I did a search about Korean visual arts and I decided very quickly I would concentrate my research and writing efforts on this beautiful art form that comes from the heart of the Korean people during the Joseon Era.

When I was in Seoul, I visited the Seoul Arts Center and had the blessing of seeing the world’s first calligraphy museum: The Seoul Calligraphy Art Museum. There I delighted in an incredible exhibit entitled “Fantasia Joseon” and even though I did not know what it was at that time, I realize now it was all Minhwa. It was a private collector’s exhibit. So as a write I will be able to show much of this exhibit as I documented it throughly. I absolutely loved it!

This is the what the museum looked like back in 2018:

And this is only one of the museums there, the Seoul Arts Center has three other museums and a music hall!

Now let’s learn about Minhwa. Ready?

Minhwa had its origin in the Royal Court as a way to decorate palaces. These paintings were created by anonymous craftsmen who faithfully adhered to the styles, canons and genres inherited from the past. Even thought hey had no formal training, they had the training of life and travelled from place to place fulfilling commissions on the spot. They would learn the latest trends as they travelled and eventually they also started painting for the common people.

Minhwa evolved its decorative purpose into the spiritual and magical. It was used to convey messages, to protect and ward off evil spirits from their owners and their homes. Minhwa vividly portrayed the beliefs, daily life, and mythology of its time. It featured symbolic animals like tigers, dragons, and cranes, often set against colorful natural scenes with flowers, clouds, or the sun. It blended elements of Buddhism, Shamanism, Confucianism, and Taoism.

Types of Minhwa

The world of Minhwa is so vast that there are different categories. I will write about four in this post as I have many photos. This first one reminded me of one of my all time fascinations: the Cabinets of Curiosities.

