4,000-2,000 BCE to 500 CE

Hunter-gatherers left their mark in the land that is now part of the country Rwanda during the Stone and Iron Ages. These early inhabitants were the ancestors of the Twa, aboriginal pygmy hunter-gatherers who remain in Rwanda today. Their nomadic lifestyle, focused on finding food and shelter, laid the groundwork for the arrival of the Bantu peoples. These agriculturalists brought with them a more settled way of life, forming communities and laying the foundation for Rwanda’s future social structure.

Over time, these communities coalesced into clans, bound by shared ancestry and traditions. These clans provided a sense of belonging and security for their members. As Rwandan society grew more complex, the clans gradually gave way to the rise of powerful kingdoms. These kingdoms, often competing for resources and influence, became the dominant political force in the region.

1081 CE

One such kingdom, led by the ambitious King Gihanga Ngomijana was established in Rwanda in 1081 CE. He was the son of a blacksmith and woodwork expert called Kazi. Through strategic alliances and military conquests, King Gihanga managed to incorporate several neighboring territories into his domain. This act of unification marked a pivotal moment in Rwandan history, paving the way for the establishment of the First or Original Kingdom of Rwanda which he reigned until 1114.

Of what I read online he was from the Hutu people.

Predominant colonial-influenced oral accounts set the reign of Gihanga and the establishment of the Kingdom of Rwanda in the 11th century but modern researchers and scholars dispute this account as the interpretation of Gihanga’s deeds and qualities match characteristics of kings that lived during the bronze age.

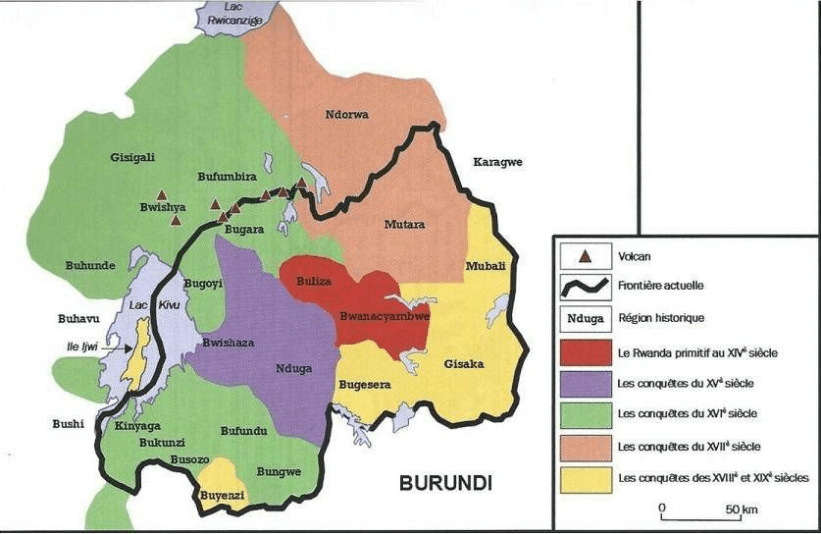

The Kingdom of Rwanda before the scramble of Africa. After 1885, Rwanda lost about half her original size. A big part went to what is now Uganda, and Burundi.

