeteria. For this project, he created Prometheus, a monumental work depicting the mythological titan stealing fire from the gods to give to humanity. The mural was not only a powerful symbol of rebellion and enlightenment but also a landmark achievement, as it is widely considered the first true fresco ever painted in the United States. With its dramatic, muscular figures and dynamic energy, the work introduced the raw, expressive style of Mexican muralism to a new American audience.

This mural depicts the Greek mythological figure of Prometheus, a titan who stole fire from the gods to give to humanity. Orozco uses this myth as a symbol for humanity’s struggle and rebellion against oppressive forces.

The following year, Orozco was commissioned to paint another mural cycle, this time for the New School for Social Research in New York. These murals, collectively known as The Mexican Revolution and Universal Brotherhood, continued his exploration of social and political themes. The frescoes address the struggles of the working class and the promise of a more equitable society.

Between 1932-1934, José Clemente Orozco travels northeast to paint his incredible The Epic of American Civilization at the Baker Library in Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. This mural is made up of the 24 panels that cover nearly 3,200 square feet of wall space.

According to the website of the Baker library, now the Hood Museum: “José Clemente Orozco reorients the ‘epic of America’ from the standard US narrative that begins with British colonization along the northeastern seaboard and proceeds heroically west to a Mexican story rooted in Mesoamerican civilizations and the devastation wrought by the Spanish Conquest . . . Orozco presents America’s epic as cyclical in nature, the eternal return of destruction and creation, rather than a linear tale of democratic expansion and progress.”

This last image was the one that impressed me the most and when I read about its meaning I was even more impressed that this college was well … to put it in plain words… OK with it. Here is a description of its meaning:

The image is a searing condemnation of institutions that Orozco saw as lifeless and detached from human experience. The skeleton, dressed in academic robes and a graduation cap, represents academia, while the other skeletal figures in the background symbolize the church and intellectual elites.

By showing these institutions “giving birth” to another skeleton, Orozco is conveying that they produce only death, spiritual decay, and sterile ideas, rather than new life or genuine knowledge. He believed that formal education and religious dogma were not helping humanity but were instead part of a corrupt, lifeless system that perpetuated oppression and intellectual emptiness. The skeleton giving birth is a grotesque and direct metaphor for Orozco’s belief that these “modern gods” were utterly devoid of life and relevance.

Like WOW!!! And this is what it says in the website of the Museum:

The Orozco Room was made possible by the Manton Foundation, whose generosity provides perpetual support for the preservation, understanding, and awareness of the Orozco mural.

One would think… Talk about shooting yourself in the foot… right?…what?! But this is what an academic institution should provide… the opportunity to see more than one perspective.

José Clemente Orozco returned to Mexico in 1934. He then painted the mural Katharsis at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City. In this mural, Orozco presents a dystopian vision of humanity, consumed by conflict and decay. The chaotic backdrop is a frenzied scene of agitated protesters and men violently engaged in combat among piles of cogwheels, weapons, and machinery, symbolizing a world ravaged by industrialization and war. The most prominent figure is a laughing, prostituted woman who lies provocatively on her back, serving as a dark symbol of moral corruption. In the foreground, Orozco includes the grimacing, disembodied heads of other prostituted women, their faces painted with garish makeup, to emphasize humanity’s grotesque self-destruction.

From the years 1936-1939, Orozco was invited to paint at the National building of Guadalajara, Mexico. He creates an enormous mural of Miguel Hidalgo, the leader of the War of Independence of Mexico from Spain. This painting is known as “Hidalgo Incendario” that translates to Hidalgo Firestarter.

In 1939, Orozco paints The “Man of Fire” (Hombre de Fuego) part of a mural at the Hospicio Cabañas. The mural depicts a man engulfed in flames ascending into the building’s central cupola. It is considered by many Orozco’s masterpiece.

The central figure is a man consumed by fire, suspended in a swirling, chaotic void. The most common interpretation identifies him as Prometheus, the Greek mythological titan who stole fire from the gods to give to humanity. The fire represents knowledge, enlightenment, and civilization, while Prometheus’s sacrifice and punishment symbolize the painful process of human progress and rebellion against destiny.

However, the mural also connects to indigenous Mexican mythology, particularly the myth of Quetzalcoatl, who was associated with fire and was said to have created humanity from bones and his own blood. This dual symbolism allows Orozco to bridge Western and indigenous traditions, making the work a profound statement on the universal cycle of creation and destruction.