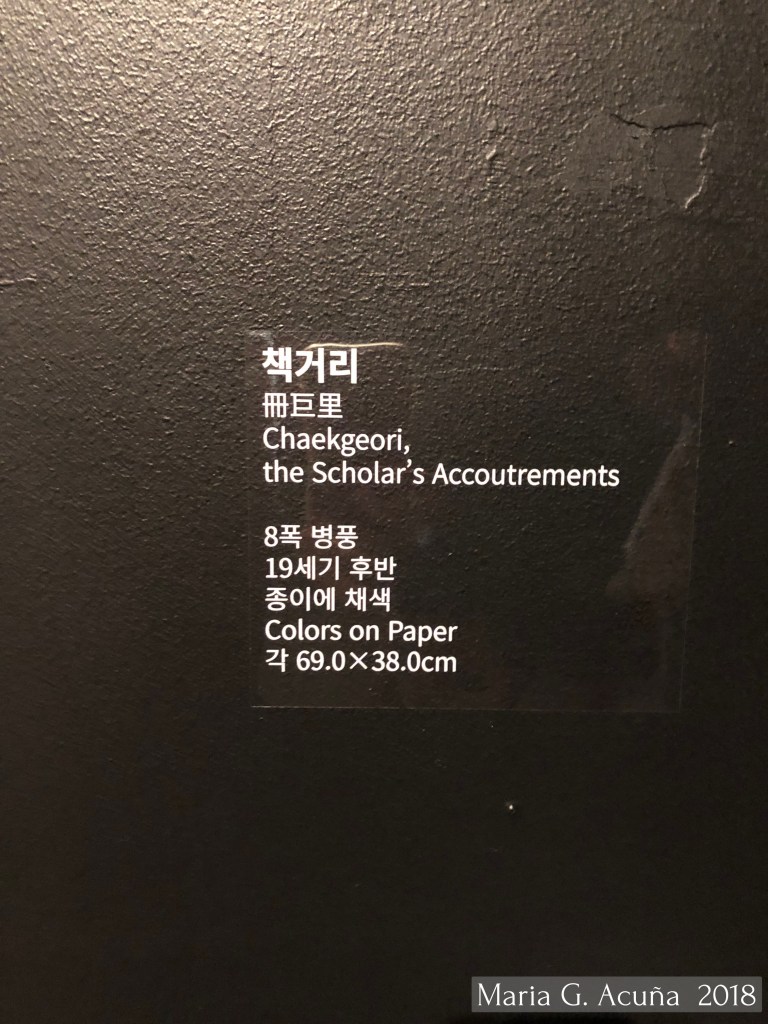

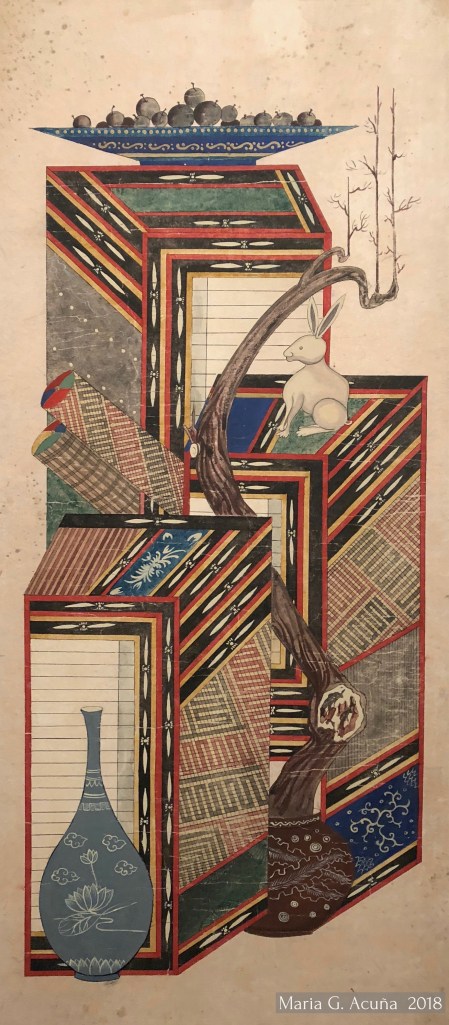

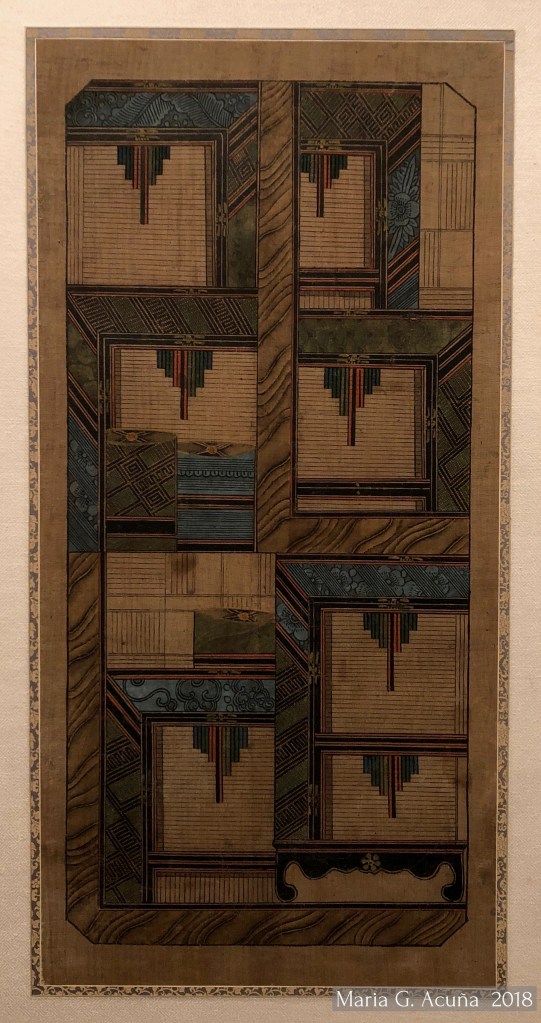

CHAEKGEORI / 책거리 (PAINTING OF BOOKS AND STATIONERY)

Chaekgeori, a genre of Korean still-life painting within the broader category of Minhwa folk art, offers a fascinating glimpse into the Joseon Dynasty’s reverence for learning and scholarly pursuits. King Jeongjo (1776–1800) of Joseon Korea, seeking to preserve traditional Confucian values in the face of encroaching foreign ideas and technologies, promoted a renewed focus on books in royal screen paintings. He encouraged court painters to feature books prominently, emphasizing their power and the importance of the knowledge they contained. Recognizing the transformative potential of books within his society, Jeongjo strategically elevated their symbolic status, positioning them as more than mere physical objects and making them accessible to artisans and other elites. Ironically, this promotion of books as symbols of intellectual and cultural capital led to an increased demand for the physical books themselves, driving up their value and making them highly prized possessions. This burgeoning desire for books, along with other material goods, initiated a significant social and cultural shift in Korea towards materialism, a trend that continues to resonate even in the twenty-first century.