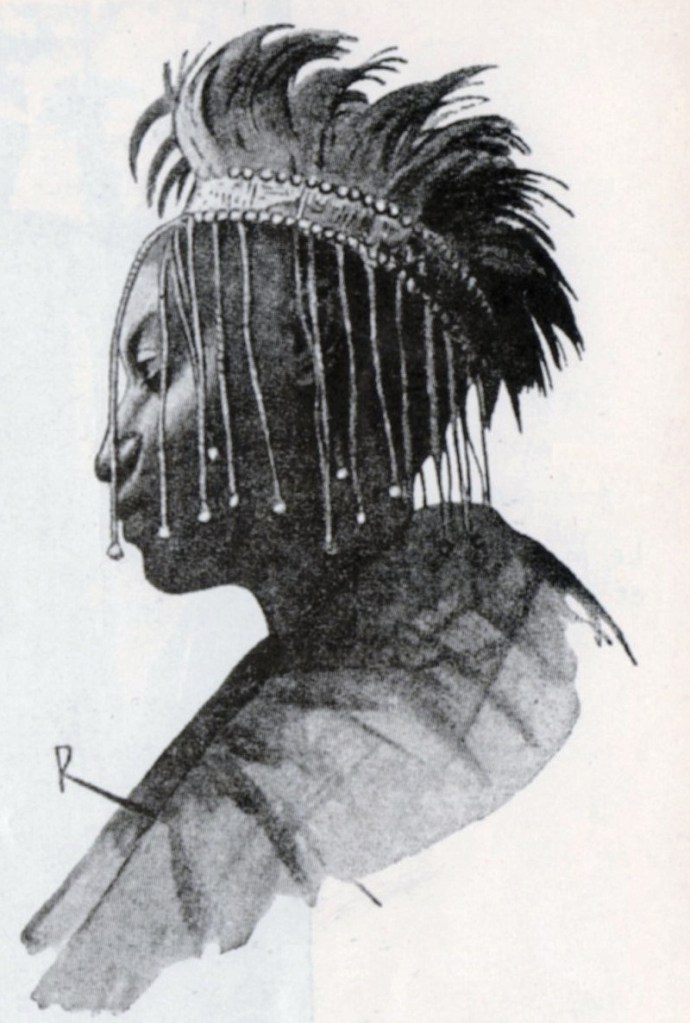

King Gihanga Ngomijana. This is the only illustration I found of him online. Cr. Wikimedia Commons, Idzubamithra

1300 -1600 CE

The Tutsi, a pastoral people, established dominance over the Hutu, who were agriculturalists. According to tradition, Ruganzu I Bwimba, a Tutsi leader, founded a kingdom in the Bwanacambwe region near Kigali in the 15th or 16th century. What is now central Rwanda was absorbed in the 16th century, and outlying Hutu communities were subdued by the Tutsi mwami (“king”) Ruganzu II Ndori in the 17th century.

During his reign, King Ruganzu II Ndori ( 1560’s – 1600’s?) conquered many territories and expanded his Kingdom. He was a great warrior and was alleged to have performed miracles. His life and reign pervade many legends in the history of Rwanda. He revolutionized his troops and terrified his neighbors. His favorite troops were given the name of Ibisumizi, those who are not scared to attack. Under his reign, he never lost any battle. s the most renowned king of Rwanda.

Monument built in King Ruganzu II Ndori’s honor at Kirenga Cultural Center. Cr. Wikimedia Commons, Inezac.

1800

Tutsi King Kigeri Rwabugiri is another notable king of Rwanda and known as “The Expansionist”. Rwabugiri established a royal court that collected labor dues and claimed tributary food in Rubengera around 1870. This served the purpose of channeling food across the country and becoming a center of commerce.

He establishes a unified state with a centralized military structure. Ethnicity became an important factor during the period of state expansion that began in the late 19th century. Rwabugiri gained increasing control over land, cattle, and people in Central Africa. Rwabugiri not only saw a personal increase in power over the land, but also consolidated power among political elites that became known either officially or informally as Tutsi.

His expansion wasn’t just about land and cattle; he solidified the control of Rwanda among the Tutsi elite. While some conquered Hutu groups initially coexisted peacefully, resistance to Tutsi rule flared. Rwabugiri’s brutal response transformed the dynamic from commerce to violent conflict.

1858

British explorer Hanning Speke is the first European to visit the area.

1840?-1895

Kigeli IV Rwabugiri (1840? – September 1895) was the king (mwami) of the Kingdom of Rwanda in the mid-nineteenth century. He was among the last Nyiginya kings in a ruling dynasty that had traced their lineage back four centuries to Gihanga, the first ‘historical’ king of Rwanda whose exploits are celebrated in oral chronicles. He was a Tutsi with the birth name Sezisoni Rwabugiri.

He was the first king in Rwanda’s history to come into contact with Europeans when Rwanda became a German protectorate and part of its German East Africa. The Germans did not significantly alter the social structure of the country, but exerted influence by supporting the king and the existing hierarchy, and delegating power to local chiefs. Mwami Mwami Kigeri IV Rwabugiri takes the opportunity to equip his armies with guns obtained from Germans prohibiting other foreigners including Arabs from entering his Kingdom. He defends the borders of The Rwanda Kingdom fiercely against invading neighboring kingdoms, slave traders and other Europeans.

Portrait of Mwami Kigeri IV Rwabugiri. Anonymous. Cr. Wikipedia Commons.