Orozco’s genius is in his use of the dome’s complex architecture that forces viewers to look up into the vortex of color and light.

Orozco continued painting on and off until 1949. He died of heart failure at the age of 65 while painting a public housing mural.

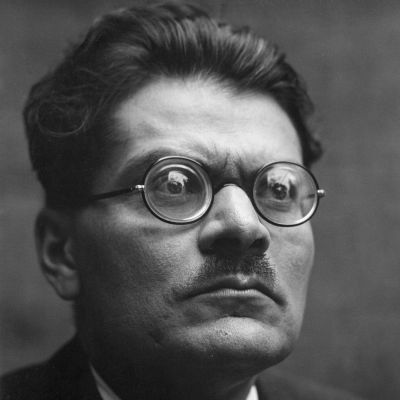

David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Alfaro Siqueiros was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, in 1896, but his family life was tumultuous. After his mother died when he was four, his father, a lawyer, sent him to live with his grandparents. This upbringing, marked by early separation from his immediate family, fostered a restless spirit in him. When he was a teenager, he moved to Mexico City and began his formal artistic training, first at the National Preparatory School and later at the Academy of San Carlos.

His interest in art quickly became inseparable from his developing political consciousness. At just 15 years old, he became a leader in a 1911 student strike at the Academy of San Carlos, protesting the school’s old-fashioned teaching methods.

At just sixteen years old in 1914, David Alfaro Siqueiros enlisted in the Constitutionalist Army to fight in the Mexican Revolution. This experience proved to be a pivotal moment for him, leading to his discovery of “the working masses—the laborers, peasants, artisans, and the indigenous… (and above all), the enormous cultural traditions of our country, particularly with respect to the extraordinary pre-Columbian civilizations.” His time in Europe, where he traveled in 1919 and spent three years, was equally influential. The combination of these two experiences shaped his artistic philosophy, which he solidified in a manifesto published in the magazine Vida Americana in Barcelona in May 1921.

Siqueiros’s relationship with the Mexican government soon deteriorated. His deep-seated commitment to the Mexican Communist Party that he joined upon his return from Europe in 1922, his decisive role in founding the artists’ union and its newspaper (El Machete), and his increasingly vocal opposition to official government policy led to him losing all his commissions after 1924. The following year, he decided to abandon his artistic career to focus exclusively on political activities.

Siqueiros would restart his artistic career in the 1930s, but his ideological militancy remained the central force in his life. In 1930, after spending several months in jail for his role in a May Day protest, he was sentenced to internal exile in Taxco. In 1936, he again went to war, fighting for the Republican army in the Spanish Civil War. At the beginning of World War II, he was exiled to Chile from 1940 to 1944 for his alleged involvement in the assassination of Leon Trotsky, and in 1960, he was jailed again on charges of promoting “social dissolution.” When he was released from prison four years later, he carried with him the ideas for what would become his final masterpiece: The March of Humanity on Earth and Toward the Cosmos.

David Alfaro Siqueiros’ Painting Philosophy

Siqueiros firmly believed that monumental public art could not be created by a solitary genius. Instead, he championed a collective, collaborative approach, which he considered a revolutionary, democratic, and modern method of artistic production.

Siqueiros’s philosophy was a direct extension of his communist ideology. He viewed the creation of large-scale murals as a process similar to an industrial or social project. He believed that for art to be truly for the people, it should be created by a team of people.

To implement this vision, he established a structured workshop, or “mural team,” where he would serve as the director. This team included:

Artists and Assistants: Painters who helped execute the vision on the monumental scale required.

Technicians and Engineers: Experts who helped him experiment with modern industrial materials, tools like spray guns, and new painting techniques.

Writers and Researchers: Specialists who provided the ideological and historical context for the murals’ themes.

These are some of his incredible murals:

Between 1923 and 1924, Siqueiros creates his first murals at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. Among them are the Spirit of the West and the Burial of a Sacrificed Worker (1923-1924). In the latter, the “sacrificed worker” is not an individual but a symbol of the proletariat.

In 1932, David Alfaro Siqueiros painted the mural America Tropical on the roof of a museum in Los Angeles. This mural caused quite a scandal. Siqueiros’s original vision was a beautiful, tropical scene, but he secretly painted a crucified indigenous man under a symbol of American imperialism. The mural was immediately whitewashed but has since been restored.