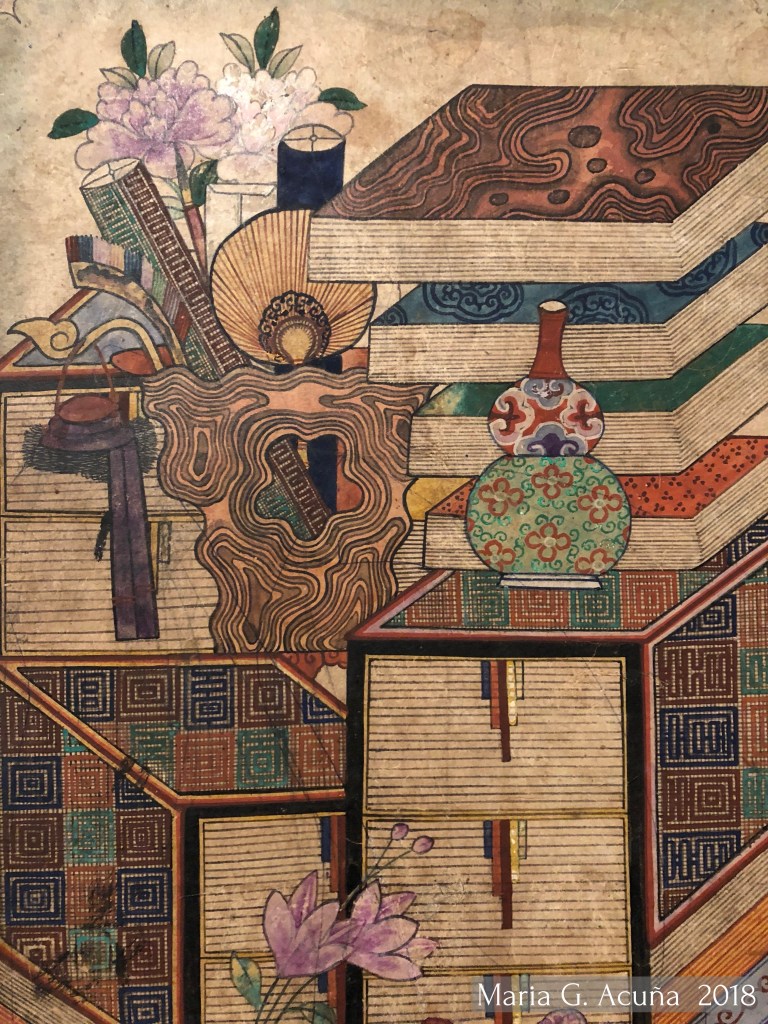

These paintings depict not just books, but a diverse array of objects symbolizing the pursuit of knowledge, wisdom, and a well-rounded life. The “Four Treasures of the Study”—paper, brush, ink stone, and ink stick—are prominently featured, naturally, but the compositions extend far beyond these essentials. Vases brimming with flowers suggest refinement and appreciation for beauty, while wine vessels hint at convivial gatherings and intellectual discourse. Arrows, fans, and eyeglasses speak to practical needs and leisure activities. The inclusion of wooden sculptures of mythical animals, musical instruments, garments, and even more flowers underscores the desire for a life enriched by culture and the arts.

Beyond these symbolic objects, Chaekgeori paintings often incorporate vibrant depictions of fruits and vegetables, each carrying its own auspicious meaning. Melons, peaches, cucumbers, pomegranates, and eggplants, among others, are included not only for their visual appeal but also as potent symbols of fertility, abundance, and longevity. This blending of scholarly symbolism with imagery representing prosperity and well-being highlights the holistic nature of the aspirations embodied by Chaekgeori.

What truly sets Chaekgeori apart within the broader landscape of Minhwa art is its distinctive visual style. The paintings often employ unusual perspectives and unconventional image ratios, creating a dynamic and engaging composition. While other forms of Minhwa may exhibit greater stylistic freedom, Chaekgeori is characterized by a high degree of technical uniformity and artistic refinement. The meticulous rendering of objects and the carefully balanced compositions speak to the skill and dedication of the artists, elevating Chaekgeori to a particularly esteemed place within Korean folk art.