Diadem of Kigeli IV Rwabugiri. Cr. Wikipedia Commons

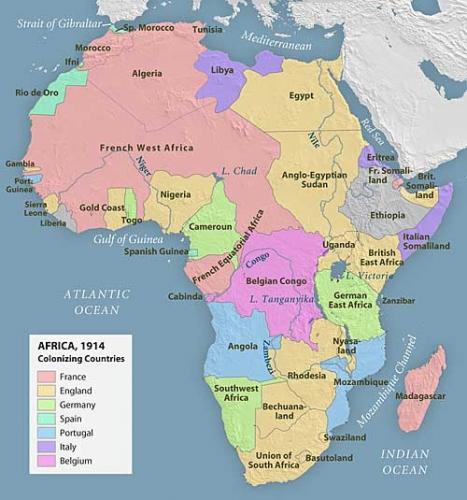

This map shows the Partition of Africa in 1914:

1916

Rwanda is occupied by Belgium forces following World War I in 1916. The Treaty of Versailles in the aftermath of World War I divided the German colonial empire among the Allied nations. German East Africa was partitioned, with Tanganyika allocated to the British and a small area allocated to Portugal and Rwanda and then Burundi were allocated to Belgium.

1922–1946 League of Nations mandate

Belgium rules both Rwanda and Urundi as a League of Nations mandate (1922-1946) called RWanda-Urundi and started a period of more direct colonial rule. The Belgians extended and consolidated a power structure based on indigenous institutions. In practice, they developed a Tutsi ruling class to formally control a mostly Hutu population, through the system of chiefs and sub-chiefs under the overall rule of the two Mwami.

Territoires du Ruanda-Urundi 1929-1938 Cr. Wikipedia Commons,1929 Institut Cartographie Militaire/ 1938 Min. colonies? – African Studies Centre Leiden

1931-1959

Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa became King on 16 November 1931, the Belgian colonial administration having deposed his father, Yuhi V Musinga, four days earlier for alleged contact with German agents. Rudahigwa took the royal name Mutara, becoming Mutara III Rudahigwa.

He was the first Rwandan king to convert to Catholicism, converting in 1943 and taking the Christian name Charles Léon Pierre. His father had refused to convert to Christianity, and the Rwandan Catholic Church eventually perceived him as anti-Christian and as an impediment to their civilizing mission.

His reign coincided with the worst recorded period of famine in Rwanda between 1941 and 1945, which included the Ruzagayura famine (1944 – 1945), during which time 200,000 out of the nation’s population of around two million perished.

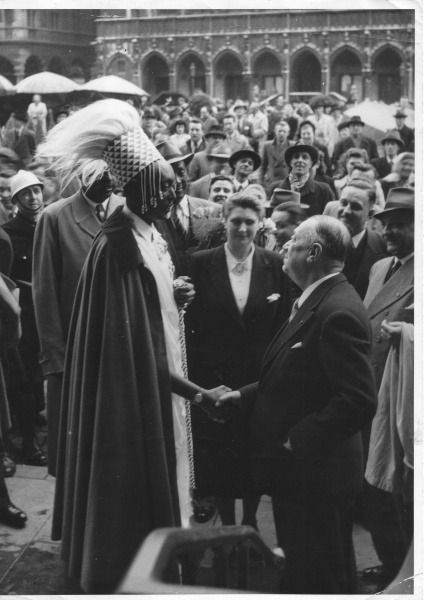

He was extremely tall at 6 ft. 9″! He was firstly married to Queen Nyiramakomali on 15 October 1933 and divorced in 1941. Later he married Queen (Umwamikazi) Rosalie Gicanda a Christian, in a church wedding on 13 January 1942.

Mwami (King) Mutara III Rudahigwa and Umwamikazi (Queen) Rosalie Gicanda.

During Rudahigwa’s reign there was a marked stratification of ethnic identity within Ruanda-Urundi, the Belgian-ruled mandate of which Rwanda formed the northern part. In 1935, the Belgian administration issued identity cards formalizing the ethnic categories, Tutsi, Hutu and Twa. After World War II, a Hutu emancipation movement began to grow throughout Ruanda-Urundi, fueled by increasing resentment of the inter-war social reforms, and also an increasing sympathy for the Hutu within the Catholic Church. Although in 1954, Rudhahigwa abolished the ubuhake system of indentured service that exploited Hutus, this had little real practical effect.

Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa visiting a Catholic Mission and below Belgium. (In 1949?) Sadly the photographs are not well captioned so they have no dates. I looked up his visit to Belgium, and it said the first one was in 1949.

United Nations trust territory, 1946–1962

The League of Nations was formally dissolved in April 1946, following its failure to prevent World War II. It was succeeded, for practical purposes, by the new United Nations (UN). In December 1946, the new body voted to end the mandate over Ruanda-Urundi and replace it with the new status of “Trust Territory”. The transition was accompanied by a promise that the Belgians would prepare the territory for independence, but the Belgians felt the area would take many decades to be ready for self-rule and wanted the process to take enough time before happening. Belgians replaced most Tutsi chiefs with Hutu and organized mid-year commune elections which returned an overwhelming Hutu majority.

Independence came largely as a result of actions elsewhere. African anti-colonial nationalism emerged in the Belgian Congo in the late 1950s and the Belgian Government became convinced they could no longer control the territory. Unrest also broke out in Ruanda where the monarchy was deposed in the Rwandan Revolution (1959–1961). Grégoire Kayibanda led the dominant and ethnically defined Party of the Hutu Emancipation Movement (Parti du Mouvement de l’Emancipation Hutu, PARMEHUTU) in Rwanda while the equivalent Union for National Progress (Union pour le Progrès national, UPRONA) in Burundi attempted to balance competing Hutu and Tutsi ethnic claims.

Rwandan King Rudahigwa died mysteriously in 1959 during a visit to Belgian authorities. Belgians offered conflicting explanations, but no autopsy was performed as his mother did not allow it. Rumors that he had been deliberately killed by the Belgian authorities were rife, and tensions rose: ordinary Rwandans gathered along routes and stoned Europeans’ cars.

Independence 1961-1962

Rwandans vote to dissolute the Tutsi monarchy in September 1961, Rwanda-Urundi became independent on 1 July 1962, broken up along traditional lines as the independent Republic of Rwanda and Kingdom of Burundi. It took two more years before the government of the two became wholly separate and two other years until the proclamation of the Republic of Burundi.

Grégoire Kayibanda presided over a Hutu republic for the next decade (1962 to 1973), imposing an autocratic rule similar to the pre-revolution feudal monarchy. He was overthrown following a coup in 1973, which brought President Juvénal Habyarimana to power.

President Juvenal Habyariman. Cr. Wikimedia Commons.

Juvénal Habyarimana founded the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) party in 1975, and promulgated a new constitution following a 1978 referendum, making the country a one-party state in which every citizen had to belong to the MRND.

At 408 inhabitants per square kilometers (1,060/sq mi), Rwanda’s population was among the highest in Africa. Rwanda’s population increased from 1.6 million in 1934 to 7.1 million in 1989 and this lack and need of land increased the crisis between the Hutus and the Tutsis.

1990-1994 Rwandan Civil War

In October 1990, Fred Rwigyema led a force of over 4,000 (Tutsi) rebels from Uganda, advancing 60 km (37 mi) into Rwanda under the banner of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Rwigyema was killed on the third day of the attack, and France and Zaire deployed forces in support of the Rwandan army, allowing them to repel the invasion. Rwigyema’s deputy, Paul Kagame, took command of the RPF forces, organizing a tactical retreat through Uganda to the Virunga Mountains, a rugged area of northern Rwanda. From there, he rearmed and reorganised the army, and carried out fundraising and recruitment from the Tutsi diaspora.

Paul Kagame. Cr. Wikimedia Commons

In the early years of Habyarimana’s regime, there was greater economic prosperity and reduced violence against Tutsis. Many hardline anti-Tutsi figures remained, including the family of the first lady Agathe Habyarimana, who were known as the akazu or clan de Madame, and the president relied on them to maintain his regime. When the RPF invaded in October 1990, Habyarimana and the hardliners exploited the fear of the population to advance an anti-Tutsi agenda which became known as Hutu Power. Tutsi were increasingly viewed with suspicion.

Following the 1992 ceasefire agreement, a number of the extremists in the Rwandan government and army began actively plotting against the president Juvénal Habyarimana , worried about the possibility of Tutsis being included in his government.

1994 Assassination of Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira and Rwandan Genocide.

On the evening of 6 April 1994, the aircraft carrying Rwandan president Juvenál Habyarimana and Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira, both Hutu, was shot down with surface-to-air missiles as their jet prepared to land in Kigali, Rwanda; both were killed. The assassination set in motion the Rwandan genocide, one of the bloodiest events of the late 20th century.