Here is a sequence of photos from the moment he painted it to the final restoration:

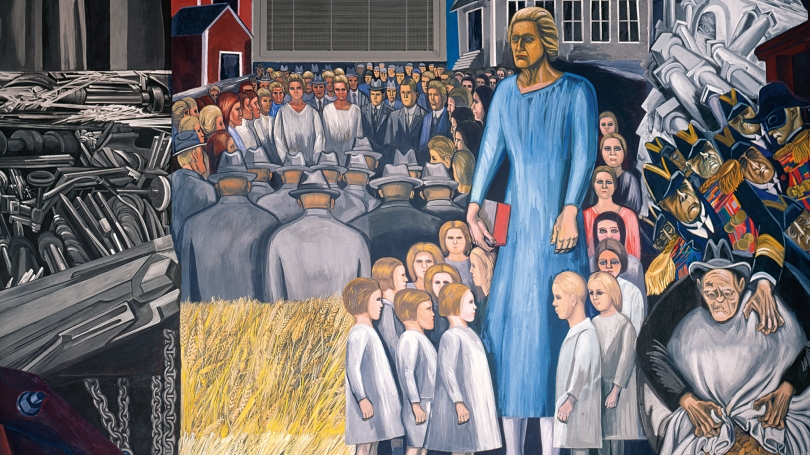

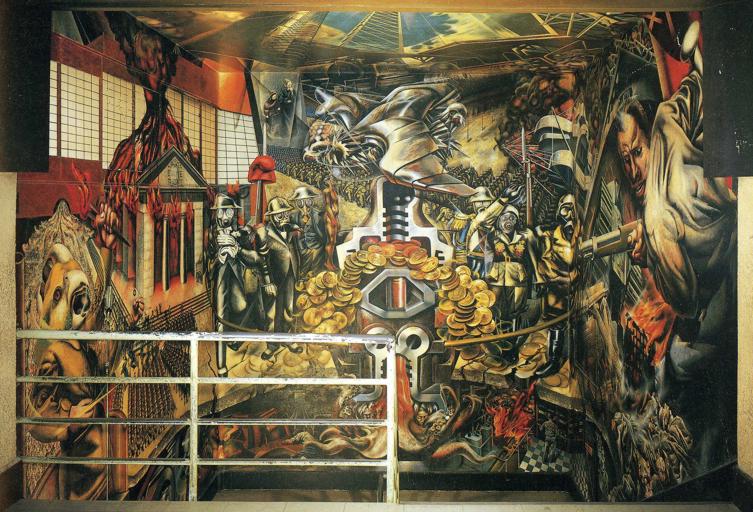

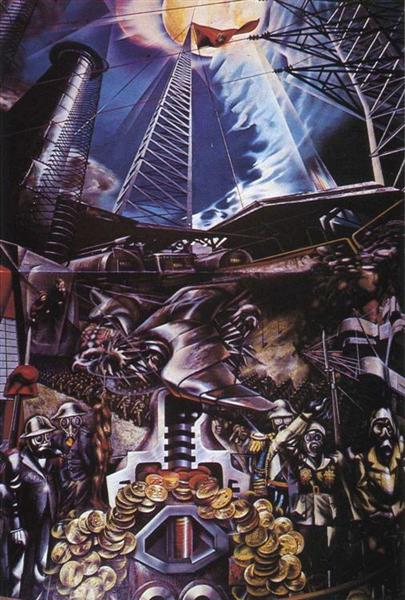

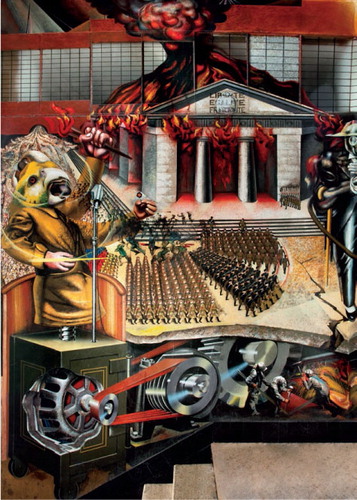

Between 1939 and 1940, Siqueiros created Portrait of the Bourgeoisie. It is a monumental mura llocated in the stairwell of the Mexican Electricians’ Union headquarters in Mexico City. The mural is a powerful and biting critique of capitalism, depicting a chaotic and destructive world driven by greed and technology.

Details of the mural.