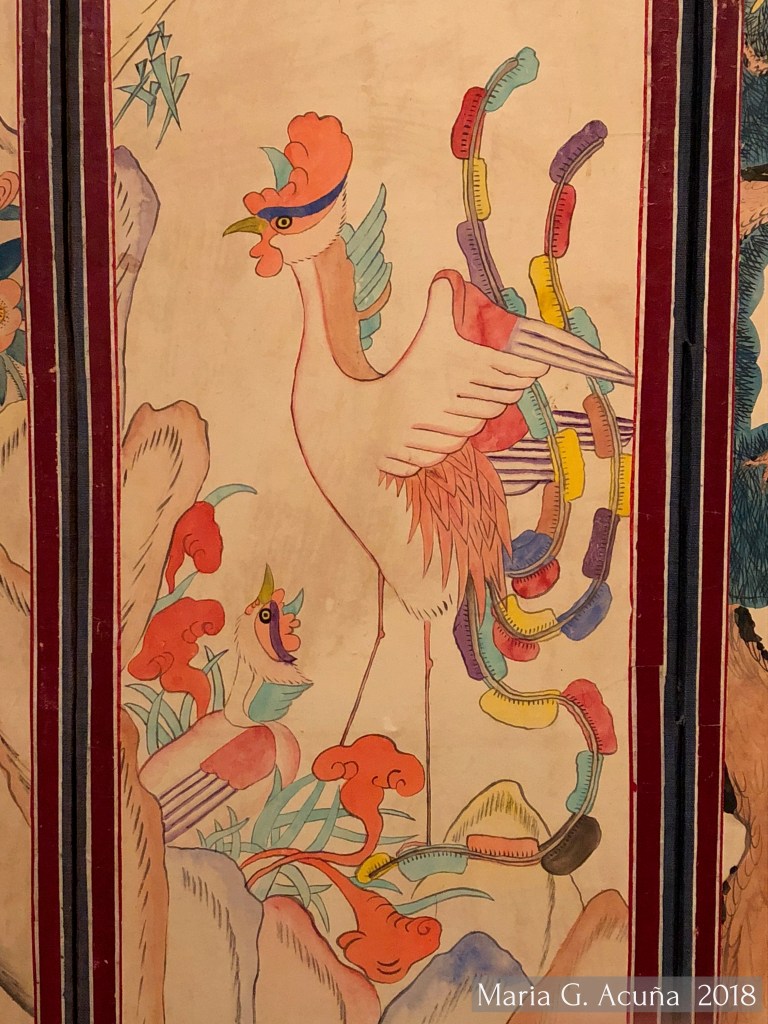

How incredible is that fantastic bird! Embodying the word Fantasia at its fullest! ^ ^

I also found these incredibles ones in the website of International Institute for asian Studies:

A striking element of this late nineteenth-century screen, is the inclusion of clouds and a dragon. The dragon here symbolizes the fervent hope for numerous sons, their education, and their subsequent rise in social standing through learning. This somewhat surreal depiction of such worldly aspirations reveals the remarkable imaginative spirit characteristic of folk-style Chaekgeori.

The following 6 panel screen, reflects clearly the influx of Chinese curiosities into upper-class Korean homes during the Chinese Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Among the books and other scholarly accoutrements—imported Chinese ceramics, brushes, paper, eyeglasses, and similar items—all vie for prominence and the viewer’s attention.

And this one from Pintarest shows winter …something us Bostonians are deeply iced in at the moment:

HWAJODO / 화조도 (PAINTING OF FLOWERS AND BIRDS)

Hwajodo, literally “flower-bird painting,” represents a beloved genre within Korean art, often gracing folding screens with vibrant depictions of the natural world. These screens are not simply botanical or zoological studies; they are rich in symbolism and convey deeper cultural meanings, particularly related to love, marriage, and fertility. A hallmark of Hwajodo screens is the frequent depiction of paired creatures. Whether it be a pair of colorful birds perched on blossoming branches, graceful deer amidst a tranquil landscape, playful rabbits frolicking in a field, or delicate butterflies flitting among flowers, the presence of paired animals is no accident. These pairings serve as potent symbols of marital harmony and happiness, representing the ideal of a loving and devoted couple. The artists carefully chose their subjects, not just for their aesthetic appeal, but also for their symbolic weight within the context of marriage.

This emphasis on the theme of a loving couple extended beyond mere sentimentality. It was deeply intertwined with the hope for fertility and the continuation of the family line. Because of this association with fecundity, Hwajodo screens were particularly favored as decorations in the bedrooms of newlyweds. Placed in this intimate setting, the paintings served as a blessing on the couple’s union, invoking the hope for children and a prosperous future.