Responsibility for the plane attack is disputed, with most theories proposing as suspects either the government-aligned Hutu Power followers opposed to negotiation with the RPF and the Tutsi rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

The large-scale killing of Tutsi on the grounds of ethnicity began within a few hours of Habyarimana’s death. The crisis committee, headed by Théoneste Bagosora, took power in the country following Habyarimana’s death, and was the principal authority coordinating the genocide. Soldiers, police, and militia quickly executed key Tutsi and moderate Hutu military and political leaders who could have assumed control in the ensuing power vacuum. Checkpoints and barricades were erected to screen all holders of the national ID card of Rwanda, which contained ethnic classifications. This enabled government forces to systematically identify and kill Tutsi.

They also recruited and pressured Hutu civilians to arm themselves with machetes, clubs, blunt objects, and other weapons and encouraged them to rape, maim, and kill their Tutsi neighbors and to destroy or steal their property. Even women and children participated in this mass murder.

At the start of the killing there were more than 2,000 UN troops in Rwanda but they made no attempt to stop the bloodshed. Thye had strict rders to just monitor and not interfere. After 10 Belgian Peacekeepers were kiled the UN Force was reduced to 250. On Aril 30, the UN Security Council discussed the crisis for 8 hours but carefully avoided using the word “genocide.” They would be highly criticized for their inaction and failure to strengthen the force and mandate of the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) peacekeepers.

Although the Constitution of Rwanda states that more than 1 million people perished in the genocide, the actual number of fatalities is estimated at 800,000 Tutsis and 10,000 Twa. Between 250,000-500,000 Tutsi women were raped.

On July 4th, the RPF captured Kigali, the capital. Now it was the turn of the Hutu to flee, mostly to Zaire (now called the Democaratic Republic of the Congo.) Two weeks later, the RPF announced that the war had been won. a cease of fire was declared, and a broad-based government of national unity was formed.

Recovery 1994 – 2000

Episodes of violence continued thorughout the 1990’s, and the estimated 2 million Hutu refugees crammed into camps in neighboring countries lacked food, clean water and sanitary facilities leading to many deaths.

The government of National Unity, with Pasteur Bizimungu as president took control by July of 1994. In November of 1994, the UN Security Council set up the international criminal tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to try those accused of genocide. Over one million people (nearly one-fifth of the population remaining after the summer of 1994) were potentially culpable for a role in the genocide. The RPF pursued a policy of mass arrests for those responsible and for those persons who took part in the genocide, jailing over 100,000 people in the two years after the genocide. However the systematic destruction of the judicial system during the genocide and civil war was a major problem.

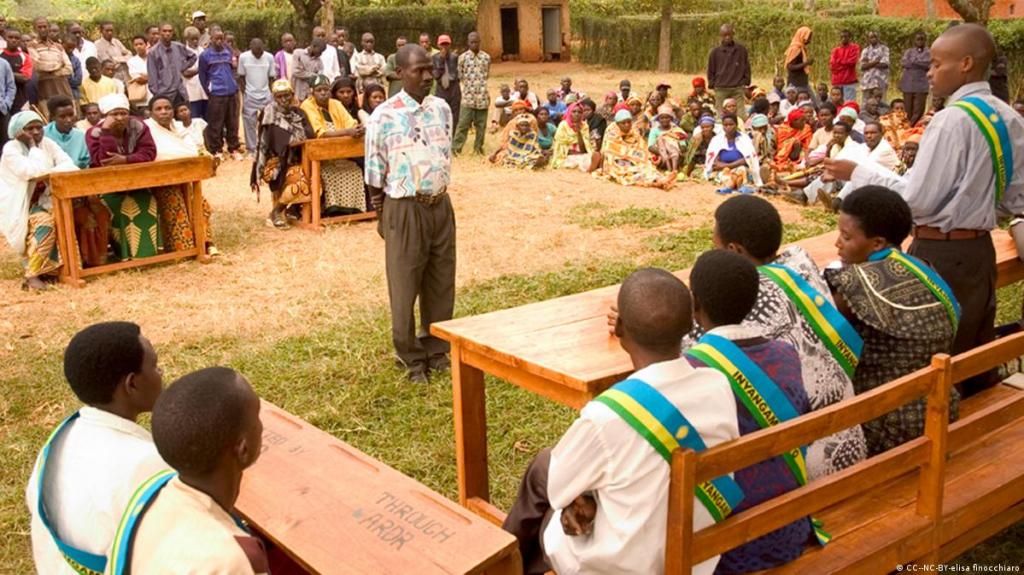

Gacaca, a traditional village court system is reintroduced. It took them up to 2012 to process all the cases! 65% of the cases had guilty verdicts. Prisoners apart from getting jail sentences also received a month of training at solidarity camps, where they learned about Rwandan history, reconciliation and justice.