From 1940 to 1944 Siqueiros is exiled to Chile for his alleged involvement in the assassination of Leon Trotsky. When he returns to Mexico he paints La Nueva Democracia, New Democracy in 1944. In this mural the powerful female figure in the mural is a personification of the new democracy itself. Her exposed, prominent breasts are not a sexual element but a deliberate universal symbol of motherhood and creation to represent a new, productive, and fertile society being born out of revolution and conflict. She is a metaphor for the new life and hope that will emerge from the ashes of oppression, with her body representing the very lifeblood of the new nation.

During his second and last imprisonment, he develops the ideas for what would become his final masterpiece: The March of Humanity in Latin America and Toward the Cosmos. This mural became the biggest mural in the world as it covered 12 sides of a building with almost 94,000 feet of mural!

The building is called El Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros. The creation of the Polyforum and its central mural, The March of Humanity in Latin America, was a truly collective and international undertaking, reflecting Siqueiros’s philosophy on team painting. To manage the project’s immense scale, he assembled a large and diverse group of architects, engineers, painters, sculptors, and acoustics experts. The team was composed of artists and technicians from all around the world, including members from Japan, Italy, United States and Argentina, among other countries. Siqueiros purchased an additional piece of land next to his home in Cuernavaca to serve as a dedicated workshop where the team could complete all of the mural’s panels.

Work on the project began in 1964 and was officially inaugurated on December 15, 1971.

I found this incredible video of him creating it. My jaw dropped like 13 floors below my feet. I’m so glad it exists.

I was trying to see if his mural is still among the biggest in the world. And it is not according to most sites… and they don’t even list it even though it should be! … And when you see the quality of what is listed, I’m sorry to those artists but they have much to learn from this man, not only in the painting but in the concept and meaning behind his paintings! NOT EVEN CLOSE!

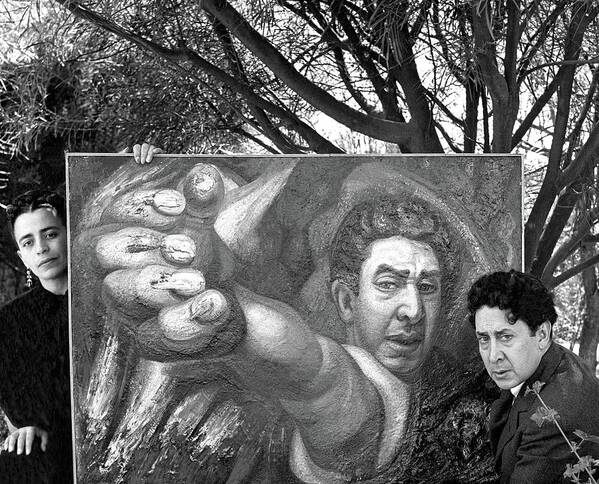

Last I wanted to highlight the fact that there was person that was by his side for 40 years, Ángelica Arenal de Siqueiros! His wife! She was a key figure in his life and work, acting as his “integral secretary,” collaborator, cultural manager, and a model for several of his most important murals. Her participation was fundamental to Siqueiros’s artistic production, as she supported him in his projects and accompanied him in his political struggles. This included her role as a correspondent during the Spanish Civil War and her active life at his side for forty years.

Role as a Manager and Collaborator:

Arenal was instrumental in supporting Siqueiros’s prolific career. As his comprehensive assistant, she managed the day-to-day logistics of his life and work, including typing his books from dictation, organizing his appointments, and handling the complex logistics of his massive mural projects. As a cultural manager, she was vital in promoting his work and ensuring it was seen not just as art, but as a platform for political struggle and freedom. Her deep commitment to these ideals was evident in her role as a correspondent during the Spanish Civil War, where she actively supported the revolutionary cause.

Figure in Siqueiros’ Artwork

Beyond her organizational roles, Arenal was a constant source of inspiration and a central figure in Siqueiros’s own work. She modeled for several of her husband’s paintings, representing key figures in murals such as The Dawn of Mexico and the “Women Claiming Their Rights” segment of the mural For a Comprehensive Social Security for All Mexicans. She was also the subject of a powerful portrait painted by Siqueiros in 1947 and inspired his 1950 mural Omen. Her presence in his art is a testament to their deep professional and personal partnership.

What a beautiful partnership!

I hope that you’ve enjoyed learning about these incredible painters of Mexico. When will the world live such genius in one place and time like that again?! ¡Viva Mexico!