These are a few photos I took within this style:

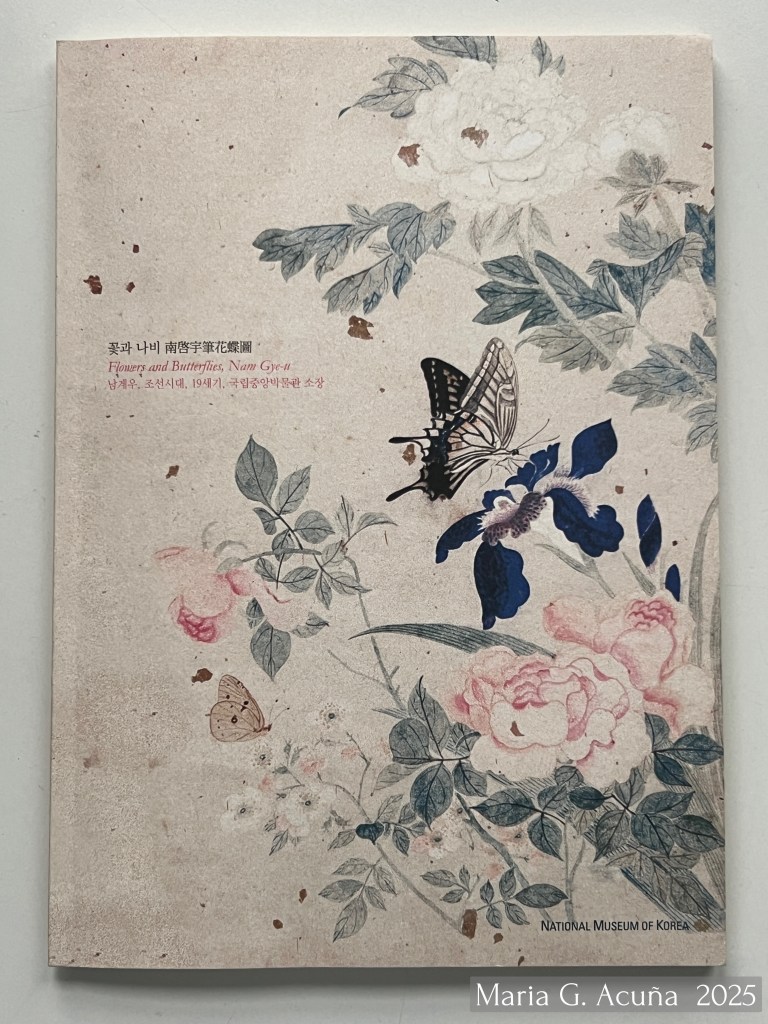

And this is the cover of book of the exhibit depicting a gorgeous Hwajodo painting!

This photo I took at the National Palace Museum. It is a detail of a screen painted during the Joseon Era:

This is what the screen looks like:

And I found these at the Museum of Korean Folk Art’s website.

And these come from the Cheong-yu Folk Minhwa Association:

Onyang Museum, late 19th century, colored paper

Cr. koreanfolkart.org

CHOCHUNGDO / 초충도 (PAINTING OF FLOWERS AND INSECTS)

Chochungdo (초충도) refers to paintings depicting plants, insects, and other small creatures. It’s an important genre in traditional Korean painting, particularly renowned for the Chochungdo works of Shin Saimdang from the Joseon Dynasty. Her delicate and beautiful depictions are highly regarded.

Characteristics of Chochungdo:

Subject Matter: Chochungdo primarily features various plants, flowers, insects, butterflies, birds, and other small animals.

Technique: They are characterized by delicate and precise depictions, often employing colors to enhance the sense of realism and vibrancy.

Meaning: Chochungdo goes beyond simply observing and depicting nature. It aims to discover the principles and lessons of life within nature and incorporate them into the paintings. They are also sometimes seen as representative of a woman’s delicate sensibilities and observational skills.

I will concentrate my photos in this category around Shin Saimdang.

Shin Saimdang’s Chochungdo:

Shin Saimdang was born on December 5, 1504. She was a Korean artist, writer, calligraphist, and poet, who lived during the Joseon period. . She was the mother of the Korean Confucian scholar Yi I. Often held up as a model of Confucian ideals, her respectful nickname was Eojin (“Wise Mother”). Her real name was Shin In-seon (신인선). Her pen names were Saim (사임), Saimdang (사임당), Inimdang (인임당), and Imsajae (임사재).

Cr. Wikimedia Commons. Unknown Artist.