In March of 2000, Bizimungu resigned , and Paul Kagame was sworn in as president. He continued Rwanda’s efforts to restore peace and stability. He directed the removal of ethnicity from Rwandan citizens’ national identity cards, and the government began a policy of downplaying the distinctions between Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa.

However his government was accused by the UN of taking part in human rights abuses by killing Hutu refugees living in the Democratic Republic of el Congo (DCR) during its own internal war between 1993 and 2003. Rwanda under his presidency has also had a difficult relationship with France. President Kagame suspended all diplomatic tries with France between 2006-2009 as it accused France of helping Hutu extremists escape from Rwanda and supporting the Hutu during the Genocide. A 2008 report by the Rwandan government-sponsored Mucyo Commission accused the French government of knowing of preparations for the genocide and helping to train Hutu militia members. In 2019, President Macron decided to reopen the issue of French involvement in the genocide by commissioning a new team to sort through the state archives.

Despite its tensions with DRC and France, Rwanda became the 54th country to join the Commonwealth. (In spite of not having any historical ties with Great Britain.). And Rwanda continues to maintain ots membership to the African union (since 1963.)

2001- to present

In 2001, new national symbols were created to reflect the story and future of Rwanda. A flag, anthem, and coat of arms were introduced as signs of hope, change and unity.

Paul Kagame is reelected in 2010 and 2017, and is the current president of Rwanda. With very strict laws outlawing divisionism and talk of ethnicities, some fear that this peace has been maintained at the cost of personal freedoms. Some believe that his government is represive.

Article 38 of the Constitution of Rwanda 2003 guarantees “the freedom of expression and freedom of access to information where it does not prejudice public order, good morals, the protection of the youth and children, the right of every citizen to honour and dignity and protection of personal and family privacy”. This has not guaranteed freedom of speech or expression given that the government has declared many forms of speech fall into the exceptions. Under these exceptions, longtime Rwandan president, Paul Kagame, asserted that any acknowledgment of the separate people was detrimental to the unification of post-Genocide Rwanda and has created numerous laws to prevent Rwandans from promoting a “genocide ideology” and “divisionism”.

The law does not explicitly define such terms, nor does it state that one’s beliefs must be spoken. For example, the law defines divisionism as “the use of any speech, written statement, or action that divides people, that is likely to spark conflicts among people, or that causes an uprising which might degenerate into strife among people based on discrimination”. Fear of the possible ramifications from breaking these laws have caused a culture of self-censorship within the population. Both civilians and the press typically avoid anything that could be construed as critical of the government/military or promoting “divisionism”.

After reading and writing about their history… I wish Rwandans unity and peace.

Sources used:

1. Wikipedia: History, Rwandan Genocide

2. Encyclopedia Britannica : History of Rwanda

3. Book: Cultures of the World: Rwanda by Cavendish Square. New York, Third Edition 2021.

4. Book: Culture and Customs of Rwanda by Julius O. Adekunle. 2007.

Muy triste la historia de Ruanda. Similar a la de muchos países de Africa.

Mucha violencia, hambre y sufrimiento. Es muy difícil asimilar y comprender esta historia y lo que queda en mente de ella es un gran caos y baño de sangre de gente inocente e indefensa. Da vergüenza que países civilizados y supuestamente democráticos hayan tenido mucho que ver en todo esto.

LikeLike

Si, es tan triste. Yo no me imagine el papel que Bélgica jugó en la historia de este país. Ni sabia que estaba involucrada como país colonizador.

LikeLike

There is no part of the Rwandan kingdom in Congo, a part of its territory are in Uganda and Burundi.

LikeLike

Thank you for letting me know Elgar! I looked into it and I will edit my post! I thought that maybe back in time it was because of a map I found, but not at all!

LikeLike