During the Joseon era, married women were generally discouraged from publicly showcasing their talents. However, Shin Saimdang’s circumstances allowed her to cultivate her abilities. Having no brothers, she remained in her own home after marriage rather than moving to her husband’s family residence. Furthermore, her father carefully chose a son-in-law who would support her artistic development.

Shin Saimdang’s artwork is known for its delicate beauty; insects, flowers, butterflies, orchids, grapes, fish, and landscapes were some of her favorite themes. Approximately 40 paintings of ink and stonepaint colors remain, although it is believed that many others exist. Her Chochungdo paintings are highly valued not only for their meticulous detail but also for the deep understanding and affection for nature they convey.

A representative work of Shin Saimdang’s Chochungdo is the “Chochungdo Byeongpung” (초충도 병풍), a folding screen consisting of eight panels, each depicting different plants and insects. Click HERE to delight in this work through Google Arts & Culture.

This is perhaps her most iconic Chochungdo painting from the screen.

Watermelons and field mice by Shin Saimdang.

All elements in this painting represent prosperity. Sadly I was not able to find a photo of the original screen. Below is a detail of another of her works: grapes. Made with ink on silk.

In June 23, 2009, Shin Saimdang’s image graced the front of the 50,000 South Korean won note for the first time, the highest denomination banknote in the country. This was a significant decision, as it marked the first time a woman was featured on a South Korean banknote.

Shin Saimdang was selected because she embodies traditional Korean values and culture. She is revered as a symbol of ideal womanhood in the Joseon era, excelling not only as an artist and poet but also as a devoted mother and wife.

Featuring her on the banknote acknowledges her exceptional artistic talent and contributions to Korean art. Her paintings, particularly her Chochungdo (paintings of plants and insects), are celebrated for their delicate beauty and detailed observation of nature.

Shin Saimdang is a figure of national respect and admiration, making her a suitable representative of Korean heritage on the country’s currency.

Front: Features a portrait of Shin Saimdang, meticulously restored based on historical records.

Back: Showcases two of Korea’s significant artworks:

Shin Saimdang’s “Insects and Plants

Yi Jeong’s “Moon and Plum Blossom”. This is her son’s artwork.

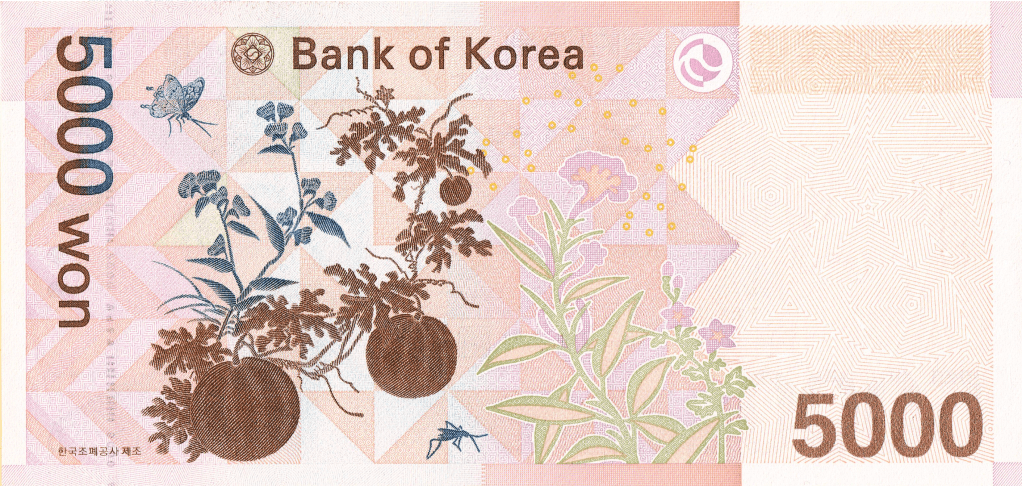

So criticism was not scarce… not only because some people thought that her traditional image reinforced the traditional gender role of women as mothers and wives, instead of highlighting their individual achievements. And adding to this, her son was featured in the 5000 bank note… a note that not only procceeded hers but that featured her work in the back!

And guess what! Looking through my leftover money from Korea I found one… with Shin Saimdang’s artwork in the back!

I wonder why couldn’t they just add his artwork to his 5000 note and her work to her note 50,000 ?

And here are some coins:

I also bought a notebook to write some of my most precious memories and it has a Chochungdo painting by Nam Gye-u. Nam was a government official and painter. He was so good at painting butterflies that his nickname became Butterfly Nam (Nam Nabi). He lived from 1811-1888.

SIPJANGSAENGDO / 십장생도 (PAINTING OF TEN SYMBOLS OF LONGEVITY)

Sipjangsaengdo (십장생도), or “Painting of Ten Symbols of Longevity,” is a traditional Korean folk painting genre that depicts ten auspicious symbols believed to represent longevity, health, and happiness. The term Jangsaeng aging slowly (or not aging at all) and living a long time (or never dying).

The precise origins of the Ten Symbols of Longevity are unclear, though it’s thought that the Chinese have long combined various longevity symbols into single images. Therefore, China is likely the ultimate source of these symbolic elements. However, the specific grouping of ten symbols found in Sipjangsaengdo appears to be unique to Korea and is not seen elsewhere in East Asia.

These Sipjangsaengdo paintings were often used for court decoration, as they were best created in a large format. Knowing the exact date when the painting of Sipjangsaengdo began is challenging as court artists rarely signed or dated their work. However, the earliest known mention of Sipjangsaengdo appears in a poem by Yi Saek (1328-1396), a Goryeo dynasty scholar and literary figure. This suggests that Sipjangsaengdo paintings were already being produced during the Goryeo period. Notably, Yi Saek’s poem mentions both the ten symbols themselves and paintings depicting them, providing the first documented evidence of this art form.

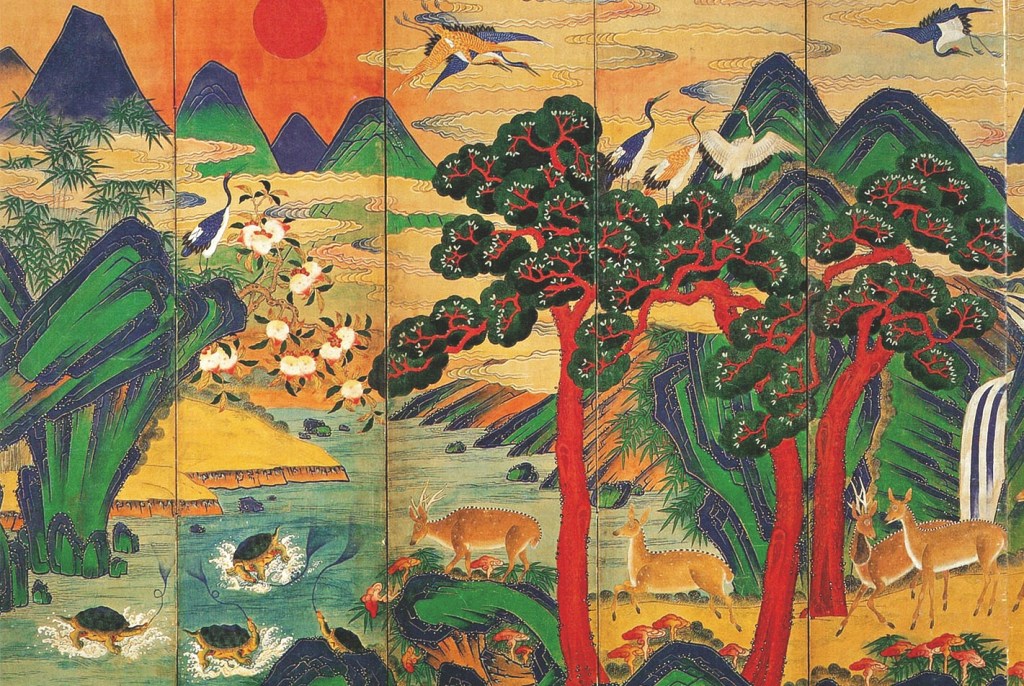

This one was housed at The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon. 1880 Color on silk.

This one was painted during the Late Joseon Period:

This is a screen I saw at the National Palace Museum:

The 10 longevity symbols are:

1. Sun (해 – Hae): Represents the source of life and energy, symbolizing eternal youth and vitality.

2. Clouds (구름 – Gureum): Symbolize peace, tranquility, and good fortune. They are often depicted alongside the sun, creating a harmonious balance. The use of clouds as a longevity motif is found only in Korea. The cloud symbolizes the realm of the immortals as espoused in Daoism, a transcendent world where the inhabitants live forever.

3. Mountains (산 – San): Represent stability, strength, and longevity. They are often depicted majestically, conveying a sense of permanence.

4. Rocks (돌 – Dol): Symbolize steadfastness, endurance, and longevity, much like mountains. Their presence emphasizes the enduring nature of life.

5. Water (물 – Mul): Represents purity, adaptability, and the flow of life. It can be depicted as a river, waterfall, or the sea.

6. Pine Trees (소나무 – Sonamu): Symbolize resilience, longevity, and unwavering spirit. They are often depicted as ancient and gnarled, signifying enduring strength. Pine trees were often depicted with Daoist immortals.

7. Bamboo (대나무 – Daenamu): Represents flexibility, resilience, and uprightness. Its hollow stem is also associated with humility. In Daoism, bamboo symbolizes the concept of Dao (“the way”), which bends without breaking like bamboo. In Confucianism, bamboo is also symbolic of humility, upright character, flexibility, and grace.

8. Cranes (학 – Hak): Symbolize longevity, grace, and purity. They are often depicted in flight, representing a connection between the earthly and heavenly realms. In folk tradition, cranes were thought to live for more than 500 years and symbolized long life.

The crane was a symbol of transcendence in Taoism and was considered a messenger that could communicate with the sky/heaven.

16.7 cm x 19.0 cm

Korea University Museum, Cr. Magazine of the National Museum of Korea.

9. Deer (사슴 – Saseum): Represent gentleness, peace, and longevity. They are often depicted in a serene natural setting. Shoulao, the Daoist God of Longevity, is often seen with a deer because deer are thought to have the ability to sniff and find the mushroom of immortality, yeongji.

H. 37.3 cm, D. 13.6 cm (mouth rim), 27.6 cm (body)

Cr. National Museum of Korea

10. Tortoises (거북 – Geobuk): Symbolize longevity, stability, and wisdom. Their slow and steady movements are associated with a long and prosperous life. The turtle is thought to be the messenger of water, just as the tiger is the messenger of the mountain.

There are other auspecious symbols of longevity like the moon, peaches and the yeongji mushroom or bullocho (불로초) (elixir grass).

According to the magazine of the National Museum of Korea, the mysterious herb of eternal youth, bullocho, 不老草 is supposed to prevent the onset of old age and disease to anyone who eats it just once. It is said to grow in the land of the immortals. According to legend, the bullocho sprouts in the east as the sun rises on the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. This herb and the mythical peach of immortality, described below, are important elements in the sinseondo, paintings of Daoist immortals.

I was curious about what this mushroom looked like and it turns out I have seen it here in Boston! It is also known as Lingzhi, and it grows at the base and stumps of deciduous trees, especially maples. And guess what we have a lot of here in New England… Maple Trees! I had no idea they could actually also look like sticks… and the video below astounded me:

I guess it tastes really bad. I don’t think I have the guts to try it! Oh well I guess I will have to be content with a mortal life! It is beautiful …with fan like caps:

Here it is in a painting from the 19th century. You can see them all over!

As the ten symbols of longevity (십장생, sipjangsaeng) grew in popularity, variations on the traditional Sipjangsaengdo (십장생도) emerged, each emphasizing specific elements and often bearing unique names. For example, Ilwolbandodo (일월반도도) focused on the sun, moon, and peaches; Haehakbandodo (해학반도도) depicted cranes and peaches against a seascape ; Gunhakdo (군학도) showcased flocks of cranes; and Gunrokdo (군록도) portrayed deer amidst pine trees. Despite these distinct titles, all such paintings, including the variations, can be broadly categorized as Jangsaengdo, longevity paintings).

It is wonderful to learn about all these symbols that I’ve seen not only on their panting but in many artifacts. Soon, I will post part two where my favorite categories are… so stay tuned!

Sources:

Wikipedia: Minhwa

The Korean Folk Art.org website. Minhwa

The Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon. This reference PDF written about was very useful.

The National Museum of Korea’s Magazine. HERE

Hola Gabi.!

Leí con cuidado tu Post sobre la pintura del pueblo coreano durante la era Joseon parte 1. Para mi es muy difícil la lectura con tantos detalles y especificaciones de una cultura tan compleja como la Coreana. Me concentre más en ver las pinturas y disfrutarlas porque son muy bellas y llenas de simbolismos.

Me llamo la atención la variedad de soportes sobre los que pintaban Desde papel de arroz, abanicos, billetes, cerámicas…etc. Así que algo nuevo aprendí de tu investigación. Gracias y hasta la próxima.

LikeLike